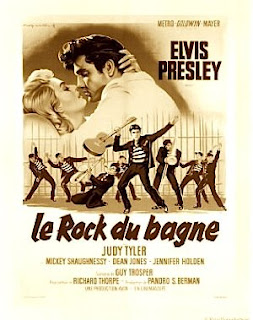

While watching Jailhouse Rock last night I realized I’d forgotten about the scene in which Elvis is flogged by order of the prison warden as a consequence of striking a guard following a food riot in the prison commissary. Presumably a conventional feature of prison dramas—in which such brutality is often inflicted upon the prisoners—so far as I know the scene in Jailhouse Rock has received scant critical commentary. The purpose of the scene is ambiguous. Why does the warden order a whipping as punishment rather than, say, solitary confinement? One might argue that the scene is “required,” as it were, because of the Hollywood production code: violent criminal behavior must be dealt with swiftly and without impunity. Impulsive, unable to control his inner rage, Elvis punches the prison guard (i.e., the Authority Figure), and so must be disciplined through violence himself. But of course the flogging isn’t merely or only disciplinary: he’s severely lacerated by the whip, as the facial reaction of his cellmate, Hunk Houghton (Mickey Shaughnessy), implies when he raises Elvis’s shirt in order to examine his back.

While watching Jailhouse Rock last night I realized I’d forgotten about the scene in which Elvis is flogged by order of the prison warden as a consequence of striking a guard following a food riot in the prison commissary. Presumably a conventional feature of prison dramas—in which such brutality is often inflicted upon the prisoners—so far as I know the scene in Jailhouse Rock has received scant critical commentary. The purpose of the scene is ambiguous. Why does the warden order a whipping as punishment rather than, say, solitary confinement? One might argue that the scene is “required,” as it were, because of the Hollywood production code: violent criminal behavior must be dealt with swiftly and without impunity. Impulsive, unable to control his inner rage, Elvis punches the prison guard (i.e., the Authority Figure), and so must be disciplined through violence himself. But of course the flogging isn’t merely or only disciplinary: he’s severely lacerated by the whip, as the facial reaction of his cellmate, Hunk Houghton (Mickey Shaughnessy), implies when he raises Elvis’s shirt in order to examine his back.

I was too young to see Jailhouse Rock in the movie theater when it was released in the fall of 1957. I do, however, vividly recall the first enactment of sadism I ever saw in the movie theater: the moment early on in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), when Lee Marvin (Liberty Valance, an outlaw) sadistically—like a man possessed—beats James Stewart (Ransom Stoddard, a lawyer) with his silver-handled whip. The crucial difference, of course, is that Liberty Valance is a sadistic villain, not a (presumably) benign prison warden as in Jailhouse Rock (the distinction being the legitimate vs. illegitimate uses of violence). Interestingly, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance was released almost precisely a year to the day after Marlon Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks (1961), which also featured a scene with a flogging, a scene in which Brando is lashed to a hitching post and viciously whipped by his old friend Dad Longworth (Karl Malden), who is now a Sheriff, that is, an official Authority Figure. Although One-Eyed Jacks was based on a novel by Charles Neider, its screenplay was co-written by Guy Trosper—who also wrote Jailhouse Rock.

In his definitive book on the subject, Acting in the Cinema (1988), James Naremore convincingly argues that it was Marlon Brando who brought to the cinema “a frighteningly eroticized quality to violence” (for example, in A Streetcar Named Desire), and it was Brando who in several films—On the Waterfront, One-Eyed Jacks, and The Chase—was “shown being horribly maimed or beaten by people who take pleasure in giving out punishment” (p. 230). Indeed, in both On the Waterfront and The Chase, Brando suffers especially vicious and prolonged beatings. But only in One-Eyed Jacks is he whipped, although the whip (the lash) figures prominently in the Brando film Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), in which it becomes a symbol of tyrannical authority. On the Waterfront, of course, precedes Jailhouse Rock, but in retrospect the importance of the scene in which Elvis is flogged while in the slammer cannot be underestimated: the presence of Elvis lends the whipping scene in Jailhouse Rock a degree of eroticized violence.

“Taste the whip” is a partial lyric in the Velvet Underground’s “Venus In Furs,” a demo for which (according to the box set Peel Slowly and See, a compilation of Lou Reed-era VU material) dates from July 1965—that is, after all of the aforementioned films save The Chase (filmed in 1965, but released in 1966). “Venus In Furs” later appeared on the first VU album, The Velvet Underground and Nico, released in March 1967, over a year before filming began on Donald Cammell and Nic Roeg’s Performance (filmed the late summer of 1968), which featured the brutal whipping of James Fox—a scene that was, incidentally, inspired by the scene of Dad Longworth’s whipping of Brando in One-Eyed Jacks.

I fully realize the obvious cinematic sources of inspiration (as opposed to the putative source, the more “respectable”—as in sophisticated—literary source, Sacher-Masoch’s nineteenth-century short novel Venus In Furs) for the Velvet Underground’s “Venus In Furs” likely were the silent 8mm and 16mm “stag” films models such as Bettie Page made in New York for exploitation filmmaker Irving Klaw in the 1950s rather than Brando movies, but the point cannot be overlooked. Klaw’s films, like the VU song, contain highly fetishized imagery of women clad in lingerie and stiletto heels enacting scenes of bondage, spanking, whipping, and domination—which is to say, the dark underbelly of modern urban life. But in terms of lyrical content, “Venus In Furs” is simply an aberrant reading of a pop song such as “Blue Velvet,” that is, a rock song with “adult” as opposed to “adolescent” content (R as opposed to G).

There are very few rock songs featuring the whip even though the whip has been associated with rock music since Jailhouse Rock in 1957. Most have followed the Velvet Underground’s lead—the whip as fetish object—as opposed to using the whip as a symbol of brutal authority (as in Neil Young’s “Southern Man”). Only those from the American South, such as The Allman Brothers Band (and Elvis), seem to understand that the whip cannot be extricated from the institution of slavery. And, of course, those from the so-called “Third World,” such as The Ethiopians.

10 Tracks Guaranteed To Whip It Up:

“Venus In Furs” – The Velvet Underground, The Velvet Underground and Nico (1967)

“Whipping Post” – The Allman Brothers Band, The Allman Brothers Band (1969)

“Southern Man” – Neil Young, After the Gold Rush (1970)

“When the Whip Comes Down” – The Rolling Stones, Some Girls (1978)

“Whip In My Valise” – Adam and the Ants, Dirk Wears White Sox (1979; 2004)

“Whip It” – Devo, Freedom of Choice (1980)

“Let It Whip” – Dazz Band, Keep It Live (1982)

“Love Whip” – The Reverend Horton Heat, Smoke ‘Em If You Got ‘Em (1991)

“The Whip” – The Ethiopians, Train to Skaville: Anthology 1966-1975 (2002)

“Wrong Side of the Whip” – Substitutes, The Exploding Plastic Inevitable (2005)

Friday, December 19, 2008

When The Whip Comes Down

Thursday, August 28, 2008

(Under) Cover

In the discourse about popular music, you’ll find that that the re-recorded version of a song previously recorded by an earlier artist is referred to as the “cover version” or, more often, “cover.” The implications of the word “cover” merit exploring. If you explore the issue in depth, then you’ll find that the word “cover” is a contranym or an antilogy—a word that is its own antonym (it is what it is not). A cover is an open response, a challenge made, to the received understanding of a previously existing musical text, but it also conceals (hides), and also protects (to ward off damage or injury). Hence the existence of the “cover version” invokes one of the many sets of oppositions animating popular music criticism, in particular the opposition between original and copy. What this means is that the original recording must be regarded as definitive (authentic), while any subsequent version must be considered a copy (a simulacrum, or a “fake”). But there are any number of other implications of the word “cover,” one of which means to efface or erase the original: to do a “cover version” is “cover up” (hide) a previous version. It has been argued that white rock musicians (e.g., Elvis Presley) covered (hid) “the blackness” of the songs they made famous to white listeners. A case in point would be Elvis’s cover of “Tutti Frutti,” made more palatable in his version to white listeners than Little Richard’s raunchier (first) version. Did Elvis’s version also efface the meaning of the song title in Italian, “all fruits,” one meaning of which is bisexuality? Is this what is meant by “cover,” as in hide, to obscure?

In the discourse about popular music, you’ll find that that the re-recorded version of a song previously recorded by an earlier artist is referred to as the “cover version” or, more often, “cover.” The implications of the word “cover” merit exploring. If you explore the issue in depth, then you’ll find that the word “cover” is a contranym or an antilogy—a word that is its own antonym (it is what it is not). A cover is an open response, a challenge made, to the received understanding of a previously existing musical text, but it also conceals (hides), and also protects (to ward off damage or injury). Hence the existence of the “cover version” invokes one of the many sets of oppositions animating popular music criticism, in particular the opposition between original and copy. What this means is that the original recording must be regarded as definitive (authentic), while any subsequent version must be considered a copy (a simulacrum, or a “fake”). But there are any number of other implications of the word “cover,” one of which means to efface or erase the original: to do a “cover version” is “cover up” (hide) a previous version. It has been argued that white rock musicians (e.g., Elvis Presley) covered (hid) “the blackness” of the songs they made famous to white listeners. A case in point would be Elvis’s cover of “Tutti Frutti,” made more palatable in his version to white listeners than Little Richard’s raunchier (first) version. Did Elvis’s version also efface the meaning of the song title in Italian, “all fruits,” one meaning of which is bisexuality? Is this what is meant by “cover,” as in hide, to obscure?

Viewed less pejoratively, that is, more benignly, the cover version is the re-interpretation of song previously recorded by another artist. But why is the “cover version” always singled-out or announced as a copy, that is, stigmatized as debased, as a duplicate? Why should anyone care? The paradox is, Americans generally have always privileged the re-interpretation, the re-invention, of an existing work. That is, since the Jazz Era, the improvisation—the artistic response—has been valued higher than the composer (the source of intentionality, the origin). Popular music privileges improvisation, while classical music privileges the composer. In other words, American popular music since the Jazz Era has valued idiom (style) over strict adherence to any pre-existing text.

The history of rock has numerous examples of the “cover” effacing the original (first) version. Where does one begin? Where does one stop?

Elvis Presley – That’s All Right (Mama)

The Beatles – Ain’t She Sweet

John Lennon – Stand By Me

Ringo Starr – You’re Sixteen

The Carpenters – Ticket to Ride

U2 – Helter Skelter

Jimi Hendrix – All Along the Watchtower

The Byrds – Mr. Tambourine Man

José Feliciano – Light My Fire

Van Morrison – It’s All in the Game

Shadows of Knight – Gloria

The Blues Brothers – Soul Man

Carl Carlton – Everlasting Love

Vanilla Fudge – You Keep Me Hangin’ On

Van Halen – You Really Got Me

Monday, August 11, 2008

Soulsville USA

A comment left by fred in connection with yesterday's Issac Hayes post reminded me that I neglected to provide a link to Memphis' great Stax Museum, "Soulsville USA." As I mentioned yesterday, Hayes got his start as a session musician at Stax back in the early 1960s. We visited Memphis three summers ago with the explicit purpose of visiting Graceland--a visit which we thoroughly enjoyed--but while we were installed at the Peabody Hotel there I also used the opportunity to visit a number of Memphis' historic sites, including the Stax Museum. Visiting the Stax Museum was not only a great educational experience, but a great thrill for me as well, as so many legendary musicians recorded at Stax's studios, among them Otis Redding, Booker T & the MGs, Isaac Hayes, and in a series of sessions in 1973, Elvis Presley. While the numbers of visitors who trek to Memphis every year in order to visit Graceland numbers in the millions, the Stax Museum is one of Memphis great treasures, and I urge anyone planning a visit to Memphis to schedule a visit there also.

A comment left by fred in connection with yesterday's Issac Hayes post reminded me that I neglected to provide a link to Memphis' great Stax Museum, "Soulsville USA." As I mentioned yesterday, Hayes got his start as a session musician at Stax back in the early 1960s. We visited Memphis three summers ago with the explicit purpose of visiting Graceland--a visit which we thoroughly enjoyed--but while we were installed at the Peabody Hotel there I also used the opportunity to visit a number of Memphis' historic sites, including the Stax Museum. Visiting the Stax Museum was not only a great educational experience, but a great thrill for me as well, as so many legendary musicians recorded at Stax's studios, among them Otis Redding, Booker T & the MGs, Isaac Hayes, and in a series of sessions in 1973, Elvis Presley. While the numbers of visitors who trek to Memphis every year in order to visit Graceland numbers in the millions, the Stax Museum is one of Memphis great treasures, and I urge anyone planning a visit to Memphis to schedule a visit there also.

Perhaps because of the Scientology connection, Isaac Hayes and Lisa Marie Presley were close friends; I was going to post a picture of the two together, but given everything surrounding Elvis's image is so heavily guarded and copyrighted, I have posted the following link instead. Hayes happened to pass away at the beginning of Elvis Week 2008, a celebration of Elvis and the culture from which he came. I strongly suspect that Elvis, were he alive, would give "Soulsville USA" a strong endorsement.

Saturday, July 5, 2008

"Dixie"

Having listened intently the past few days to the Band’s first album, Music From Big Pink (1968), today I found myself compelled to begin listening to the Band’s eponymous second album (released September 1969), the album that contains one of the Band’s most famous songs, The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down. A wonderfully dynamic, dramatic, and utterly compelling song, it was famously covered by Joan Baez, who had a hit single with the song about a year and a half after The Band's release. It was subsequently covered by Johnny Cash on his album John R. Cash (1975). In the context of the late 1960s and the Vietnam War, "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," while set during the days after the end of the bloody American Civil War, was generally interpreted as a song having an anti-war sentiment, while also invoking the Biblical parable of Cain and Abel. Presumably, the song was an attempt to identify and overcome the tensions of an American population divided in its support for the Vietnam War, to speak to both groups in a way that also acknowledged their mutual sense of patriotism.

Having listened intently the past few days to the Band’s first album, Music From Big Pink (1968), today I found myself compelled to begin listening to the Band’s eponymous second album (released September 1969), the album that contains one of the Band’s most famous songs, The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down. A wonderfully dynamic, dramatic, and utterly compelling song, it was famously covered by Joan Baez, who had a hit single with the song about a year and a half after The Band's release. It was subsequently covered by Johnny Cash on his album John R. Cash (1975). In the context of the late 1960s and the Vietnam War, "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," while set during the days after the end of the bloody American Civil War, was generally interpreted as a song having an anti-war sentiment, while also invoking the Biblical parable of Cain and Abel. Presumably, the song was an attempt to identify and overcome the tensions of an American population divided in its support for the Vietnam War, to speak to both groups in a way that also acknowledged their mutual sense of patriotism.

Like the Bible's Cain, the singer of "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," Virgil Caine (Cain?), is a farmer:

Virgil Caine [Cain?] is the name

And I served on the Danville train

'Til Stoneman’s cavalry came

And tore up the tracks again

In the winter of ‘65

We were hungry, just barely alive

By May the 10th Richmond had fell

It’s a time I remember oh so well

Chorus:

The night they drove Old Dixie down

And the bells were ringing

The night they drove Old Dixie down

And the people were singin’

They went Na, La, La, La, Na, Na . . .

Back with my wife in Tennessee

When one day she called to me

“Virgil quick come see—there goes Robert E. Lee”

Now I don’t mind choppin’ wood

And I don't care if the money’s no good

You take what you need

And you leave the rest

But they should never

Have taken the very best

[Chorus]

Like my father before me

I’m a workin’ man

Like my brother before me

Who took a rebel stand

He was just eighteen, proud and brave

But a Yankee laid him in his grave

I swear by the mud below my feet

You can't raise a [Cain?] Caine back up when he's in defeat

[Chorus]

The key poetic figure in the song is, of course, Dixie. There are few popular songs in American history more controversial than "Dixie," a song both adored and despised. Improbably, "Dixie" is a song that, prior to the Civil War, received ovations from both abolitionist Republicans and proslavery Democrats. After the Southern succession, it was adopted by the Confederacy as its national anthem. The song was played at Jefferson Davis's inauguration, but Abraham Lincoln so loved the song that he had it played at his second inauguration.

According to Michael Jarrett, "Dixie" was introduced on the Broadway stage on 4 April 1859 by Daniel Emmett, the founder of the first professional blackface minstrel troupe, and was an instant hit. But, as Jarrett observes,

...the popularity of "Dixie" resulted from the song's basic slipperiness. It seemed eager to serve all sorts of agendas and capable of insinuating itself into a variety of contexts. . . . "Dixie" is far more redolent of meaning than it is explicity meaningful. It functions as a poetic image. Generations of Americans, nostalgically drawn to the idyllic scene it calls them to conjure, have revered it. And generations, enraged and offended by the antebellum stereotypes it asks them to celebrate, have reviled it. (27)

Hence, the power of Dixie is in its multivalency: inherently ambiguous, it is a sentimental anthem associated with the American South, but also, consequently, a symbol of racism. But rather than be stymied by the figure's inherent cultural ambiguity, Mike Jarrett thinks we ought to listen to the song "anew." He writes:

How about straight, as a song of exile? Heard this way, it echoes psalms of captivity found in the Old Testament and anticipates the lamentations that abound in blues and, especially, reggae. Or how about ironically, as a signifying song? "Oh, I wish I was in the land of cotton. Yeah, like hell I do!" (28)

The slippery multivalency of "Dixie" allowed Mickey Newbury to incorporate the song into his well-known medley, "An American Trilogy," a song that, beginning in 1972, Elvis began performing during his live concerts. A portmanteau song celebrating the diversity of America, Newbury's "An American Trilogy" is composed of three songs: "Dixie" (South), "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" (North), and "All My Trials" (the individual citizen).

I raise these issues because today while listening to "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," I wondered why Elvis had never covered the song. Certainly he was capable of singing it. Certainly he was capable of singing it well. Did he reject it because he perceived it as a song of amelioration, a song about mending fences, and hence too much associated with the moderate Left (i.e., Joan Baez)? I turned to Elvis's rendition of "An American Trilogy," thinking that this song might well have been his "answer" song to the Band's earlier song. Having watched the Band's rendition of "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" as performed in The Last Waltz (1978; filmed late 1976,)--available on youtube.com--it struck me that there was a remarkable similarity between the orchestration and staging of The Last Waltz and the orchestration and staging of Elvis's Las Vegas shows, especially his arrangement of "An American Trilogy." In other words, the Band's performance of "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" in The Last Waltz was influenced by Elvis's earlier response to that very song, with his version of "An American Trilogy," also available on youtube.

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

The Pinch of Ridicule

In yesterday's blog, I said that nothing could appear a less promising topic than the movie career of Elvis Presley. Observing that movies in general have always been culturally ambiguous because they blur clear distinctions between art, commerce, and mass communication, I then immediately suggested that the films starring Elvis Presley are an exception to this culturally ambiguous status: they are not considered ambiguous at all, but rather as artless mass entertainment. In its most negative formulation, they are used as an example of Elvis’s tastelessness, made simply for crass commercial reasons: although nothing but tripe, they remain, nonetheless, quite profitable. What I didn't discuss yesterday are the reasons for this widespread cultural perception, and it's not clear to me that the reasons are due to the actual films themselves.

In yesterday's blog, I said that nothing could appear a less promising topic than the movie career of Elvis Presley. Observing that movies in general have always been culturally ambiguous because they blur clear distinctions between art, commerce, and mass communication, I then immediately suggested that the films starring Elvis Presley are an exception to this culturally ambiguous status: they are not considered ambiguous at all, but rather as artless mass entertainment. In its most negative formulation, they are used as an example of Elvis’s tastelessness, made simply for crass commercial reasons: although nothing but tripe, they remain, nonetheless, quite profitable. What I didn't discuss yesterday are the reasons for this widespread cultural perception, and it's not clear to me that the reasons are due to the actual films themselves.

The reasons for this perception are best explored in a remarkable essay written by a former teacher of mine, Linda Ray Pratt, titled "Elvis, or the Ironies of a Southern Identity," which can be found in Kevin Quain, Ed., The Elvis Reader (St. Martin's Press, 1992). In one of the best pieces ever written about Elvis, in the essay, writing as a Southerner herself, she discusses Elvis with the kind of understanding and empathy that those outside the culture often lack. I remember having brief conversations with her about Elvis--this back in the early 1980s, just a few years after his death, probably while she was thinking about the issues that ultimately emerged in this particular essay. She makes so many acute insights that it is impossible to list them all here, but here are a few insights that may help explain why Elvis's films are held in such widespread contempt, even by those who perhaps have never seen but one or two of them, and perhaps even by those who have never seen them at all--to see them would demonstrate a noticeable lapse in taste. Writing about Elvis in the context of Southern culture, she says:

C. Vann Woodward has said that the South's experience is atypical of the American experience, that where the rest of America has known innocence, success, affluence, and an abstract and disconnected sense of place, the South has know guilt, poverty, failure, and a concrete sense of roots and place.... These myths collide in Elvis. His American success story was always acted out within its Southern limitations. No matter how successful Elvis became in terms of fame and money, he remained fundamentally disreputable in the minds of many Americans. Elvis had rooms full of gold records earned by million-copy sales, but his best rock and roll records were not formally honored by the people who control, if not the public taste, the rewarding of public taste.... His movies made millions but could not be defended on artistic grounds. The New York Times view of his fans was "the men favoring leisure suits and sideburns, the women beehive hairdos, purple eyelids and tight stretch pants".... (96-97)

Observing that Elvis "remained an outsider in the American culture that adopted his music," she goes on to say:

Although he was the world's most popular entertainer, to like Elvis a lot was suspect, a lapse of taste.... The inability of Elvis to transcend his lack of reputability despite a history-making success story confirms the Southern sense that the world outside thinks Southerners are freaks, illiterates . . . sexual perverts, lynchers. I cannot call this sense a Southern "paranoia" because ten years outside the South has all too often confirmed the frequency with which non-Southerners express such views. Not even the presidency would free LBJ and Jimmy Carter from the ridicule.... And Elvis was truly different, in all those tacky Southern ways one is supposed to rise above with money and sophistication. (97)

Regarding the deification of the dead Elvis, she observes:

The apotheosis of Elvis demands . . . perfection because his death confirmed the tragic frailty, the violence, the intellectual poverty, the extravagance of emotion, the loneliness, the suffering, the sense of loss. Almost everything about his death, including the enterprising cousin who sold the casket pictures to National Enquirer, dismays, but nothing can detract from Elvis himself.... Greil Marcus wrote in his book Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock 'n' Roll Music that Elvis created a beautiful illusion, a fantasy that shut nothing out. The opposite was true. The fascination was the reality always showing through the illusion--the illusion of wealth and the psyche of poverty; the illusion of success and the pinch of ridicule; the illusion of invincibility and the tragedy of frailty; the illusion of complete control and the reality of inner chaos.... Elvis had all the freedom the world can offer and could escape nothing. (103)

Her final, acute insight is painfully true: by saying that Elvis could escape nothing, she means escape Southern mythology, both what he inherited as a Southerner by birth, and what someone from the South is perceived to be by non-Southerners (think: Deliverance). In a sense, his movie career failed because he was never allowed by the general culture to be a movie star. Even Jimmy Carter as president couldn't escape the stigma of being from the South: the mass media was brutal on him, his brother Billy, and even his daughter Amy. Although Dr. Pratt corrects an observation made by Greil Marcus in his essay "Elvis: Presliad," Marcus nonetheless cited portions of the above passage in his scathing review of Albert Goldman's biography Elvis (1981), a biography I've cited on a few occasions. Her essay helps immensely to explain why so many were offended by Goldman's biography of Elvis: his (perhaps unconscious) contempt for the South and for Elvis's Southern identity taints almost every page.

But rather than fixate on the mote in our neighbor's eye, perhaps we ought to examine the sources and motivations for our own perceptions, in this case why Elvis's films are widely considered jokes, even by those who may have never seen them, or seen very few. To extrapolate a bit on Linda Ray Pratt's essay, we might say that those perceptions may largely be determined by factors that have nothing to do with the films themselves.

Tuesday, June 24, 2008

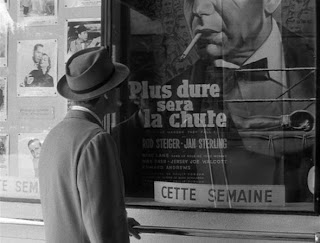

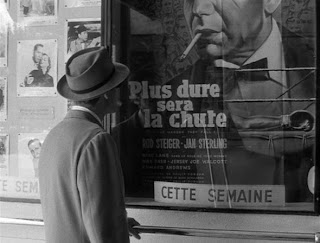

The Harder They Fall

Movies are so familiar to us that they are widely considered nothing more than “entertainment.” Naïvely, we assume that movies are easier to understand than literature--literature being regarded as "serious," and therefore "art." The fact is, movies are entertaining . . . and they are also complex. As a result, they are culturally ambiguous, because they blur simplistic distinctions between art, entertainment, and mass communication.

Movies are so familiar to us that they are widely considered nothing more than “entertainment.” Naïvely, we assume that movies are easier to understand than literature--literature being regarded as "serious," and therefore "art." The fact is, movies are entertaining . . . and they are also complex. As a result, they are culturally ambiguous, because they blur simplistic distinctions between art, entertainment, and mass communication.

Strangely, though, movies starring Elvis Presley are the exception to this culturally ambiguous status of the movies: they are not considered ambiguous at all, but rather as artless, and therefore mass (as in “mind-numbing”) entertainment. In its most negative formulation, they are used as an example of Elvis’s (or the Colonel’s) tastelessness, made because of his (or the Colonel’s) desire for the “fast buck.” Because they are considered tasteless, they are, therefore, as a consequence, benign, an exception to much of the writing about Hollywood that focuses on Hollywood’s (bad) influence on American life and values. Elvis's films are nostalgic, innocuous (formulaic), and therefore harmless (non-controversial).

As a topic, therefore, nothing could appear less promising than the movie career of Elvis Presley. But, as Robert Ray writes, the

situation probably has less to do with Elvis’s own contributions to his movies that with the films themselves, most of them specious, formulaic representations of what the pre-rock generation of producers, writers, and directors who made them thought was “youth culture.” (“The Riddle of Elvis-the-Actor,” p. 102)

Of course, the general criticism of Elvis’s movies is largely directed at the films he made in the 1960s, after his stint in the U. S. Army: G.I. Blues (1960) through A Change of Habit (1969). So, for the sake of convenience, let’s consider the four films Elvis made in the 1950s: Love Me Tender (1956), Loving You (1957), Jailhouse Rock (1957), and King Creole (1958). The year 1956, of course, marks the year Elvis emerged as a powerful cultural force—in America and elsewhere (think of John Lennon’s remark, “Before Elvis there was nothing”).

Jean-Luc Godard’s one explicit film about the influence of American culture on the rest of world is Masculine-Feminine (1966), the famous film exploring the lives of "the children of Marx and Coca-Cola." But long before Masculine-Feminine, there was, of course, Breathless (1960). Regarding Breathless, I’ve always wondered why, given Michel Poiccard’s (Jean-Paul Belmondo’s) apparent age (Belmondo was 26 at the time the film was made, although he looks younger), he idolized Bogart, when the more obvious figure, it seems to me, should have been Elvis. (Belmondo was born in 1933, Elvis in 1935.)

For many critics, the key scene in Breathless that is structured to reveal how Michel Poiccard imitates the character (“image”) of Humphrey Bogart is the moment when he encounters Bogart’s face on a movie poster. Here, Poiccard approaches the large poster: The poster in which Bogart’s image appears is the French poster of The Harder They Fall (1956), Bogey’s last film (he was to die in January 1957), set in the boxing world. After studying the poster, Poiccard moves to his left, to study a display of 8x10 movie stills:

The poster in which Bogart’s image appears is the French poster of The Harder They Fall (1956), Bogey’s last film (he was to die in January 1957), set in the boxing world. After studying the poster, Poiccard moves to his left, to study a display of 8x10 movie stills: In particular, he studies an image of Bogart . . .

In particular, he studies an image of Bogart . . .

. . . captivated by it, the cigarette hanging from his lips just as the cigarette does from Bogey's in the large movie poster. Meanwhile, he continues to study Bogey's image: . . . as Bogey returns his gaze . . .

. . . as Bogey returns his gaze . . . The cigarette, of course, is a signifier closely associated with American culture, particularly the American G.I. during WWII (and Bogey in Casablanca). The scene concludes with Poiccard's imitation of Bogey's characteristic gesture, the thumb raking across the upper lip, indicating contemplation, and, occasionally, indecisiveness:

The cigarette, of course, is a signifier closely associated with American culture, particularly the American G.I. during WWII (and Bogey in Casablanca). The scene concludes with Poiccard's imitation of Bogey's characteristic gesture, the thumb raking across the upper lip, indicating contemplation, and, occasionally, indecisiveness: The standard interpretation of this scene is that we are to understand Michel Poiccard consciously models his life on the figure of movie star Humphrey Bogart—he wishes to live a life like his (or at least, his life in American films noir). For some critics, Michel Poiccard’s criminal behavior serves as a sort of Godardian self-inscription, given that Godard, apparently, was a delinquent as a youth. But what happens to this sequence if we substitute the more obvious (at the time) figure of American cultural influence, movie star Elvis Presley in this sequence? Poiccard approaches the marquee . . .

The standard interpretation of this scene is that we are to understand Michel Poiccard consciously models his life on the figure of movie star Humphrey Bogart—he wishes to live a life like his (or at least, his life in American films noir). For some critics, Michel Poiccard’s criminal behavior serves as a sort of Godardian self-inscription, given that Godard, apparently, was a delinquent as a youth. But what happens to this sequence if we substitute the more obvious (at the time) figure of American cultural influence, movie star Elvis Presley in this sequence? Poiccard approaches the marquee . . .

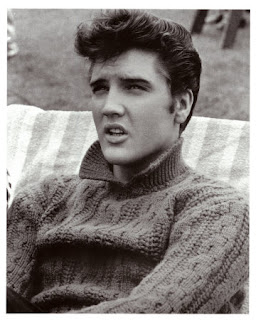

. . . but instead of the poster of The Harder They Fall, it's the poster of Jailhouse Rock: There's no cigarette of course, and there isn't the large image of Bogart's older, chiseled face, but there is the image of Elvis as both jailbird and as seductive sex symbol. In this revised sequence, Poiccard moves to his left, just as in the original . . .

There's no cigarette of course, and there isn't the large image of Bogart's older, chiseled face, but there is the image of Elvis as both jailbird and as seductive sex symbol. In this revised sequence, Poiccard moves to his left, just as in the original . . . . . . but instead of Bogey's image, it is Elvis's image from Jailhouse Rock:

. . . but instead of Bogey's image, it is Elvis's image from Jailhouse Rock: He studies the image as before . . .

He studies the image as before . . . . . . while Elvis returns his gaze . . .

. . . while Elvis returns his gaze . . . Without the cigarette, Poiccard's (Belmondo's) facial expression seems remarkably closer to Elvis's than it does Bogart's:

Without the cigarette, Poiccard's (Belmondo's) facial expression seems remarkably closer to Elvis's than it does Bogart's: Of course, this imaginary sequence would conclude without the expressive gesture of the thumb across the lip to suggest the implicit identification Poiccard has with Bogey, and hence the loss of all the meanings compressed into the image of Bogart.The question is how and in what way the sequence is altered by the substitution of one American icon with another.

Of course, this imaginary sequence would conclude without the expressive gesture of the thumb across the lip to suggest the implicit identification Poiccard has with Bogey, and hence the loss of all the meanings compressed into the image of Bogart.The question is how and in what way the sequence is altered by the substitution of one American icon with another.

The gesture of the thumb across the lip recurs at different times in Breathless, but what if, instead of the lip gesture, Poiccard/Belmondo imitates, say, Elvis's gesture (sans hat) of flipping the head backwards to clear the hair from his eyes? He can't, because Poiccard is an anti-hero inspired by the characters of an older Hollywood than the Hollywood in which Elvis arrived for his first film in 1956. The fact is, Michel Poiccard is a doomed Hollywood anti-hero, but a charmingly nostalgic one. Elvis wasn't appropriate for Breathless because, ironically, he was too contemporary (a fear realized by the ambiguous figure of Patricia Franchini/Jean Seberg, the hip, promiscuous American girl who is also the film's femme fatale). The charm of Michel Poiccard is that he remains a comfortably familiar figure, even for French audiences. The irony is that in 1959, when Breathless was being made, Elvis, on leave from the U. S. Army, visited Paris. I like to imagine that in those cinéma-vérité scenes shot on the Champs-Élysées, Elvis was one of those figures standing in the background. Robert Ray argues that Elvis's style of acting would have been appropriate for Godardian cinema, imagining him, for instance, in a sequel to Masculine-Feminine. The idea is not as silly as it sounds: imagine the possibilities of Elvis starring in a Godard film. It would have been something to see.

Saturday, June 21, 2008

Elvis & His Guru

Improbably, this morning’s Los Angeles Times contained an article on the resurgence of interest in spiritualist Manley Palmer Hall (1901-1990), mentioning that a clip from the one film in which Hall made an appearance--the astrological murder mystery When Were You Born? (1938)--was shown as part of an “Occult L.A.” film program curated by Erik Davis. “Occult L.A.” was a program devoted to exploring what is, apparently, an ongoing fascination with the occult that has a long history in, and around, Los Angeles. Although skeptical at first, I decided there may be some merit to the idea that Los Angeles is peculiar in its obsession with the occult, if for no other reason than the way these occult ideas were transmitted by means of Larry Geller (pictured above, with Elvis), whom Elvis met in Los Angeles in 1964 when Geller became his hairdresser. Regarding the so-called “high priest” of the occult Manley Palmer Hall—subject to a newly published biography by L. A. Times staff writer Louis Sahagun—the article avers that “even Elvis was a fan, sending Priscilla Presley to one of the world renowned orator’s lectures because he was afraid of getting mobbed himself.”

Improbably, this morning’s Los Angeles Times contained an article on the resurgence of interest in spiritualist Manley Palmer Hall (1901-1990), mentioning that a clip from the one film in which Hall made an appearance--the astrological murder mystery When Were You Born? (1938)--was shown as part of an “Occult L.A.” film program curated by Erik Davis. “Occult L.A.” was a program devoted to exploring what is, apparently, an ongoing fascination with the occult that has a long history in, and around, Los Angeles. Although skeptical at first, I decided there may be some merit to the idea that Los Angeles is peculiar in its obsession with the occult, if for no other reason than the way these occult ideas were transmitted by means of Larry Geller (pictured above, with Elvis), whom Elvis met in Los Angeles in 1964 when Geller became his hairdresser. Regarding the so-called “high priest” of the occult Manley Palmer Hall—subject to a newly published biography by L. A. Times staff writer Louis Sahagun—the article avers that “even Elvis was a fan, sending Priscilla Presley to one of the world renowned orator’s lectures because he was afraid of getting mobbed himself.”

There may be some truth to this anecdote. Elvis’ interest in Manley Palmer Hall’s writings dates from 1964 or after, when he fell under the influence of Larry Geller, who introduced Elvis to any number of occult writings over the next few years. According to Albert Goldman, in his controversial biography Elvis (1981), Larry Geller introduced Elvis to the following books, among others:

Vera Stanley Adler, The Initiation of the World

David Anrias, Through the Eyes of the Masters

Alice A. Bailey, Esoteric Healing

McDonald McBain, Beyond the Himalayas

Anne Besant, The Masters

H. P. Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine; The Voice of Silence

Paul Brunton, The Wisdom of the Overself

Richard Maurice Bucke, Cosmic Consciousness

Joel Goldsmith, The Infinite Way

Manley Palmer Hall, The Mystical Christ; The Secret Teachings of All Ages

Max Heindel, The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception

C. W. Leadbetter, The Inner Life

The Leaves of Morya's Garden

Nicholas Roerich, Flame in Chalice

Dane Rudhyar, The Life and Teachings of the Masters of the Far East

Tibetan Book of the Dead

The Urantia Book

As Goldman points out, most of these books pre-date Elvis's birth by many years, many of them dating back to the days before and after World War I, when books on spiritualism were tremendously popular. Indeed, Manley Palmer Hall arrived in Los Angeles in 1919, the year after the first World War ended, and soon his career as a student of esoteric and occult religions began. In fact, books on spiritualism were received so enthusiastically around this time period that T. S. Eliot used it in The Wasteland (1922) as a symbol of degradation of myth and ritual in the modern world.

Elvis read these books with great care, writes Goldman, as was evident

from the appearance of his copies, dog-eared, travel-stained, heavily underscored on almost every page. Elvis committed many of the key passages to memory and would recite them aloud while Larry Geller held the book like a stage prompter.... The particular tradition of spiritualism from which stem most of the writings to which Elvis Presley devoted himself for the balance of his life was established in the 1870s in New York City by the notorious and fascinating Madame Blavatsky.... one little volume puporting to be translations by Blavatsky of the most ancient runes of Tibet, The Voice of Silence, was such a favorite of Elvis's that he sometimes read from it onstage and was inspired by it to name his own gospel group, Voice. (Avon paperback edition, 1982, p. 436)

An autodidact, Elvis became especially fascinated by a book titled The Impersonal Life (1917) which carries the name Joseph Benner as its author, although the author purports merely to be the amanuensis of the Divine Being--in other words, the vehicle through which God speaks. According to Goldman, Elvis gave away "hundreds of copies of this book, like an eager evangelist distributing a favorite tract" (p. 439).

Note that the word "spiritualism" as I'm using it does not mean formal religion (orthodoxy). To be "spiritual" does not mean "religious" in the orthodox sense. If you have the occasion to listen to some of Elvis' later live recordings, pay attention for his references to the ideas in these old and sundry books.

Incidentally, Erik Davis' "Occult L.A." program apparently screened an extremely rare film by Curtis Harrington that I'd never heard of, titled Wormwood Star (1956), an early short by Harrington featuring the poetry and painting of occultist Marjorie Cameron, who appeared in Kenneth Anger's Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954) and, later, in Harrington's fine film Night Tide (1961), featuring Dennis Hopper.

Thursday, June 12, 2008

The Trip

In my last blog entry I noted the fact that 1966 saw four LPs released bearing the word "psychedelic": Timothy Leary et al.'s LP recording The Psychedelic Experience (a spoken-word condensation of passages from his co-authored 1964 book of the same title), the Deep's Psychedelic Moods (perhaps the first rock album released with the word "psychedelic" in the title), The Blues Magoos' Psychedelic Lollipop, and the 13th Floor Elevators' The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators. Serendipitously, later that day, after posting my blog on the subject, I took a little time to watch Warner's latest DVD issue of Elvis Presley's 22nd film, Spinout (MGM, 1966; 92m 43s), the soundtrack to which I realized was released in October of that year, that is, about the same time as the aforementioned "psychedelic" rock albums. I was struck by the odd juxtaposition it might have made, the soundtrack to Spinout sitting side-by-side in the record bins with albums bearing titles such as Psychedelic Lollipop and Psychedelic Moods. And yet, the more I've thought about it, the less odd it has become. I've concluded that the juxtaposition is not so much odd or strange as it is an illustration of one of those proverbial moments in history when one world was not yet dead and the other not yet born.

In my last blog entry I noted the fact that 1966 saw four LPs released bearing the word "psychedelic": Timothy Leary et al.'s LP recording The Psychedelic Experience (a spoken-word condensation of passages from his co-authored 1964 book of the same title), the Deep's Psychedelic Moods (perhaps the first rock album released with the word "psychedelic" in the title), The Blues Magoos' Psychedelic Lollipop, and the 13th Floor Elevators' The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators. Serendipitously, later that day, after posting my blog on the subject, I took a little time to watch Warner's latest DVD issue of Elvis Presley's 22nd film, Spinout (MGM, 1966; 92m 43s), the soundtrack to which I realized was released in October of that year, that is, about the same time as the aforementioned "psychedelic" rock albums. I was struck by the odd juxtaposition it might have made, the soundtrack to Spinout sitting side-by-side in the record bins with albums bearing titles such as Psychedelic Lollipop and Psychedelic Moods. And yet, the more I've thought about it, the less odd it has become. I've concluded that the juxtaposition is not so much odd or strange as it is an illustration of one of those proverbial moments in history when one world was not yet dead and the other not yet born.

I happen to be reading Thomas Hine's very interesting book Populuxe (Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), a study of the unprecedented decade of mass consumption in America--for mass-produced houses, furniture, and machines--that occurred during the decade 1954-1964. Elvis, of course, first recorded for Sun Records in 1954, and 1964 was the year the Beatles "invaded" America, Elvis and the Beatles serving as bookends for that watershed decade. For Thomas Hine, one of the key moments that defined the end of the Populuxe era was the assassination of President Kennedy on 22 November 1963; the Beatles arrived in New York on 7 February 1964, seventy-seven days later--the one event signaled the end of American optimism, the other the end of American cultural dominance in the world. By the time the New York World's Fair opened in April 1964--which "should have been a Populuxe extravaganza" according to Hine--"the feeling of bland self-satisfaction with material comfort that had been so characteristic of the Populuxe era was gone" (167). He writes:

In 1959 Nixon could use a washing machine to symbolize America and it was a masterstroke, but in 1964 it would have been ridiculous.... In its story on the opening of the 1964 World's Fair, Life, that perennial cheerleader for the future and celebrator of the promise of America, called the fair "all candy-bright and gay in a world that is in fact harsh." This was a drastic piece of revisionism, asserted with such casualness that whole hierarchies of editors must have assumed its truth. Although the World's Fair planners could never have anticipated it, the fair came during a period of national atonement. (169)

Elvis can be considered the supreme symbol of America's Populuxe era, moribund by 1966. A highly visible public figure, Elvis in some sense was the very epitome of the American consumer of that era, avidly accumulating material things, including those two things so essential to American life, cars and homes. A movie such as Spinout, so obsessed as it is with the symbol of the fast car, money, and the trappings of privilege, seems more ideally suited to the Populuxe era, not the mid-60s era characterized by foreign "invasions," represented (for instance) by the Beatles and the Volkswagen. Elvis was sexually provocative, erotic, vigorous and energetic, but most importantly, American. In contrast, the Beatles were cute, nice (but not serious), ironic--and foreign. I tend to agree with Hine that 1964 marks the end of one era and the beginning of another; I wouldn't necessarily call the post-Populuxe era the psychedelic era, although it is a remarkable historical coincidence that on 14 June 1964, Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters--among them Timothy Leary and Beat figure Neal Cassady--embarked in the bus named "Furthur" (a portmanteau containing the words "further" and "future") on a cross-country journey headed for the New York World's Fair.

As the supreme symbol of the Populuxe era, it is therefore perhaps not coincidental that Elvis starred in It Happened at the World's Fair (released in April 1963, near the end of that era), that used as a setting the Seattle World’s Fair, otherwise known as the Seattle Century 21 Exposition, held 21 April-21 October 1962, the unofficial symbol of which became the Space Needle. Nor is it entirely coincidental that the Merry Pranksters, in the early days of the psychedelic era, took off on a trip in June 1964 in a bus painted in Day-Glo colors headed toward the New York World's Fair, an event that, while not a total bust, did not have "the kind of overwhelming enthusiasm for such a grand excursion into the future that might have been found only a few years before" (Hine, 168). Writes Hine: "Americans seemed to be getting a bit jaded about the future; it had been around for too long a time" (168). Hence it is a mistake to see a film such as Spinout as a sort of quaint, "innocent" museum piece from the 1960s: it was an anachronism even when it was made.

As for the film that Ken Kesey started making at the time (that remains unfinished), to have been titled The Merry Pranksters Search for the Kool Place, Katie Mills thinks it quite possibly influenced the Beatles' Magical Mystery Tour in 1967 and perhaps even, later, Easy Rider (1969). I'll explore that in a future blog.

Monday, April 28, 2008

The Reassurance of Fratricide

The title of my entry is taken from Benedict Anderson’s book, Imagined Communities (Revised Edition, Verso, 1991), and his discussion of memory and forgetting, that is, the way the writing of history constitutes an act that consists both of remembering (anamnesis) and its opposite, amnesia. Since history is written by the victors, the Civil War, for example, is consequently the enactment of the hostility of “brother against brother,” that is, the story of Cain and Abel (hence the inspiration for his homiletic parody, "the reassurance of patricide"). Had the Confederacy won, however, it might well have been about something, speculates Anderson, "quite unbrotherly" (201).

The title of my entry is taken from Benedict Anderson’s book, Imagined Communities (Revised Edition, Verso, 1991), and his discussion of memory and forgetting, that is, the way the writing of history constitutes an act that consists both of remembering (anamnesis) and its opposite, amnesia. Since history is written by the victors, the Civil War, for example, is consequently the enactment of the hostility of “brother against brother,” that is, the story of Cain and Abel (hence the inspiration for his homiletic parody, "the reassurance of patricide"). Had the Confederacy won, however, it might well have been about something, speculates Anderson, "quite unbrotherly" (201).

Fratricide: the story of brother against brother, the mythic archetype of Cain and Abel. Elvis Costello wrote “Blame it on Cain,” but I choose to blame it on Elvis, primarily for the act of fratricide that drives the plot of his first movie, Love Me Tender (1956). In his first film role, Elvis played Clint Reno, who during the Civil War remained home while his older brother, Vance (Richard Egan), fought on the side of the Confederacy. At war’s end, Vance returns home to discover that during his absence his former beloved, Cathy (Debra Paget), has married his brother Clint. But...there is an alibi, or excuse, for this state of affairs, because Clint and Cathy had been told that Vance had been killed in battle. Predictably, as one might expect, the story moves inexorably toward its tragic conclusion, foregrounded as it is by brotherly strife.

Since Elvis, or perhaps because of Elvis, there have been many songs reenacting, in various guises, the story of Cain and Abel. Here are a few representative recordings:

The Boomtown Rats, "I Don't Like Mondays"

The Buggles, “Video Killed the Radio Star”

Johnny Cash, “Frankie and Johnny” & “Folsom Prison Blues”

The Doors, “The End” (parricide) & “Riders on the Storm”

The Eagles, “Doolin-Dalton”

Lefty Frizzell, “Long Black Veil”

Lorne Greene, "Ringo"

Jimi Hendrix, “Hey Joe”

Robert Johnson, "32-20 Blues"

The Kingston Trio, “Tom Dooley”

Vicki Lawrence, “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia”

The Louvin Brothers, “Knoxville Girl”

Bob Marley, “I Shot the Sheriff”

Crispian St. Peters, “The Pied Piper”

Pink Floyd, "Careful With That Axe, Eugene"

Gene Pitney, "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance"

Stan Ridgway, “Peg and Pete and Me” & "Down the Coast Highway"

Marty Robbins, “El Paso" & "Big Iron"

Jimmy Lee Robinson, “I Shot a Man”

Kenny Rogers and the First Edition, “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town”

The Rolling Stones, “Midnight Rambler”

Bruce Springsteen, “Nebraska”

Hank Snow, “Miller’s Cave”

Suicidal Tendencies, “I Shot the Devil”

Talking Heads, “Psycho Killer”

Hank Williams, Jr., “I’ve Got Rights”

Neil Young, “Down by the River” & “Southern Man”

Monday, March 31, 2008

Critical Overcomprehension

In his witty and insightful book, Adventures in the Screen Trade (1983) William Goldman, a highly successful screenwriter (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) but also a wry critic of Hollywood, observes that a Hollywood studio head is very much like the manager of a baseball team: each and every day he wakes up knowing that sooner or later he is going to be fired.

In his witty and insightful book, Adventures in the Screen Trade (1983) William Goldman, a highly successful screenwriter (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) but also a wry critic of Hollywood, observes that a Hollywood studio head is very much like the manager of a baseball team: each and every day he wakes up knowing that sooner or later he is going to be fired.

No doubt the vast majority of today’s critics--of the theater, movies, music, contemporary fine arts--wake up each morning in a similarly precarious position, not necessarily thinking they will be fired from their privileged critical occupation, but that most certainly and with a creeping, unavoidable inevitability--like the day of their death--they will be wrong. What is a critic’s deepest fear? To have erred in judgment, to have made the wrong call, in short, to have missed the boat.

No music critic wants to miss the boat--to have critically underestimated, or what’s worse, to have dismissed the next Velvet Underground, for instance--so in order to avoid making such an unwitting mistake, the critic engages in what Robert Ray, employing a term coined by Max Ernst, calls overcomprehension (How a Film Theory Got Lost, Indiana University Press, 2001, p. 82). Ray writes:

Aware of previous mistakes, reviewers become increasingly afraid to condemn anything....Hence ... [one] ... of modern criticism’s ... great dangers, what Max Ernst called “overcomprehension” or “the waning of indignation”.... (82)

No critic, of course, can see beyond the curtain of time. Time is the ultimate critic, and the critic’s limited perspective doesn’t allow him to see beyond his own pitifully narrow moment in history. Critical overcomprehension--the act of giving every new record an equally glowing reception--is a result of the critic’s deep fear of being judged by history as wrong. No one wants to be, for instance, television critic Jack Gould, who reviewed the Milton Berle Show appearance of Elvis Presley for the New York Times in 1956:

Mr. Presley has no discernible singing ability. His specialty is rhythm songs which he renders in an undistinguished whine; his phrasing, if it can be called that, consists of the stereotyped variations that go with a beginner's aria in a bathtub. For the ear, he is an unutterable bore, not nearly so talented as Frank Sinatra back in the latter's rather hysterical days at the Paramount Theater. (qtd. in Robert Ray, 80)

Of course, as Ray points out, Gould’s kind of critical error had its own unintended consequences: such gross critical mistakes, Ray argues, led to “rejection and incomprehensibility as promises of ultimate value” (82). In other words, if an album sold poorly, or the artist who recorded it was given scant attention--or worse, completely neglected in his time, the record must therefore be great, perhaps even a masterpiece.

I suppose we all have adopted our favorite neglected artist, the artist whose critical neglect or, if you will, martyrdom, ironically, is the sign of greatness, of ultimate value. In my own music collection, this sort of artist is represented by, among others, Tim Buckley and Phil Ochs.

But I’m wondering, what do we do with the opposite case, the artist who is the critical establishment’s darling and whose records we therefore own, but never play? (Perhaps I'm a heretic, but I find myself playing only certain selections of Trout Mask Replica, not the entire disc.) The presence of both sorts of records, side by side in our music collections, reveals the persistent problem of what Robert Ray calls the Gap, the problem of assimilation, the failure of a new or unusual artistic style to be made intelligible to the public. Although rock 'n' roll is now over fifty years old, we still find ourselves struggling to fully comprehend its challenges and complexities, rather like a person who has difficulty reading or understanding the lines indicating contours and elevations on a topographic map.

Monday, March 24, 2008

Thursday, January 28, 1960: Why Are There Lyrics, Anyway?

Four years earlier than the above date, in his first national television appearance on the Dorsey Brothers’ Stage Show, broadcast January 28 1956, Elvis Presley chose to open with “Shake, Rattle, and Roll,” a song that Frank Sinatra, for one, would never have condescended to perform. Sinatra probably snorted in derision at Elvis’s second song that evening, too: “Flip, Flop & Fly.” Three months later, when Elvis again appeared on the Stage Show, he sang “Tutti Frutti.” Forget what young females thought about Elvis’s bad boy sneer, his gyrating hips, his wiggling and shimmying, his clamorous shouts and erotic moans—that’s legendary. The more important question is, why did Elvis choose to perform, on a national stage, such “nonsensical” songs?

Four years earlier than the above date, in his first national television appearance on the Dorsey Brothers’ Stage Show, broadcast January 28 1956, Elvis Presley chose to open with “Shake, Rattle, and Roll,” a song that Frank Sinatra, for one, would never have condescended to perform. Sinatra probably snorted in derision at Elvis’s second song that evening, too: “Flip, Flop & Fly.” Three months later, when Elvis again appeared on the Stage Show, he sang “Tutti Frutti.” Forget what young females thought about Elvis’s bad boy sneer, his gyrating hips, his wiggling and shimmying, his clamorous shouts and erotic moans—that’s legendary. The more important question is, why did Elvis choose to perform, on a national stage, such “nonsensical” songs?

One of the reasons Elvis was derided early on was that his choice of material seemed so ludicrous: “Flip Flop & Fly”? “Tutti Frutti”? Why not the deep yearning of classic ballads such as “In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning” or “When Your Lover Has Gone”? Why choose songs that are so devoid of substance—so apparently trivial? Why not perform the old standards instead? Frank Sinatra was so incensed by Elvis’s music that he wrote a magazine article condemning rock as “the most brutal, ugly, degenerate, vicious form of expression it has been my displeasure to hear.” He averred that rock ‘n’ roll is “sung, played, and written for the most part by cretinous goons and by means of its almost imbecilic reiterations and sly, lewd—in plain fact—dirty lyrics, it manages to be the martial music of every sideburned delinquent on the face of the earth.” (qtd. from Kitty Kelley, His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra, Bantam Books, p. 277).

However, according to Donald Clarke, by the time Elvis appeared on the historical scene, the music business wasn’t the same as it had been when Sinatra began his career slightly over a decade earlier. By the early 1950s, “good white songs were becoming scarce. The Berlins, Gershwins and the rest had died or retired, and the classic songs they had written could not be imitated.” Hence, Elvis never had access to the sort of material to which Sinatra had access (“standards”), and perhaps that made all the difference. (As a corollary, Elvis was never offered the sort of strong dramatic roles in movies that Sinatra was offered, either.) The composers of many of Elvis’s early songs were black, who were writing for the black music market, and who had a different sensibility than the Berlins and Gershwins. So, in answer to the question as to why Elvis chose to perform songs such as “Flip Flop & Fly” and “Tutti Frutti,” the reason is because Elvis chose songs that didn’t sound like anything else. But to Frank Sinatra, if songs weren’t standards, they were aberrations.

Simon Frith offers a way of understanding the difference between Sinatra and Elvis by referring to Dave Laing’s book, Buddy Holly (1972). Laing says that those interested in understanding rock music need to have the musical equivalent of film studies’ distinction between the auteur and the metteur en scene. According to Laing:

The musical equivalent of the metteur en scene is the performer who regards a song as an actor does his part—as something to be expressed, something to get across . . . . The vocal style of the singer is determined almost entirely by the emotional connotations of the words.

Frank Sinatra, then, was the musical equivalent of the metteur en scene. In contrast, says Laing, the rock auteur

is determined not by the unique features of the song but by his personal style, the ensemble of vocal effects that characterize the whole body his work.

Elvis, then, was the equivalent of an auteur: the meaning of the song is not simply organized around the words, but rather in the exceptional nature of his singing style. Sinatra condemned Elvis because he didn’t understand his music, nor could he, at the time, quite grasp the historic rupture in American popular music that Elvis represented. In film historical terms, Sinatra was the old, “classical” Hollywood, while Elvis anticipated the age—our age—of the independent film, the age of the auteur.

Saturday, March 22, 2008

Tuesday, January 26, 1960: Alien Sex

One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh...

One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh...

Having turned 25 years old in January, 1960, Elvis would have turned 73 years old in January of this year. Sharing the same birthday as Elvis, January 8, David Bowie turned 61 a couple of months ago (having turned 13 years old in January, 1960). In a few more months, Mick Jagger will be 65. (Astonishingly, Bill Wyman of the Stones already celebrated his 71st birthday.) In the history of rock ‘n’ roll, eventually it may come to pass that British artists such as Jagger and Bowie will be perceived as more provocative rock stars than Elvis Presley, although Elvis in a very real sense created them, that is, made them both possible, enabling their later elaborations on the image of the (white) rock star he pioneered.

One reason for this eventuality may be that both Bowie and Jagger were willing to experiment with their masculine image much more than Elvis. Although extraordinarily erotic to a generation of young women, Elvis never tried any such experimentation--it probably never occurred to him. What this difference suggests, among other things, is that Bowie’s and Jagger’s particular allure is not Elvis’s—and never was. Critic Greil Marcus has argued that what Elvis did was to purge the Sunday morning sobriety from folk and country music and expunge the dread from the blues. In doing so, he transformed a regional music into a national music, and in doing so invented party music. Elvis popularized an amalgam of musical forms and styles into “rock ‘n’ roll,” a black American euphemism for sexual intercourse. What the Rolling Stones did to rock music (and Bowie after them) some years after Elvis made sex an integral part of rock music’s appeal, was to infuse rock with a bohemian theatricality, at first through the key figure of Brian Jones, who was the first British pop star to cultivate actively a flamboyant, androgynous image. For a time, Jones even found his female double in Anita Pallenberg. Brian Jones and the Stones thus re-introduced into rock music its erotic allure, and hence made it threatening (again).

History will recognize that the cultivated androgyny and transvestitism of 1960s rock stars such as Jagger and Bowie destabilized and subverted stable categories of the self and sexual identity, which is why as cultural practices they were perceived by some as so threatening and so subversive to genteel, bourgeois culture. (Indeed, Brian Jones seems to have had deep disdain for middle-class puritanism and sexuality morality.) By the late 1960s and early 1970s, roughly four decades ago, rock music had become synonymous with decadence. The connection was cemented when Mick Jagger appeared in Donald Cammell and Nic Roeg’s Performance (1970) as a bohemian rock star living in a ménage à trois with two women--one of whom was Anita Pallenberg. A few years later, in 1976, David Bowie appeared as a sexually ambiguous alien, Thomas Jerome Newton, in The Man Who Fell to Earth (although, as David Cammell recently told me, Peter O'Toole was first considered for the part of Newton.) The Bowie character was similar to the Michael Rennie character (Klaatu, aka “Mr. Carpenter”) in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) by virtue of his possessing advanced technology. But he was utterly unlike the Rennie character in that his alien sexuality was foregrounded; it was essential to defining his difference. (Michael Rennie is to The Day the Earth Stood Still what Elvis Presley is, now, to rock culture—a benign, handsome, paternal, Christ-like figure purged of any real sexual menace).

The performances of Mick Jagger in Performance and David Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth now stand as grand subversions of the wholesome but bland image of the rock star created by Elvis in his 31 feature films (1956—1969). Elvis might have sung Leiber and Stoller’s “Dirty, Dirty Feeling” to a group of girls on a dude ranch in 1965’s Tickle Me (“It’s Fun!.....It’s Girls!.....It’s Song!.....It’s Color!”) but Jagger and Bowie (and the girls) were “dirty.” By literalizing in their films what Elvis had only sung about in his, Jagger and Bowie forever transformed the image of the rock star, and in so doing transformed rock culture.

Saturday, March 15, 2008

Monday, January 25, 1960: el

According to John Tobler’s book, This Day in Rock: Day by Day Record of Rock’s Biggest News Stories (Carroll & Graf, 1993), Elvis Presley’s first RCA single, Heartbreak Hotel/I Was The One, was released on January 25, 1956--exactly four years earlier than the above date. (Certain web sources proffer a slightly later date, although the discrepancy is minor and ultimately insignificant.)

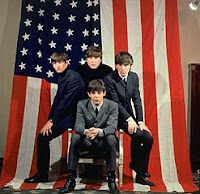

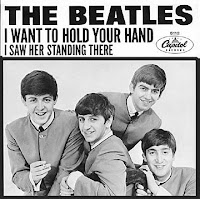

On January 25, 1960, Elvis had just about five weeks left in the Army. No one had yet heard of the Beatles; the band as such didn't exist.  The band that would become the Beatles was still known as The Quarrymen--the band members hadn’t yet decided on the name The Silver Beetles. In a wonderful sort of symmetry, precisely four years later--January 25, 1964--the Beatles first American single, “I Want To Hold Your Hand,” was one week away from becoming the band’s first #1 hit on the American charts, where it would remain perched for almost two months. As everyone knows, 1964 was the annus mirabilis of the Beatles, during which they had nine different singles sharing either the #1 or #2 spot on and off throughout the year. Chart information for 1964 is as follows (courtesy Joel Whitburn, Billboard Top 1000 Singles 1955-1990, Hal Leonard Publishing, 1991):

The band that would become the Beatles was still known as The Quarrymen--the band members hadn’t yet decided on the name The Silver Beetles. In a wonderful sort of symmetry, precisely four years later--January 25, 1964--the Beatles first American single, “I Want To Hold Your Hand,” was one week away from becoming the band’s first #1 hit on the American charts, where it would remain perched for almost two months. As everyone knows, 1964 was the annus mirabilis of the Beatles, during which they had nine different singles sharing either the #1 or #2 spot on and off throughout the year. Chart information for 1964 is as follows (courtesy Joel Whitburn, Billboard Top 1000 Singles 1955-1990, Hal Leonard Publishing, 1991):

Song Title/Peak Date/Peak Position/Weeks at Peak Position

I Want to Hold Your Hand/February 1/#1/7 weeks

Please Please Me/March 14/#2/3 weeks

She Loves You/March 21/#1/2 weeks

Can’t Buy Me Love/April 4/#1/5 weeks

Twist and Shout/April 4/#2/4 weeks

Do You Want To Know a Secret/May 9/#2/1 week

Love Me Do/May 30/#1/1 week

A Hard Day’s Night/August 1/#1/2 weeks

I Feel Fine/Dec. 26/#1/3 weeks

In contrast, Elvis Presley had no songs in the Top 40 in 1964 (or 1965, or 1966, or 1967, or…). It wasn’t until late 1969 that Elvis had another #1 hit, his first big hit in many years. Instead of making records, he was busy making movies. During the years from 1960 (Post-Army, Pre-Beatles) to 1964 (Beatlemania), Elvis made the following movies, released in the following order:

G.I. Blues (1960)

Flaming Star (1960)

Wild in the Country (1961)

Blue Hawaii (1961)

Follow That Dream (1962)

Kid Galahad (1962)

Girls! Girls! Girls! (1962)

It Happened at the World's Fair (1963)

Fun in Acapulco (1963)

Kissin’ Cousins (1964) [Arguably his worst film, the absolute bottom of the barrel, infelicitously released at the onset of Beatlemania]

Viva Las Vegas (1964)

Roustabout (1964)

Hence, while Elvis was preoccupied with his movie career, the Fab Four were becoming one of the most famous bands in popular music history. The criss-cross that occurred in 1964 (one's fortunes up, the other's fortunes down, and I don't mean by fortunes "money") could not have gone unnoticed by either the Beatles or Elvis. In his biography, Elvis (1980) Albert Goldman writes:

No wonder then, that when the Beatles first came to America--welcomed on the Ed Sullivan Show by a telegram wishing them every success and signed by Elvis Presley (though dispatched without his knowledge by Colonel Parker)--Elvis refused point-blank to meet these dubious young men who aspired to the hand of his daughter, the American youth audience. “Hell, I don’t wanna meet them sons o’ bitches!” exploded Elvis when the Colonel ran the proposition by him for the first time during the Beatles’ initial tour in 1964. (Avon Books paperback, 1981, p. 447)

Elvis didn’t meet the Beatles until the third week of August 1965 (the event recounted with different rhetorical flourishes in different biographies) while in Los Angeles filming Paradise, Hawaiian Style (1966), which could be considered his worst film--if it weren't for Kissin' Cousins. He hadn’t been in the recording studio for years, except, of course, for the purpose of recording material for his soundtracks. After the Beatles met Elvis in August, the rest of 1965 worked out as follows:

The Beatles--Rubber Soul (album), December 1965 (U. S.)

Elvis Presley--Harum Scarum (movie), December 1965 (U. S.)

Thus the remark John Lennon made just a few months later, “We’re more popular than Jesus now,” uttered during an interview conducted on March 4, 1966, was made only after he and the other members of the Beatles had met Elvis. Michael Jarrett, in Sound Tracks, A Musical ABC, Vols. 1-3 (Temple University Press, 1998), interprets Lennon’s infamous remark as follows:

When John Lennon declared that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus, what’s the chance that he really meant--in Bible Code--that they were more popular than Elvis? In both Hebrew and the language of rock ‘n’ roll, El means “God.” Lennon, however, couldn’t bring himself to say what he meant. Why? It would have been sacrilegious. Remember, it was Lennon who said, “Before Elvis, there was nothing.” (84)

In other words, Lennon could not bring himself to utter the terrible truth. He could not say, “The Beatles have become more popular than Elvis,” but perhaps, nonetheless, that's what he meant. It’s worth looking at the entire infamous remark Lennon made in 1966, the following quotation taken from Newsoftheodd.com:

When they reached the subject of religion, Lennon said, “Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. … We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first--rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity.”

What if he really meant the following? I have supplied the appropriate substitutions:

Elvis will go. He will vanish and shrink. … We’re more popular than Elvis now; I don’t know which will go first--us or Elvis.

Was Lennon consciously aware of what he really meant?  Could he imagine the improbability that he had displaced his precursor, the one who had, in a very real sense, made him possible in the first place? That he had, figuratively speaking, like Oedipus, committed patricide? What are we to make out of the following juxtaposition, each album representing the first formal studio recordings made by each of the artists subsequent to their August 1965 meeting?

Could he imagine the improbability that he had displaced his precursor, the one who had, in a very real sense, made him possible in the first place? That he had, figuratively speaking, like Oedipus, committed patricide? What are we to make out of the following juxtaposition, each album representing the first formal studio recordings made by each of the artists subsequent to their August 1965 meeting?

The Beatles: Revolver (August 1966)

Elvis Presley: How Great Thou Art (February 1967; recorded 1966 except for "Crying in the Chapel," 1960)

Monday, February 4, 2008

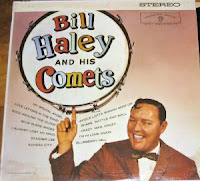

Wednesday, January 13, 1960: Haley's Comet(s)

In yesterday's blog I referred to Albert Goldman's controversial biography Elvis (1981). Having mentioned the book, I was prompted to return to it and re-read the portions relevant to Elvis's army career, and found that, contrary to the general perception many have of the book, Goldman demonstrated a good deal of empathy for Elvis's predicament at the time he was drafted and that he also made some important observations. For instance:

In yesterday's blog I referred to Albert Goldman's controversial biography Elvis (1981). Having mentioned the book, I was prompted to return to it and re-read the portions relevant to Elvis's army career, and found that, contrary to the general perception many have of the book, Goldman demonstrated a good deal of empathy for Elvis's predicament at the time he was drafted and that he also made some important observations. For instance:

For from Elvis's viewpoint, he had nothing to gain from the army and everything to lose. At the time he entered the service, he was at the very peak of his fame. With fads and fashions in pop music changing constantly, with a host of imitators and rivals springing up to steal his stuff, with fame itself such a freaky and chancy thing, what likelihood was there that he could come back two years hence and pick up exactly where he left off? There was none; and, in fact, Elvis never did regain the momentum he lost when he entered the army. So, from Elvis's point of view, his conscription was the worst sort of disaster that could have befallen him as an entertainer and a new star. (324 Avon paperback edition).