A week earlier, on January 2, 1960, then Senator John F. Kennedy announced his candidacy for President of the United States, ending several months of speculation about his intentions. JFK was the first to introduce "speed" into presidential politics, as he was the first presidential candidate to use a private aircraft as his primary means of transportation--"the soaring 60s" indeed (see my blog entry for January 5). According to the page devoted to JFK's airplane at the National Air and Space Museum website, the aircraft was a Convair 240 that had been purchased several months earlier by Joseph Kennedy in preparation for his son's Presidential campaign. According to the NASM webpage:

Historians credit this aircraft with providing Kennedy with the narrow margin of victory for it allowed him to campaign more effectively during that very hotly contested race. The "Caroline," named after President Kennedy's daughter, revolutionized American politics; since 1960 all presidential candidates have used aircraft as their primary means of transportation.

Following his successful bid for President, for security reasons the aircraft was seldom used by JFK afterwards, although it was used by members of the Kennedy family until 1967, when in September of that year Senator Edward Kennedy, recognizing its historical significance, offered to donate the airplane to NASM. Following a formal ceremony in November 1967, the plane was flown to Andrews AFB and then trucked to Silver Hill where it was dismantled and left outside to deteriorate for the next twenty years. In the late 1980s, a curatorial crew and the conservator cleaned the filthy interior of the aircraft, and finally it was moved indoors to safety.

Certain material artifacts of historical significance, such as JFK's Convair 240, have a curious circulation in our culture in their "afterlife." Unlike most quotidian (manufactured) objects, they are transformed into "found objects," capable of being contemplated as works of art, but unlike found objects they often also become excessive signifiers, quasi-magical objects with demonic powers. Think of the myths surrounding James Dean's Porsche 550 Spyder for instance, or the custom-built 1961 Lincoln Continental in which President Kennedy was assassinated. While I could provide many other examples of this sort of fetishization--visit the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame to get an idea of what I'm talking about--this sort of preoccupation is a peculiar characteristic of the so-called "Baby Boom" Generation (of which I am a member), which has detailed and catalogued every last compartment of Baby Boom Culture. While the preservation of such objects serves to connect us in a material way to previous generations, and thus provides the important function of continuity from one generation to the next, the transformation of these manufactured objects into excessive signifiers seems to me to be a recent historical phenomenon, perhaps because the recent hundred years or so seems so characterized by the disaster.

In the Middle Ages, superstitious religious pilgrims often purchased holy relics such as saints' bones, duped by unscrupulous merchants into buying them. The value of the contemporary equivalent of the holy relic is largely determined by that particular object's excessive signification. About a year and a half ago I visited the Titanic exhibit in St. Louis, where a portion of the hull was displayed under plexiglass. A small round hole had been cut into the display, allowing visitors actually to the hull. The hull of the Titanic, JFK's Convair 240, James Dean's Porsche 550 Spyder--even Graceland itself--are all examples of excessive signifiers.

Did I reach through the hole in the plexiglass display and touch the hull of the Titanic? Of course.

Sunday, January 20, 2008

Saturday, January 9, 1960

Monday, January 14, 2008

Friday, January 8, 1960

"...But there ain't no cure for the summertime blues..."

"...But there ain't no cure for the summertime blues..."

According to the webpage www.eddiecochran.info, on January 8, 1960, rocker Eddie Cochran--perhaps most famous for "Summertime Blues"--completed his last formal studio recordings, at Goldstar Studio in Hollywood. The next day, he left for an extended tour of the UK, arriving there on January 10th in order to join up with the Gene Vincent Show. Several popularly successful television performances featuring Cochran and Gene Vincent were broadcast in the UK over the next several weeks.

As is well known, Eddie Cochran never left the UK alive, having been killed slightly over three months after his arrival, the result of an automobile accident that occurred near 12 midnight on April 16th, 1960; he died from his injuries the next afternoon. (I note in passing that author Albert Camus was killed in an automobile accident on January 4, 1960.) In an improbable twist, according to www.eddiecochran.net, the name of the cab driver that fateful night was--George Martin . . . not the George Martin who would later, famously, produce The Beatles, but the serendipity is startling. Perhaps especially so, since one of the earliest known recordings of The Beatles (or, more precisely, three-quarters of the band that would become The Beatles), found on The Beatles' Anthology 1 (1995), is virtually a note-by note copy of Eddie Cochran's "Hallelujah, I Love Her So," recorded by the future Beatles sometime during the spring of 1960.

"Hallelujah, I Love Her So," released in the United States in October 1959, was the last single released in the UK during Cochran's lifetime, released in the UK in January, 1960, no doubt in order to coincide with his UK tour (although I strongly suspect that such extended appearances would not have called "tours" in those days). No doubt John, Paul, or George--or all three--picked up the single sometime soon after its UK release; one strongly suspects that while Cochran didn't appear in concert in Liverpool during his last tour, he made concert appearances (e. g., Manchester) that would not have been impossible for the young lads to attend.

Although John Lennon was always forthcoming about being an Elvis Presley fan, at the time Elvis wasn't doing much recording: he was in the Army--and, on January 8, 1960, Elvis was in Germany, celebrating his 25th birthday. His Army service was coming to an end, but he still had a few weeks left.

Happily, Eddie Cochran was, deservedly so, inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987.

Sunday, January 13, 2008

Thursday, January 7, 1960

"Marina found herself thinking, how odd, that when Khrushchev visited Minsk while she was living there with Lee, there were strong rumors of an assassination attempt."

"Marina found herself thinking, how odd, that when Khrushchev visited Minsk while she was living there with Lee, there were strong rumors of an assassination attempt."

Until the publication of Mailer's book, not much was known about Oswald's time in Minsk, but it is a fascinating tale (indeed, as is Oswald's tale in general), and Mailer devotes almost the first two hundred pages of his book to Oswald in Russia, referencing interviews consisting almost entirely of Oswald's Russian friends.

It was in Minsk, while he was employed there in a factory, that he would meet his future wife, Marina Prusakova, on March 17, 1961 ("...a girl with a French hairdo and red dress with white slippers" wrote Oswald about her in his journal, qtd. on p. 167). If it weren't for the fact that his name is Lee Harvey Oswald, his and Marina's story would by now have formed loosely the basis of a stormy, steamy Hollywood Romance. Having met her in mid-March, by April they are going steady; when she refuses his attempts to seduce her--"to put him off" in colloquial American English--he proposes marriage to her instead--which she accepts. They were married on April 30, 1961, six weeks after they'd met (the picture above was taken in Minsk a month or so after they were married). Marina soon became pregnant, but way before that, Oswald had already decided to return to America.

Of course, Mailer would, I think, caution against "fitting Oswald into one or another species of plot. Perhaps it would be more felicitous to ask: What kind of man was Oswald? Can we feel compassion for his troubles, or will we end by seeing him as a disgorgement from the errors of the cosmos, a monster?" (p. 197). Has any modern historical figure been the subject of so much speculation? Has any figure been so carefully studied, had so much written about him, had so many narrative emplotments constructed, so many hundreds of details scrutinized and re-scrutinized, as Lee Harvey Oswald? I have no idea of the number of websites devoted to Oswald and Kennedy assassination conspiracies, but they must number in the dozens. I'm not a believer in the conspiracy theories, all of which, as is well known, received renewed interest after Oliver Stone's JFK (1991). I for one think Mailer is right: rather than ask, Who killed John F. Kennedy? the more difficult and more daunting question is, What kind of man was Oswald?

"Who among us can say that he [Oswald] is in no way related to our own dream?" Mailer asks at the end of his long and disturbing mystery (p. 791), a reminder to us that the Other is not entirely different than ourselves. And as the story of Lee Harvey Oswald also reminds us, some mysteries are even more disturbing to us because they have no reassuring answers, no comforting revelations.

Saturday, January 12, 2008

Wednesday, January 6, 1960

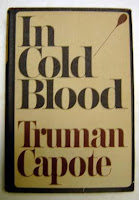

"Until one morning in mid-November of 1959, few Americans--in fact, few Kansans--had ever heard of Holcomb."

On January 6, 1960, Richard Hickok and Perry Smith were returned from Nevada to Finney County in Western Kansas, in order to stand trial for the murders of the Clutter family in mid-November, 1959: the parents, Herb and Bonnie, and two of their younger children still living with them, Nancy and Kenyon. The return of Hickok and Smith to the place of the murders was depicted in the film Capote (2005), with future In Cold Blood author Truman Capote (wonderfully played by Philip Seymour Hoffman), by then having traveled to Kansas and researching the case, witnessing the event.

Six months earlier, on June 25, 1959, Charles Starkweather was executed by electric chair by the State of Nebraska. I had turned five years old a couple of days earlier. I don't remember anything about Starkweather's execution, although it happened just up the highway. I have a vague memory of staying overnight with my grandparents during his murder spree which, in January 1960, would have happened a couple of years earlier. The reason I remember the historic moment at all was because at bedtime my grandmother asked my grandfather if he'd locked the doors--the first time in my life I remember anyone ordering the doors of the house to be locked. Later--perhaps the next day, I don't recall--I asked my mother why granny and grandad had locked the doors, and she explained it to me: a killer was on the loose, he could show up anywhere. At the time, we lived about forty miles from Lincoln, where Charles Starkweather's murder spree had begun. Whether the doors of our house continued to be locked after Starkweather was arrested I do not know.

Over two decades later, in 1986, I was living in Lincoln, Nebraska, where I'd been living since 1979. My wife and I locked the doors at night. Was that habit instilled in us by the likes of Charles Starkweather, Richard Hickok and Perry Smith? Or by family habits with which we'd grown up? I do not know. One hot day that summer, my next door neighbor asked me if I'd like to see Charles Starkweather's grave, and I said yes. A good friend of his was a gravedigger at Wyuka Cemetery, located on the north side of Lincoln's O Street between 33rd and 48th Streets, and recently he had shown my neighbor the grave site. On the arranged day, we drove to the cemetery, between five and ten minutes from my home. You have to know where his grave is in order to find it, as the small rectangular stone, inscribed only with the name Starkweather, rests flat on the ground in the shade of a large tree (at least at the time), just a few steps from the road.

On the day we visited--and this is a true story--we discovered that someone had left a small bouquet of flowers on top of the gravestone. Serendipitously, it must have been around the 25th of June--that day, or one or two on either side. Seeing those flowers on the gravestone instantaneously connected me to my past and invoked all the memories associated with Charles Starkweather, not only those when I was a small boy, but those from years later, in 1976, when his putative accomplice at the time of killings, Carol Fugate, was, controversially, released from the Nebraska State Prison in Lincoln.

Despite the historic proximity of the murders, and despite the fact that both cases featured the Midwestern outlaw couple (as in "Bonnie and Clyde"), the crucial difference between the two murder cases is, of course, Truman Capote: Starkweather never had the literary equivalent of Capote, while Hickok and Perry did. The style of writing known as "New Journalism" grew out of In Cold Blood, while in contrast, because his story had no prestigious literary antecedent, Starkweather's story, devoid of the compelling, if not sympathetic psychological portrait created by Capote, became, in its filmic incarnations, more "sensational," the killer more incoherent, more of a "bad seed" rather than portrayed as a consequence of his environment.

Friday, January 11, 2008

Tuesday, January 5, 1960

"A nationwide poll of your hopes, plans and fears for the decade ahead, with picture reports on the mood of the American people as they enter THE SOARING ‘60’s."

As the cover of the January 5, 1960 Look magazine reveals, the mass media's role to promulgate the government’s agenda is so obvious it stares you right in the face. (The X Files' tag line, "The Truth is Out There," is in fact very true--it's right in front of you.) After the Soviet Union’s successful launch of Sputnik I on October 4, 1957, the so-called Space Age began.

Translation: the U.S. government convinced the American public that the Soviets’ ability to launch satellites meant they had the technology to launch ballistic missiles, that is, long-range rockets with nuclear bombs. A threshold moment, a new relationship between the government (military) and educational institutions (science and technology) began. Sputnik prompted Congress, in July 1958, to pass the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as of October 1, 1958. In January 1960, 50% of the government’s total budget was devoted to defense. The cover of Look associates the space program and a rocket's nighttime take-off with the promise, mystery, and anxiety of the new decade. Ironically, the word "soaring," associated with "flying" and being "high," anticipated the language of the drug experience--"tripping"--popularly associated with the 1960s. (See the January 1 blog entry.)

Translation: the U.S. government convinced the American public that the Soviets’ ability to launch satellites meant they had the technology to launch ballistic missiles, that is, long-range rockets with nuclear bombs. A threshold moment, a new relationship between the government (military) and educational institutions (science and technology) began. Sputnik prompted Congress, in July 1958, to pass the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as of October 1, 1958. In January 1960, 50% of the government’s total budget was devoted to defense. The cover of Look associates the space program and a rocket's nighttime take-off with the promise, mystery, and anxiety of the new decade. Ironically, the word "soaring," associated with "flying" and being "high," anticipated the language of the drug experience--"tripping"--popularly associated with the 1960s. (See the January 1 blog entry.)In the media, ever fond of the sound bite, the Space Age soon became the Space Race, figuratively transforming what was originally a wholesale institutional restructuring (new jobs, job incentives, re-defined job relationships, job responsibilities, new administrative duties, new budgets, budget sources and amounts of funding, re-defined institutional objectives, on and on) into a competitive sporting event with the Soviet Union.

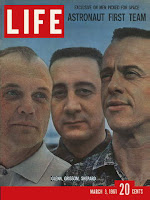

By means of the national media, neologisms such as “astronauts,” references to “flight teams,” acronyms such as NASA, rocket types associated with military bases such as Redstone, and mythological (divinely sanctioned) designations such as “Mercury” and “Gemini” all allowed military and quasi-military terminology to become part of the language of daily life. During the 1960s, Life magazine—alone—dedicated over three-dozen covers to the space program (the cover of the March 3, 1961 issue is above left), although it is hard to tally the number of hours of television programming that was devoted to launches, orbital flights, moon flights, and so on. A new, very modern sort of hero was born, characterized, some years later, by Tom Wolfe, as having "the right stuff." Since "astronauts" were no longer (military) pilots in the traditional sense, their character had to be redefined anew.

By means of the national media, neologisms such as “astronauts,” references to “flight teams,” acronyms such as NASA, rocket types associated with military bases such as Redstone, and mythological (divinely sanctioned) designations such as “Mercury” and “Gemini” all allowed military and quasi-military terminology to become part of the language of daily life. During the 1960s, Life magazine—alone—dedicated over three-dozen covers to the space program (the cover of the March 3, 1961 issue is above left), although it is hard to tally the number of hours of television programming that was devoted to launches, orbital flights, moon flights, and so on. A new, very modern sort of hero was born, characterized, some years later, by Tom Wolfe, as having "the right stuff." Since "astronauts" were no longer (military) pilots in the traditional sense, their character had to be redefined anew.

Tuesday, January 8, 2008

Monday, January 4, 1960

"Out in the west Texas town of El Paso, I fell in love with a Mexican girl..."

According to Billboard Top 1000 Singles 1955-1990 (Hal Leonard Publishing, 1991) Marty Robbins’ “El Paso” was the “Number 1” single in the United States for two weeks beginning the week of January 4. “El Paso” is indebted to the corrido (a narrative song, often a ballad, sometimes with a rhythm much like that of a waltz) that Robbins transformed into a country-western ballad. It told the story of a cowboy who fell in love with a Mexican cantina dancer (her name is not important). She was wicked, though, and mocked his love by flirting with other cowboys. One night, so the narrator tells us, in a jealous rage, he shot and killed a boy to whom the girl was being overly attentive. The cowboy fled El Paso, but soon realized that his love for her was stronger than his fear of death, and he returned. He was set upon by the vengeful friends of his victim, and was mortally shot by them. He dies, seemingly happy, in the feckless girl’s arms. He died exalted because of his passion, and yet his passion remained unfulfilled, and thus his desire brought him not ecstasy, but death.

Another pair of famous lovers, Romeo and Juliet, who had only a few days to celebrate their passion--after all, they met on Sunday and died on Thursday, and had just one blissful night of erotic pleasure together--and whose love ended in mutual suicide, are nonetheless celebrated as the happiest and most famous lovers in the western world. Paradoxically, the brevity and misery of their fated love is touted as the model to which lovers should aspire. For love to be genuine, it has to be autonomous, intense--and calamitous. On the one hand, our myths uphold the idea of living happily ever after, but on the other, we measure authentic love only by the degree to which it incites misery and suffering. Denis De Rougemont, in Love in the Western World, says that obsessive passion is really the desire for death: Isn't that the lesson "El Paso" teaches us? In order for love to be real and authentic, we must be unhappy. In one of those delicious ironies possible only in art and not life, “El Paso” was covered by none other than...The Grateful Dead, who played the song in concert several hundred times. Perhaps Bob Weir, or Jerry Garcia, or both, knew what the song was really about.

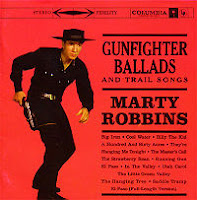

Marty Robbins’ Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, released in September 1959, was one of the very first LP records I remember (as opposed to 7" 45s and my parents' 78s). Holding the cover in my hands,

I would study the cover, flipping it back and forth, first the cover, then the back, examining every detail, reading every word. And I would play the record over and over and over. My mother was very tolerant. I was fascinated by it—and still am. The songs are remarkably diverse, each one a narrative in miniature; they were about religious conversion, Fate, Destiny, Love, and Death, filled with unexpected reversals, catastrophic endings. I now own it on CD. Robbins, gifted with a beautiful, remarkably expressive voice, was a mystic who died prematurely in 1982 at age 57.

I would study the cover, flipping it back and forth, first the cover, then the back, examining every detail, reading every word. And I would play the record over and over and over. My mother was very tolerant. I was fascinated by it—and still am. The songs are remarkably diverse, each one a narrative in miniature; they were about religious conversion, Fate, Destiny, Love, and Death, filled with unexpected reversals, catastrophic endings. I now own it on CD. Robbins, gifted with a beautiful, remarkably expressive voice, was a mystic who died prematurely in 1982 at age 57.In 1976, a few years before his death, Robbins revisited “El Paso” with a song titled “El Paso City.” The narrator is a passenger on an airplane flying over the west Texas desert, near El Paso, who remembers a song he’d heard long ago—“El Paso.” The narrator experiences an anamnesis (a sudden remembering of something he’d forgotten he'd forgotten) and asks, “Could it be that I could be/the cowboy in this mystery/That died there in that desert sand so long ago,” which I’ve always interpreted as Robbins’ admission that he believed he was, in fact, in his previous life the doomed cowboy he wrote about in the earlier song. Of course, in exploring his relationship with the muse that resided within him, "El Paso City" is also about the mystery of artistic creation.

And of course, "El Paso" is not about the real place, the Texas border town. In its figurative sense, "El Paso" names a certain imaginary location, a border kingdom where Desire and Obsession meet Death. In El Paso, you can find the answer to the daunting riddle, Why is passion so strongly linked with death?