The collocation “Desert Island Discs”—DIDs— normally refers to a music critic’s list of revered recordings, usually consisting of ten (10) albums, as in Top 10. The term is derived from the question, “If you were stranded on a desert island, what ten albums (normally ten, out of respect to the commandments), out of all the albums you own, would you want to have with you?” Given the hypothetical nature of the question, it might just as easily be phrased as, “If your house were on fire, what ten albums would you grab on the way out?” Implicit in the question is the assumption that the critic compiling the list has hoarded, in a grossly materialistic way, more albums than he could ever possibly listen to (or rather, listen to carefully). Actually, the compilation of a “DIDs” list is a tacit admission by the critic that he really listens only to a small portion of the many hundreds (or thousands) he owns.

The collocation “Desert Island Discs”—DIDs— normally refers to a music critic’s list of revered recordings, usually consisting of ten (10) albums, as in Top 10. The term is derived from the question, “If you were stranded on a desert island, what ten albums (normally ten, out of respect to the commandments), out of all the albums you own, would you want to have with you?” Given the hypothetical nature of the question, it might just as easily be phrased as, “If your house were on fire, what ten albums would you grab on the way out?” Implicit in the question is the assumption that the critic compiling the list has hoarded, in a grossly materialistic way, more albums than he could ever possibly listen to (or rather, listen to carefully). Actually, the compilation of a “DIDs” list is a tacit admission by the critic that he really listens only to a small portion of the many hundreds (or thousands) he owns.

I vividly remember a conversation I had about ten years ago or so with my friend Mike Jarrett, a music critic himself and a world expert on jazz, when the topic of DIDs came up. In the context of a conversation regarding what each of us might include on a DIDs list, he paused to ask me a question that he prefaced by insisting he was asking in all seriousness. Of course, I said, ask it. Why would I think you were not asking a serious question? The question was this, brilliant really, which I’ve pondered many times in the years since: What makes up God’s record collection: Every record ever made, or just the best records ever made?

You don’t have to have any sort of conventional religious belief--even none--to answer the question. How do you answer it--not in a “theoretical” way, meaning, how “would” you answer it assuming the off-chance that someone ever asked you--but how do you? Does the most ideal of album collections in God’s place consist of all the albums ever made, or only the best (however the Almighty should decide that)? Is heaven (a desert island, of the tropical paradise sort) a place of plenty, of excess, of everything, or is it premised on the Puritan Principle of Parsimony—that is, DIDs. (When you go to heaven, in other words, and you’ve got only ten choices, what shall they be?) Is it all-inclusive, or exclusive? If you had your druthers, do you invite everybody, or only a select few? Certain Christian traditions, of course, tell us that those selected are an elite few—the Chosen. But I recall answering Mike’s question, “all of them. God has all of them.” Mike’s response was, “But does He listen to them all?” Isn’t this the real paradox of desire: Is desire polymorphously perverse (indiscriminate), or fetishistically perverse (rarified)?

I have never seen a list of DIDs that was really anything more than a particular critic’s fetishized list, selected from a standardized list of “Rock Greats”—the critic’s favorite Beatles album, favorite Rolling Stones album, favorite Pink Floyd album, Led Zeppelin album, Bob Dylan album—you get the idea. And outside of some occasional, unexpected flourishes—Cream, perhaps, or U2, Grateful Dead, Nirvana—the list never contains surprises. (Or, if it does, it’s the “Guilty Pleasure” sort, that is, the fetishized sort, meaning the critic "can’t explain it," "just likes it" sort, meaning it eludes rational explication--he’s a mystery even to himself.) In other words, we all know the critical darlings that are going to be there—Rock music’s Great Tradition—the suspense is simply finding out which album by the canonical bands happens to be the critic’s favorite (at the moment).

The problem is that many music critics are really just fans who’ve learned how to write and found a forum to expound from, fans in the sense that their judgment is uncritical—everything by the band (Beatles, Pink Floyd, fill in the blank) is great. Every song, every album, every note by the band is just as good as every other one. Now this just can’t be true--or can it?

By way of analogy, think of the work by a major literary figure—Shakespeare, for example. As Harold Bloom points out—Bloom being one of America’s best critics—had Shakespeare died at the same age as his contemporary, playwright Christopher Marlowe, and Marlowe lived on instead, Marlowe would have been considered historically the greater playwright. Shakespeare’s early plays do not have the level of sophistication and craft of Marlowe’s early plays. At a younger age, the fact is, Marlowe was the stronger playwright of the two. Of course, history is radically contingent: Marlowe was murdered, and Shakespeare lived, eventually composing the great tragedies upon which his reputation largely, and justly, rests. Likewise, of all the many volumes of his writings, the crucial importance of British poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge (author of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner) rests, according to Bloom, on a mere nine poems—but what a brilliant nine they are. In popular music criticism, most critics refuse to make such keen discriminations, partly because they are afraid history will prove them wrong, and so overestimate the importance of every album ("five stars"), or else invent an ad hoc system on which to base their judgment--yet another mechanism of desire--which is presented as “objective.”

Question: Is Meet the Beatles as good a record as the White Album? Or, alternatively: Does God have all the Beatles albums, are only the very best?

Some, rightly so, will cry foul and claim a category error: first I asked about records, and then I asked about albums. In an earlier post, I claimed the two were not the same, a record being a material artifact, an album a concept. But if an album is a concept, does God, then, prefer "Greatest Hits" packages, or the individual albums, in the sense of particular records? Example: Does God have The Eagles' Hotel California, or The Eagles' Greatest Hits? Or all of the individual albums, avoiding the Greatest Hits?

Thursday, March 27, 2008

DIDs: Of Records, Albums, and Theology

Monday, March 24, 2008

Thursday, January 28, 1960: Why Are There Lyrics, Anyway?

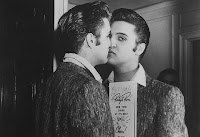

Four years earlier than the above date, in his first national television appearance on the Dorsey Brothers’ Stage Show, broadcast January 28 1956, Elvis Presley chose to open with “Shake, Rattle, and Roll,” a song that Frank Sinatra, for one, would never have condescended to perform. Sinatra probably snorted in derision at Elvis’s second song that evening, too: “Flip, Flop & Fly.” Three months later, when Elvis again appeared on the Stage Show, he sang “Tutti Frutti.” Forget what young females thought about Elvis’s bad boy sneer, his gyrating hips, his wiggling and shimmying, his clamorous shouts and erotic moans—that’s legendary. The more important question is, why did Elvis choose to perform, on a national stage, such “nonsensical” songs?

Four years earlier than the above date, in his first national television appearance on the Dorsey Brothers’ Stage Show, broadcast January 28 1956, Elvis Presley chose to open with “Shake, Rattle, and Roll,” a song that Frank Sinatra, for one, would never have condescended to perform. Sinatra probably snorted in derision at Elvis’s second song that evening, too: “Flip, Flop & Fly.” Three months later, when Elvis again appeared on the Stage Show, he sang “Tutti Frutti.” Forget what young females thought about Elvis’s bad boy sneer, his gyrating hips, his wiggling and shimmying, his clamorous shouts and erotic moans—that’s legendary. The more important question is, why did Elvis choose to perform, on a national stage, such “nonsensical” songs?

One of the reasons Elvis was derided early on was that his choice of material seemed so ludicrous: “Flip Flop & Fly”? “Tutti Frutti”? Why not the deep yearning of classic ballads such as “In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning” or “When Your Lover Has Gone”? Why choose songs that are so devoid of substance—so apparently trivial? Why not perform the old standards instead? Frank Sinatra was so incensed by Elvis’s music that he wrote a magazine article condemning rock as “the most brutal, ugly, degenerate, vicious form of expression it has been my displeasure to hear.” He averred that rock ‘n’ roll is “sung, played, and written for the most part by cretinous goons and by means of its almost imbecilic reiterations and sly, lewd—in plain fact—dirty lyrics, it manages to be the martial music of every sideburned delinquent on the face of the earth.” (qtd. from Kitty Kelley, His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra, Bantam Books, p. 277).

However, according to Donald Clarke, by the time Elvis appeared on the historical scene, the music business wasn’t the same as it had been when Sinatra began his career slightly over a decade earlier. By the early 1950s, “good white songs were becoming scarce. The Berlins, Gershwins and the rest had died or retired, and the classic songs they had written could not be imitated.” Hence, Elvis never had access to the sort of material to which Sinatra had access (“standards”), and perhaps that made all the difference. (As a corollary, Elvis was never offered the sort of strong dramatic roles in movies that Sinatra was offered, either.) The composers of many of Elvis’s early songs were black, who were writing for the black music market, and who had a different sensibility than the Berlins and Gershwins. So, in answer to the question as to why Elvis chose to perform songs such as “Flip Flop & Fly” and “Tutti Frutti,” the reason is because Elvis chose songs that didn’t sound like anything else. But to Frank Sinatra, if songs weren’t standards, they were aberrations.

Simon Frith offers a way of understanding the difference between Sinatra and Elvis by referring to Dave Laing’s book, Buddy Holly (1972). Laing says that those interested in understanding rock music need to have the musical equivalent of film studies’ distinction between the auteur and the metteur en scene. According to Laing:

The musical equivalent of the metteur en scene is the performer who regards a song as an actor does his part—as something to be expressed, something to get across . . . . The vocal style of the singer is determined almost entirely by the emotional connotations of the words.

Frank Sinatra, then, was the musical equivalent of the metteur en scene. In contrast, says Laing, the rock auteur

is determined not by the unique features of the song but by his personal style, the ensemble of vocal effects that characterize the whole body his work.

Elvis, then, was the equivalent of an auteur: the meaning of the song is not simply organized around the words, but rather in the exceptional nature of his singing style. Sinatra condemned Elvis because he didn’t understand his music, nor could he, at the time, quite grasp the historic rupture in American popular music that Elvis represented. In film historical terms, Sinatra was the old, “classical” Hollywood, while Elvis anticipated the age—our age—of the independent film, the age of the auteur.

Sunday, March 23, 2008

Mondegreen Pt. 3: Melon Calling Baby

Although there are rather sophisticated Site Meter services available for monitoring website traffic, I use only the “basic” service—in other words, the free one. Other than page views, I don’t pay any attention to the various sorts of traffic data available to me—this isn’t a commercial site, after all, so such information is not critically important to me. The other day, however, I decided to take a look at the data as listed in the category “By Referrals,” information on how one’s particular website is found by a particular viewer other than by directly entering the specific URL (that is, data on re-directed traffic).

Although there are rather sophisticated Site Meter services available for monitoring website traffic, I use only the “basic” service—in other words, the free one. Other than page views, I don’t pay any attention to the various sorts of traffic data available to me—this isn’t a commercial site, after all, so such information is not critically important to me. The other day, however, I decided to take a look at the data as listed in the category “By Referrals,” information on how one’s particular website is found by a particular viewer other than by directly entering the specific URL (that is, data on re-directed traffic).

I was mildly astonished to discover how many individuals had been directed to my blogspot as a consequence of searching the key words, “Betty and the Jets lyrics.” The reason for this is that a few blog entries ago I wrote a blog entry on the mondegreen, “Dead Ants Are My Friends, A-Blowin’ in the Wind,” followed a few days later by a second entry, a follow-up that I’d titled, as a jape, “Betty and the Jets.”

After learning how many page visits my blogspot had received as a consequence of individuals searching for the lyrics to “Betty and the Jets,” I felt a tad bit guilty: wasn’t I perpetuating what is clearly a rather widespread misunderstanding, adding to, rather than clarifying, the essential homophonic ambiguity regarding “Bennie and the Jets” by disseminating the deformed, mondegreen version, “Betty and the Jets”? On the other hand, I decided, perhaps having read about the mondegreen, the searchers might, in a sort of roundabout way, figure out the song’s actual title, and hence find the lyrics they had set out to find.

In my earlier “Betty and the Jets” blog entry, I’d suggested the existence of the mondegreen, at least insofar as lyrics are concerned, is a consequence of a message being deformed once it is subject to electronic transmission, a technology which emphasizes the received nature of messages.

But perhaps on this Easter Sunday, we might want to consider an entirely different theoretical issue, that of the (invisible) effect of homophonic ambiguity (the mondegreen) on the transmission of messages that were originally made within a largely oral (that is, largely illiterate) culture, and consider whether the transmission of Biblical texts might also have been subject to deformation by the mondegreen. I’m sure such a possibility has given many a Biblical scholar a sleepless night or two (or three). I know it has been exploited for comic effect: think, for instance, of Monty Python’s Life of Brian, and the line, "Blessed are the cheesemakers," although this is an example of an intentional deformation, not an unintentional one, as is the mondegreen. However, the point is clear enough.

There is certainly textual evidence that serves as a sort of “smoking gun” for the existence of the Biblical mondegreen, as Frank Kermode has astutely pointed out in his fascinating book, The Genesis of Secrecy. In his discussion of figura (i.e., typology, a method of Biblical interpretation premised on the assumption that events in the New Testament are “pre-figured,” or anticipated, by textual material found in the Old Testament), Kermode discusses the evidence that Old Testament texts were sometimes “christologized,” that is, “rewritten in a more convenient form.” He writes:

A famous instance is the Christian version of Psalms 96:10, as found in Justin, where the words “from the tree” are added to the original text, “The Lord has reigned.” (107)

The footnote Kermode adds to this passage is worth looking at in detail:

I have heard this example contested on the ground that we cannot be sure there were not Septuagint manuscripts that included the words apo tou xulou (“from the tree”). An explanation of how such an intrusive reading might have come about is this: a translator, coming across the Hebrew word selah, which, though it is not infrequent in the Psalms, has no certain meaning, transliterated it into Greek xela or even xyla, so that the text read “The Lord shall reign xyla.” The addition was modified to xylou, and somebody then made sense of it by inserting apo and reading apo xulou, “from the tree”—thus “manufacturing a prophecy of the crucifixion which was to be welcomed by Christian exegetes” . . . . (158-59).

In other words, the actual text was modified by the exegete’s desire for the New Testament to fulfill the promises of the Old Testament. The analogy, of course, is that one hears what one wants to hear. True, Kermode’s specific example is one of scribal corruption of the orthographic sort (orthography concerns spelling, but also the issue of how sounds are expressed by written symbols), but it is only one of the many kinds of ambiguity in language. Some words have one sound but multiple spellings, with different meanings for each spelling (e.g., main/mane), homophones in the strict sense. But there are words that have one spelling but have multiple meanings (e.g., “bank,” as in river bank, but also “bank” as in financial institution) called polysemous words. Obviously, both kinds of words can confuse listeners. In Kermode’s example, the argument for the addition of “from the tree” is based on the assumption that some ancient redactor, confused by the Hebrew word selah, decided it was a pseudohomophone (for a contemporary example, for instance, think of the use of “luv” for “love”) and therefore made an orthographic error, substituting either the Greek word xela or possibly xyla. A subsequent redactor then modified xela/xyla to xylou, creating yet another confusion, one subsequently resolved by yet another redactor, the later one adding of the word apo and reading apo xulou, “from the tree.” Note the progressive deformation caused by the original substitution.

There’s a famous example in the history of literary criticism of a scholarly article having been written based on a text that had an error of the orthographic kind. The literary scholar in question (nameless) wrote a long, involved interpretation of the profound religious and metaphysical implications of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, mistakenly basing his interpretation on a textual source in which the phrase, “soiled fish of the sea” was, unknown to the critic, a corruption of the phrase found in the first and early editions of the novel, “coiled fish of the sea.” (“Soiled fish” vaguely suggesting of the idea of original sin, while “coiled fish” suggesting the meaning of the Old English “wyrm,” a serpent or dragon, and hence the Devil.) How easily some later copy-editor could have made such a mistake; how seemingly minor such a simple substitution of the glyph “s” for the glyph “c”—but how astonishing the interpretive flight made possible by such a seemingly insignificant error!

I’ve made the same sort of mistake myself. I am one of those listeners who for years thought Bob Dylan sang, in “Tangled Up in Blue,”

Split up on the docks that night

rather than the lyric as published on his website:

Split up on a dark sad night

Obviously, my interpretation of the song had always rested, in part, on mishearing this particular lyric. I still prefer my version over the actual lyric (the role of desire in hearing). That the song’s narrator and the unnamed woman “split up on the docks that night” always had a wonderfully cinematic, mysterious quality to it: a foggy, dockside scene in chiaroscuro, two figures in silhouette, illuminated from behind by a single bulb beneath a metal canopy overhanging the entrance to some small, dilapidated shack, with the small squibs of light marking the portholes of the docked ships behind them. I thought it was a suitably romantic image for such a somber parting. How non-cinematic is the actual lyric (to me), but the point is how one’s interpretation rests on how one has decoded the message.

And just think, all this time, you wanted to be a rockin’ polestar? Or how about a rockin' pollster? Examine not the boat in your neighbor's eye, remove the bead from your own!

Saturday, March 22, 2008

Tuesday, January 26, 1960: Alien Sex

One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh...

One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh...

Having turned 25 years old in January, 1960, Elvis would have turned 73 years old in January of this year. Sharing the same birthday as Elvis, January 8, David Bowie turned 61 a couple of months ago (having turned 13 years old in January, 1960). In a few more months, Mick Jagger will be 65. (Astonishingly, Bill Wyman of the Stones already celebrated his 71st birthday.) In the history of rock ‘n’ roll, eventually it may come to pass that British artists such as Jagger and Bowie will be perceived as more provocative rock stars than Elvis Presley, although Elvis in a very real sense created them, that is, made them both possible, enabling their later elaborations on the image of the (white) rock star he pioneered.

One reason for this eventuality may be that both Bowie and Jagger were willing to experiment with their masculine image much more than Elvis. Although extraordinarily erotic to a generation of young women, Elvis never tried any such experimentation--it probably never occurred to him. What this difference suggests, among other things, is that Bowie’s and Jagger’s particular allure is not Elvis’s—and never was. Critic Greil Marcus has argued that what Elvis did was to purge the Sunday morning sobriety from folk and country music and expunge the dread from the blues. In doing so, he transformed a regional music into a national music, and in doing so invented party music. Elvis popularized an amalgam of musical forms and styles into “rock ‘n’ roll,” a black American euphemism for sexual intercourse. What the Rolling Stones did to rock music (and Bowie after them) some years after Elvis made sex an integral part of rock music’s appeal, was to infuse rock with a bohemian theatricality, at first through the key figure of Brian Jones, who was the first British pop star to cultivate actively a flamboyant, androgynous image. For a time, Jones even found his female double in Anita Pallenberg. Brian Jones and the Stones thus re-introduced into rock music its erotic allure, and hence made it threatening (again).

History will recognize that the cultivated androgyny and transvestitism of 1960s rock stars such as Jagger and Bowie destabilized and subverted stable categories of the self and sexual identity, which is why as cultural practices they were perceived by some as so threatening and so subversive to genteel, bourgeois culture. (Indeed, Brian Jones seems to have had deep disdain for middle-class puritanism and sexuality morality.) By the late 1960s and early 1970s, roughly four decades ago, rock music had become synonymous with decadence. The connection was cemented when Mick Jagger appeared in Donald Cammell and Nic Roeg’s Performance (1970) as a bohemian rock star living in a ménage à trois with two women--one of whom was Anita Pallenberg. A few years later, in 1976, David Bowie appeared as a sexually ambiguous alien, Thomas Jerome Newton, in The Man Who Fell to Earth (although, as David Cammell recently told me, Peter O'Toole was first considered for the part of Newton.) The Bowie character was similar to the Michael Rennie character (Klaatu, aka “Mr. Carpenter”) in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) by virtue of his possessing advanced technology. But he was utterly unlike the Rennie character in that his alien sexuality was foregrounded; it was essential to defining his difference. (Michael Rennie is to The Day the Earth Stood Still what Elvis Presley is, now, to rock culture—a benign, handsome, paternal, Christ-like figure purged of any real sexual menace).

The performances of Mick Jagger in Performance and David Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth now stand as grand subversions of the wholesome but bland image of the rock star created by Elvis in his 31 feature films (1956—1969). Elvis might have sung Leiber and Stoller’s “Dirty, Dirty Feeling” to a group of girls on a dude ranch in 1965’s Tickle Me (“It’s Fun!.....It’s Girls!.....It’s Song!.....It’s Color!”) but Jagger and Bowie (and the girls) were “dirty.” By literalizing in their films what Elvis had only sung about in his, Jagger and Bowie forever transformed the image of the rock star, and in so doing transformed rock culture.

Thursday, March 20, 2008

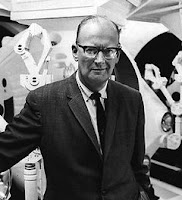

Arthur C. Clarke, 1917-2008

Most certainly 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) made Arthur C. Clarke the most famous science fiction writer in the world. I’m not claiming that he was the best nor even the greatest—although for many he is the very epitome of the SF writer—but unquestionably he was the most famous, a simple matter of fact. His closest rival in that regard may be Ray Bradbury. My personal tastes gravitate toward SF authors such as Philip K. Dick and J. G. Ballard, but it was the writing of Arthur C. Clarke that initially drew me to science fiction decades ago.

Most certainly 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) made Arthur C. Clarke the most famous science fiction writer in the world. I’m not claiming that he was the best nor even the greatest—although for many he is the very epitome of the SF writer—but unquestionably he was the most famous, a simple matter of fact. His closest rival in that regard may be Ray Bradbury. My personal tastes gravitate toward SF authors such as Philip K. Dick and J. G. Ballard, but it was the writing of Arthur C. Clarke that initially drew me to science fiction decades ago.

When I first saw 2001: A Space Odyssey, I was at the impressionable age of fourteen. As everyone knows, although the one sheet of 2001: A Space Odyssey promoted the film as a Cinerama presentation, it wasn’t, of course, projected in movie theaters in true Cinerama. But for me that’s a moot point, anyway, because I didn’t see it in Super Panavision 70, what MGM was then calling Cinerama; in fact, I never have seen it in that format--and never will. I first saw it at the drive-in, of all places, and, subsequently, in the years after, during its re-release, in 35mm prints. And yet despite the less than ideal venue in which I first saw it, the film so profoundly captured my imagination that I subsequently went back to see it again, perhaps five or six times. What did I care whether it was at the drive-in? I would have gone to see it anywhere. Its power is not simply in its images, but in its ideas--and its music.

The soundtrack to 2001 became the first album I ever purchased (with my own money). I had saved up my allowance, and of all the albums on the racks—albums by the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Association, Vanilla Fudge, Tommy James and the Shondells, Steppenwolf, Jimi Hendrix, on and on and on—the album about which I carefully deliberated, and eventually selected, was the soundtrack to 2001. I have that album to this day, and, alas, it has all of the tell-tale signs of age, e.g., “cover wear,” “corner dings,” “seam splits, “surface markings on record,” etc. Assuming my home is never subject some catastrophic event—fire, explosion, lightning, aircraft damage—I always will own it, until the day when my heirs are left to dispose of it, an antiquated, tattered material artifact connected to some decades-old movie.

Having read the novelization of 2001: A Space Odyssey around age fifteen, I was compelled to find more work by its author. My high school library had a few of Clarke's books; of those I read, I remember very much liking Islands in the Sky. A juvenile novel, I remember it being about a boy living on a space station, where human problems take second place in a world in which the imaginative reach of science was boundless. Soon after, I came across a few of Clarke’s short stories in some SF anthologies that I purchased off the carousel book rack at Garvey’s Rexall Drugs store.  In due time Jerome Agel’s The Making of Kubrick’s 2001 (Signet, 1970) was published in paperback, followed a couple of years later by the book I found even more interesting, Clarke’s The Lost Worlds of 2001 (Signet, 1972), a detailed account of the making of 2001 that had the virtue of including Clarke’s short story “The Sentinel” (primary source for the film), as well as alternative script material that wasn’t used in the finished film.

In due time Jerome Agel’s The Making of Kubrick’s 2001 (Signet, 1970) was published in paperback, followed a couple of years later by the book I found even more interesting, Clarke’s The Lost Worlds of 2001 (Signet, 1972), a detailed account of the making of 2001 that had the virtue of including Clarke’s short story “The Sentinel” (primary source for the film), as well as alternative script material that wasn’t used in the finished film.

I was a freshman in college, though, when I first read Childhood’s End, the novel that, for me, is the great Arthur C. Clarke novel. In the many years since I’ve become a college English teacher, I’ve taught it whenever I’ve had the opportunity to teach a course in science fiction. Childhood’s End employs the idea Clarke had first used in “The Sentinel” (and hence, subsequently, in 2001) in which humankind achieves transcendence under the tutelage of benevolent but inscrutable aliens—which in the case of Childhood’s End happen to have a strong resemblance to the Devil (vaguely reptilian, with horns and tail). I choose to think Clarke never abandoned the fundamental premise of American writer Charles Fort (1874-1932). Fort, a student of the paranormal and strange and unusual phenomena, postulated the utterly paranoid idea, “We are property,” meaning that the earth and its inhabitants are the playthings of unknown but immensely intelligent creatures from outer space. I’m not aware of any criticism that has been written about 2001: A Space Odyssey that explores the way in which it is a Fortean film.  Fort’s assertion that “We are property” is the unstated premise of “The Sentinel,” as it is for 2001. As it turns out, many years later, in one of those unexpected turns of which life consists, as part of the research for the book I co-authored with Rebecca Umland, Donald Cammell: A Life on the Wild Side (FAB Press, 2006), I was given a copy of the screenplay adaptation of Childhood's End Abraham Polonsky wrote in the early 1970s, which Donald Cammell had hoped to direct. Although not widely known, and seldom if ever referred to in discussions of Polonsky's work after he ceased film directing, I'd love to know what Clarke thought of it.

Fort’s assertion that “We are property” is the unstated premise of “The Sentinel,” as it is for 2001. As it turns out, many years later, in one of those unexpected turns of which life consists, as part of the research for the book I co-authored with Rebecca Umland, Donald Cammell: A Life on the Wild Side (FAB Press, 2006), I was given a copy of the screenplay adaptation of Childhood's End Abraham Polonsky wrote in the early 1970s, which Donald Cammell had hoped to direct. Although not widely known, and seldom if ever referred to in discussions of Polonsky's work after he ceased film directing, I'd love to know what Clarke thought of it.

Some years ago Peter Nicholls observed in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (St. Martin’s Press, 1993), that the paradoxical legacy of Arthur C. Clarke may be that while he is associated with technological progress, he at the same time may also be

best remembered for the image of mankind being as children next to the ancient, inscrutable wisdom of alien races. There is something attractive, even moving, in what can be seen in Freudian terms as an unhappy mankind crying out for a lost father; certainly it is the closest thing SF has yet produced to an analogy for religion, and the longing for God. (230)

But a recent BBC news report published this week reported:

Sir Arthur was quoted as saying religion was “a necessary evil in the childhood of our particular species,” and he left written instructions that his funeral be completely secular.

I am not at all surprised by this revelation, among the last wishes of a supremely intelligent writer of great imaginative reach, a man whose remarkable life spanned almost the entirety of the twentieth century.

Wednesday, March 19, 2008

She Bop

BOP GIRL

BOP GIRL

aka Bop Girl Goes Calypso

1957, 79m 43s

Trivia question: What was the name of the film in which Judy Tyler (pictured, left) appeared prior to starring in Jailhouse Rock with Elvis?

Answer: Bop Girl Goes Calypso (the on-screen title; the one-sheet and lobby cards I've seen simply read Bop Girl), which was shown on Turner Classic Movies late last night. Most sources I’ve consulted indicate that Bop Girl Goes Calypso was released through United Artists in July 1957, meaning that Judy Tyler had already died (4 July 1957) by the time it and her subsequent film, Jailhouse Rock, were released in theaters. Two years ago I had a student enrolled in one of my classes who grew up near the small town in Wyoming where Judy Tyler was critically injured in an automobile crash; she avers there is a commemorative marker to this day marking the spot where the terrible event occurred. She also told me the name of the small town, but for the life of me I can’t remember it. The location of the accident is sometimes listed as Laramie, Wyoming, but that would seem to be the place where she was taken by ambulance to the city hospital, not the actual location of the automobile accident. However, it seems to me there's some confusion over this matter, as the aforementioned student told me that local lore has it that Tyler was instantly killed in the crash and pronounced DOA at the Laramie hospital. I cannot claim to be able to resolve this matter.

Fifty years on, the primary interest of Bop Girl is as a museum piece. I'm not entirely sure of the meaning of “bop” in the title, as it doesn’t refer to jazz music (as in the truncated form of the term, bebop). I believe “bop” in this case may be a slang term for “hit," as in a musical hit—a "hit single." The movie’s narrative formula is similar to that found in other films made for teenagers at the time—Don’t Knock the Rock (1956), for instance, is a good example—in which a romantic rivalry serves as a sort of corollary to the competing forms of popular music foregrounded in each film. (Career and romance go hand-in-hand, success in one complementing success in the other.) The nerdy protagonist of Bop Girl is Bob Hilton (Bobby Troup, pictured above, right), a graduate student in psychology. His thesis is tentatively titled, “Mass Hysteria and the Popular Singer,” and he is attempting to demonstrate empirically (by means of an applause meter, a clunky apparatus that appears throughout the film) that rock ‘n’ roll is on the verge of being displaced by calypso music. Improbably, his balding, equally nerdy academic mentor, Professor Winthrop (Lucien Littlefield, then nearing the end of a long acting career in the movies, dating back to the silent era), is a fan of rock ‘n’ roll. Upon hearing the conclusions Bob has drawn from his “scientific” research, he is distressed to learn that rock ‘n’ roll is yet just another passing fad. In contrast, Professor Winthrop’s good friend, Barney (prolific character actor George O'Hanlon, later the voice of TV’s George Jetson), the hot-tempered owner of a club, the Down Beat, catering to the rock ‘n’ roll crowd, dismisses Bob’s conclusions, averring rock ‘n’ roll is here to stay. But in order to save his friend’s economic future, however, Professor Winthrop convinces the Down Beat’s primary audience draw, the lovely singer, dancer, and bop girl Jo Thomas (Judy Tyler), to learn calypso in her spare time. Her calypso music adviser is none other than egghead Bob Hilton, with whom she becomes romantically involved, despite the fact that Bob is currently engaged to fellow brainy graduate student Marion Hendricks (Margo Woode). In the meantime, the recalcitrant club-owner Barney discovers the growing popularity of calypso music. He goes native, adopting the requisite clothing (including the straw hat) and renaming his establishment Club Trinidad. Just as Bob had predicted, the (former) rock ‘n’ roll fans go calypso crazy, and Jo Thomas becomes a calypso performer eagerly sought out by A&R talent scouts seeking to sign her to a recording contract. At the conclusion of the narrative, she and Bob have become a romantic couple, her career is on its way, while Marion is shown dancing with Professor Winthrop. [!]

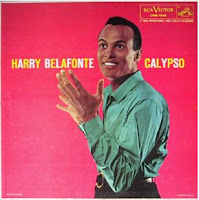

As directed by Howard W. Koch, who the next year would direct Boris Karloff in Frankenstein 1970 (1958), Bop Girl is neither better nor worse than other “topical” films of the period that in one way or another were reactions to the rise of rock ‘n’ roll. Clearly the film was attempting to ride the crest of the huge popularity of Harry Belafonte’s album Calypso (1956), the first vinyl LP (as opposed to single) to sell over one million copies (31 weeks at #1, 58 weeks in the top 10, 99 weeks on the music charts).  Yet unlike Don’t Knock the Rock, in which the postwar collapse of swing served as a means to historically validate the rise of rock ‘n’ roll as a popular form of music, Bop Girl simply manufactures any supposed competition between calypso and rock ‘n’ roll. Oddly, despite its titular reference to calypso, most of the songs are rock ‘n’ roll numbers, interspersed with a hybrid form of calypso music (such as “Calypso Boogie”), written or co-written by Les Baxter. The only calypso music as such in the film is performed by Lord Flea. Other performers, many of whom went on to have rather substantial careers, include saxophonist Nino Tempo (who opens the film with a fine jump tune), The Titans (doo wop), The Goofers (quirky R&B, quirky in a good way), and the Las Vegas lounge act, The Mary Kaye Trio. I'll confess my primary motive for seeing Bop Girl was to see Judy Tyler in a pre-Jailhouse Rock role, and in this regard I was not disappointed. In fact, she's prettier and sexier in Bop Girl than she is in Jailhouse Rock, in which performance was more restrained, more matronly. (The movie was all about Elvis, after all, not her.)

Yet unlike Don’t Knock the Rock, in which the postwar collapse of swing served as a means to historically validate the rise of rock ‘n’ roll as a popular form of music, Bop Girl simply manufactures any supposed competition between calypso and rock ‘n’ roll. Oddly, despite its titular reference to calypso, most of the songs are rock ‘n’ roll numbers, interspersed with a hybrid form of calypso music (such as “Calypso Boogie”), written or co-written by Les Baxter. The only calypso music as such in the film is performed by Lord Flea. Other performers, many of whom went on to have rather substantial careers, include saxophonist Nino Tempo (who opens the film with a fine jump tune), The Titans (doo wop), The Goofers (quirky R&B, quirky in a good way), and the Las Vegas lounge act, The Mary Kaye Trio. I'll confess my primary motive for seeing Bop Girl was to see Judy Tyler in a pre-Jailhouse Rock role, and in this regard I was not disappointed. In fact, she's prettier and sexier in Bop Girl than she is in Jailhouse Rock, in which performance was more restrained, more matronly. (The movie was all about Elvis, after all, not her.)

My original intention was to perform an analysis of Bop Girl Goes Calypso using the terms I’d employed in my earlier, January 16 blog entry on Nat King Cole (in the entry titled “The Pale Gaze”), but instead I’ll simply point readers to my earlier post as well as a very interesting analysis of the film that can be found here.