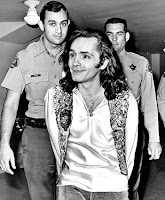

The question of Charles Manson and the “snuff film” has preoccupied my thoughts the past few days, prompted, of course, by the forensic investigation currently going on at the Barker Ranch (see my recent blog entries on the subject, below).

The question of Charles Manson and the “snuff film” has preoccupied my thoughts the past few days, prompted, of course, by the forensic investigation currently going on at the Barker Ranch (see my recent blog entries on the subject, below).

It occurs to me that the controversy surrounding the possible existence of the “snuff film” (never proven) is in fact no longer relevant—if the issue is simply one of transgression, the exhibition of content that is putatively considered “obscene”: this is merely a question of propriety, what ought to be shown and not shown. In a culture such as ours that is so preoccupied with the technology of war, we are able to see snuff film, in the sense of the filming of murder and the recording of death, just about every night on the national news, comprised as it is of video footage of missiles striking enemy strongholds, rockets raining down on “insurgents” hiding behind city walls or within buildings, the aftermath of car bombs with bodies littering the street, and numerous other atrocities.

The issue of televised snuff reveals that the so-called problem or controversy surrounding the snuff film exists because of photographic technology. In his essay on the art of the cinema, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image” (1945), André Bazin argued that photography had a privileged access to truth because it was the result of a mechanical, reproductive process over which human agency had no control. He thus regarded the cinema primarily as a vehicle of revelation, rather than transformation, of reality. “For the first time,” he wrote, “an image of the world is formed automatically, without the creative invention of man.” Bazin’s idea of an image being formed “automatically” is called the principle of automatism. Historically considered, Bazin privileges the form of mimesis known as aletheia (revelation), in contrast to adaequatio (correspondence). But in both of these modes of truth, the act of representation brings into appearance the physis (essence of life) of that which is imitated.

The history of photography reveals that automatism, the potential for revelation, became one of its primary attractions. A marketing campaign by Kodak once touted the importance of photography’s automatism—there was a camera nicknamed the “Kodak Automatic”—by its ability to capture “precious moments”—weddings, births, anniversaries, graduations, award ceremonies, family reunions and the like, all of those “once in a lifetime” events upon which so much of our modern memory is formed. By the same token, photography’s automatism has enabled some catastrophic historic moments to be captured on film: the explosion of the Hindenburg, for instance, on May 6, 1937, at the naval air station at Lakehurst, New Jersey (pictured), or the stark truth of the Nazi death camps. There’s the famous, Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph taken by photojournalist Eddie Adams in Saigon in 1968, capturing the execution of a Viet Cong prisoner. Most Americans, I imagine, have the images of the collapsing World Trade Center Towers indelibly etched in their memory—I certainly do—an event made possible by the automatism of photography and the ubiquity of the inexpensive video camera.

Thus the principle of automatism allows photographic technology to capture atrocity as well. Considered strictly as a form of technology, photography illustrates what Edward Tenner calls the “revenge effect” of all technology: a process designed for one purpose turns out not only to subvert that purpose but to achieve its opposite.

The principle of photography’s automatism enables “Reality TV” as a form of representation but, paradoxically, creates a problem it must simultaneously overcome: there is the real, but there is also the too real. Reality TV must disclose (reveal) but also occlude (shut off, hide) at the same time. For instance, the subject of a "Reality TV" may use the toilet, but the camera doesn't intrude on the subject's privacy. In order to illustrate the nature of this dilemma, an anecdote is in order. Some years ago, I read a letter in Ann Landers’ column from a woman who, while snooping through her teenage daughter’s purse, had discovered birth control pills. She was writing to Ann Landers for advice on how to best handle her dilemma: she wanted to talk to her daughter about the daughter’s presumed promiscuity, but to do so she would have to admit to her daughter that she had been snooping through her daughter’s purse. (In her reply, Ann Landers suggested the problem originated with the mother’s lack of trust in her daughter, which is precisely why the daughter kept the pills hidden away.) The moral of the story is that in her remorseless, voyeuristic search for what was real, the mother became an eye-witness to something she didn’t wish to see—to know (knowledge as seeing). The mother should have been more familiar with Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex.

The makers of “Reality TV” programs face the same daunting problem that the nosy mother did while rummaging through her daughter’s purse: how to reveal the truth, but not to go too far, not to pass a certain proscribed limit. The problem isn't so much what you can show as what you can't show. If you go too far, for example, you find yourself confronting the outrage caused by the exposure of Janet Jackson’s breast during the Super Bowl XXXVIII half-time show (2004)—the problem of the intrusion of the real, which gets you into trouble. On the other hand, if you don’t show (reveal) enough, you can’t claim to be presenting “reality.”

The Lacanian critic Slavoj Zizek conveniently addresses this problem by using as an illustration a love scene in a Hollywood film:

Let us take an old-fashioned, nostalgic melodrama like Out of Africa and let us assume that the film is precisely the one shown in cinemas, except for an additional ten minutes. When Robert Redford and Meryl Streep have their first love encounter, the scene—in this slightly longer version of the film—is not interrupted, the camera “shows it all,” details of their aroused sexual organs, penetration, orgasm, etc. Then, after the act, the story goes on as usual, we return to the film we all know. The problem is that such a movie is structurally impossible. Even if it were to be shot, it simply “would not function”; the additional ten minutes would derail us, for the rest of the movie we would be unable to regain our balance and follow the narration with the usual disavowed belief in the diegetic reality. The sexual act would function as an intrusion of the real undermining the consistency of this diegetic reality. (Looking Awry, MIT Press, 1992, p. 111)

Stated another way, movies are commercially successful only to the extent that they are magical, that they enchant the viewer. They cease to enchant or enthrall when brute fact intrudes on the theatrical frame: dreary fact is rather like a spoilsport who destroys the illusory world of the game. To “show it all” is to go way too far, to dispel the illusion, that is, to allow the real to intrude—just ask Janet Jackson. The revenge effect of photography’s automatism is the vulnerability of the photographic medium to the too real. For his example, Zizek uses sex; in my subsequent blog, I will use death—flip side of the same token. While its existence has never been proven, the theoretical existence of the "snuff film" was made thinkable in the first place because of the potential for photographic technology to so easily—automatically—record the too real.

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

Snuff, Reality TV, and the Issue of the "Too Real": Part 1

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

Death Valley Days: 1.1

The current dig at the Barker Ranch is promising to become the equivalent of Geraldo Rivera's opening of Al Capone's vault. Here are excerpts from this afternoon’s Los Angeles Times website report, filed by Louis Sahagun at 4:36 p.m. PDT (updates may supplant this initial report):

The current dig at the Barker Ranch is promising to become the equivalent of Geraldo Rivera's opening of Al Capone's vault. Here are excerpts from this afternoon’s Los Angeles Times website report, filed by Louis Sahagun at 4:36 p.m. PDT (updates may supplant this initial report):

A day’s work in 100-degree heat at a remote ranch once used as a hangout for the notorious Charles Manson family yielded only a .38-caliber shell casing today. But a posse of Inyo County sheriff’s investigators was expected to continue the dig in Death Valley National Park.

[...]

Of particular interest today were two sites where cadaver dogs and analyses of soil samples produced mixed but somewhat encouraging results that could possibly support lingering rumors that bodies may be buried at Barker Ranch. The collection of sheds and a rock-and-plaster ranch house are five miles up a rugged black rock canyon at the park’s southwestern boundary.

Inyo County Sheriff Bill Lutze has said a total of five sites may be excavated over the next few days amid temperatures forecast to hover near 110 degrees. Sheriff’s authorities were expected to provide reporters with a progress report later today.

To reiterate: we shall see. Aside from the allegation, without source, by a former Manson "Family" member that there are bodies buried at the Barker Ranch, there may be other motivations for the dig that are, in fact, unrelated to the Mansion "Family."

Death Valley Days: One

An update on yesterday afternoon's blog about the archaeological/forensic dig going on at the Barker Ranch, the remote set of buildings in the Panamint Mountains at the southwestern edge of Death Valley used by Charles Manson and his “Family” as a refuge in 1968-69: this afternoon the Los Angeles Times provided an update on the excavation, but no new details were added to the report.

An update on yesterday afternoon's blog about the archaeological/forensic dig going on at the Barker Ranch, the remote set of buildings in the Panamint Mountains at the southwestern edge of Death Valley used by Charles Manson and his “Family” as a refuge in 1968-69: this afternoon the Los Angeles Times provided an update on the excavation, but no new details were added to the report.

However, after having re-read yesterday’s blog, it occurred to me that I might have given too much emphasis to the issue of the “snuff” film rather than the issue of whether there might be bodies buried near the Barker Ranch in that remote area of Death Valley. As I pointed out, the use of “snuff” to refer to films (or videotape) purportedly containing scenes of actual murder was originated by Ed Sanders in his 1971 book on Manson, The Family (most recently reissued in 2002). But it occurred to me that there are actually two, unrelated, issues here: whether there were, in fact, any “snuff films” ever made, by Manson and his “Family” or by others, on 8mm or other storage media; and whether there might be any bodies to be found buried in the environs of the Barker Ranch.

Having reflected on the issue, I'm now wondering why law enforcement authorities believe there might be bodies buried near the Barker Ranch in the first place. My interest rekindled by the archaeological/forensic research mission presently going on, this morning I was motivated to re-read Ed Sanders' The Family, the first edition hardcover I bought in the early 1970s (the edition published prior to a lawsuit that required its author to remove any references to "The Process"). He makes no reference to murders or burials that might have taken place at the Barker Ranch, although he does refer to murders in the state that occurred when Manson Family members were placed in the area. One brief sentence, however, in today's report explains the reason for the recent investigation:

A member of the Manson family later suggested that there were bodies buried at Barker Ranch.

Apparently this information surfaced many years after Sanders published his book. I should note that a preliminary dig occurred at the ranch in February of this year, so perhaps the information surfaced only recently.

To reiterate the conclusion I made at the end of yesterday's blog: we shall see.

Silly Love Songs

I am sure it will come as no surprise to anyone for me to say that the vast majority of popular songs are love songs. And although this fact may surprise no one at all--indeed, may be a painfully banal observation--no one, to my knowledge, discusses it. Indeed, it is one of those "obvious" facts of our daily lives that is rarely, if ever, discussed. I'm sure we've heard it said a thousand times, "it is a fundamental desire for human beings to love and to want to be loved," but the insight is no more startling or profound or meaningful, as a simple declarative sentence, than "the sky is blue." For scholars who approach popular music from a sociologist's perspective, such as Simon Frith, the fact that the bulk of popular songs are love songs "is more than an interesting statistic; it is a centrally important aspect of how pop music is used" ("Towards an Aesthetic of Popular Music," in Music and Society, Cambridge University Press, 1987, p. 141). For Simon Frith, it is one of the social functions of popular music "to give us a way of managing the relationship between our public and private emotional lives." Why are love songs so important to us? Frith asks.

I am sure it will come as no surprise to anyone for me to say that the vast majority of popular songs are love songs. And although this fact may surprise no one at all--indeed, may be a painfully banal observation--no one, to my knowledge, discusses it. Indeed, it is one of those "obvious" facts of our daily lives that is rarely, if ever, discussed. I'm sure we've heard it said a thousand times, "it is a fundamental desire for human beings to love and to want to be loved," but the insight is no more startling or profound or meaningful, as a simple declarative sentence, than "the sky is blue." For scholars who approach popular music from a sociologist's perspective, such as Simon Frith, the fact that the bulk of popular songs are love songs "is more than an interesting statistic; it is a centrally important aspect of how pop music is used" ("Towards an Aesthetic of Popular Music," in Music and Society, Cambridge University Press, 1987, p. 141). For Simon Frith, it is one of the social functions of popular music "to give us a way of managing the relationship between our public and private emotional lives." Why are love songs so important to us? Frith asks.

Because people need them to give shape and voice to emotions that otherwise cannot be expressed without embarrassment or incoherence. Love songs are a way of giving emotional intensity to the sorts of intimate things we say to each other (and to ourselves) in words that are, in themselves, quite flat. It is a peculiarity of everyday language that our most fraught and revealing declarations of feeling have to use phrases--'I love/hate you', 'Help me!', 'I'm angry/scared'--which are boring and banal; and so our culture has a supply of a million pop songs, which say these things for us in numerous interesting and involving ways. (141)

There's another way to explain why our culture has a million songs about love, though, and it has been expressed by a prominent musician and songwriter, jazz sage Mose Allison. During an interview with Joel Dorn (cited in the liner notes to Allison Wonderland: The Mose Allison Anthology, Atlantic, 1994) Allison said this, which I hope we'll ponder the next time we hear one of those "silly" love songs on the radio:

A prominent white educator was studying the culture of the Hopi, a desert-dwelling Native American tribe of the Southwest. He found it strange that almost all Hopi music was about water and asked one of the musicians why. He explained that so much of their music was about water because that was what they had the least of. And then he told the white man, "Most of your music is about love."

Monday, May 19, 2008

Death Valley Days

According to a report published this afternoon on the Los Angeles Times website, early tomorrow morning (Tuesday), Inyo County Sheriff’s investigators, accompanied by forensic scientists, will begin lugging portable ground-penetrating radar, magnetometers, shovels, and other excavating tools up to the Barker Ranch at the edge of Death Valley on a mission to confirm or deny speculation that there may be graves at the ranch, used in 1969 as a secluded hideout by Charles Manson and his so-called “Family.” The excavation at the Barker Ranch, located at the southern end of Death Valley National Park—in terrain so formidable that it can only be reached by 4-wheel drive vehicles—is expected to continue through Thursday.

According to a report published this afternoon on the Los Angeles Times website, early tomorrow morning (Tuesday), Inyo County Sheriff’s investigators, accompanied by forensic scientists, will begin lugging portable ground-penetrating radar, magnetometers, shovels, and other excavating tools up to the Barker Ranch at the edge of Death Valley on a mission to confirm or deny speculation that there may be graves at the ranch, used in 1969 as a secluded hideout by Charles Manson and his so-called “Family.” The excavation at the Barker Ranch, located at the southern end of Death Valley National Park—in terrain so formidable that it can only be reached by 4-wheel drive vehicles—is expected to continue through Thursday.

I look forward to the findings of this intriguing archaeological/forensic research mission, as it has been rumored for almost forty years that the Manson Family committed murders that were recorded on film (or video, depending on the specific version of the rumor). I invite readers to read David Kerekes and David Slater’s book, Killing For Culture (Creation Books, 1994) for further information on the putative Barker Ranch murders. Kerekes and Slater aver that the idea of the Manson family making “snuff” films dates back to Ed Sanders’ book on Charles Manson, The Family (first published by E.P. Dutton, 1971). It was Ed Sanders, in this book, who coined the term “snuff” to describe the content of these elusive films purportedly containing scenes of actual murder. Kerekes and Slater write:

These “whispers” [of snuff films] date back to Ed Sanders’ book, The Family. Here, Sanders states that Family members stole an NBC-TV wagon loaded with film equipment sometime during the Summer of 1969. The truck was subsequently dumped and most of the film given away, but Manson took one of the NBC cameras with him to Death Valley in September [1969]. The Family were also in possession of three Super-8 cameras. It is alleged that they shot porn-movies and, determines Sanders, “the Barker Ranch chop-stab dance, where they [the Family] danced in a circle, then pretended to go into frenzies—attacking trees, rocks and one another with knives.” He adds, “God knows what else they shot with their stolen NBC camera”.... Speaking with an anonymous one-time member of the Family, Sanders learns of a “short movie depicting a female victim dead on a beach” (Killing For Culture, p. 223).

According to the Los Angeles Times report, locals in the area predict the investigators will turn up nothing but ancient Indian graves. Others, however, say the situation is more problematic in that some California state park rangers claim that if indeed human remains are discovered at the Barker Ranch, they may be connected to an unrelated Death Valley mystery from 1996, the mysterious disappearance of four German tourists.

We shall see.

Something's Up My Sleeve

Yesterday’s blog on the art of rock art prompted me to think about the art of the album cover—the vinyl LP album cover specifically. I say “cover,” but is that the proper nomenclature? Why not “jacket,” or “sleeve”? With the advent of the compact disc jewel case, the material aspect of a vinyl LP’s “jacket,” “cover,” “sleeve,” or “wrapper” is no longer applicable, although a recent development in the music industry has been to reissue albums on compact disc in CD-sized sleeves that duplicate the “original art work" of the LP. The restoration of the original album art reflects a desire, I suppose, for presence, an attempt, writes John Corbett, “to stitch the cut that separates seeing from hearing in the contemporary listening scenario” (Extended Play: Sounding Off from John Cage to Dr. Funkenstein, Duke University Press, 1994, p. 39). For Corbett, the album cover is an "attempt to reconstitute the image of the disembodied voice" (p. 39) to recorded sound.

Having thought about the issue the past twenty-four hours, and having spent some time browsing through my LP collection, I here present my Top 11 favorite album covers—and why eleven? Because I can do as I please; I don't have to limit myself to ten. Why are they my favorites? Because they enchant me without my knowing exactly why: as Roland Barthes observed, "such ignorance is the very nature of fascination" (Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, Hill and Wang, 1977, p. 3). Do my selections belie my age? Probably, but I would hope that others find my choices as inherently fascinating as I do.

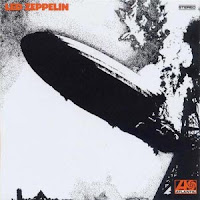

1. Led Zeppelin—Led Zeppelin (Atlantic, 1969); designer, George Hardie.

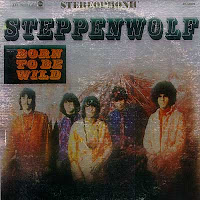

2. Steppenwolf—Steppenwolf (Dunhill, 1968); designer: Gary Burden; photographer: Tom Gundelfinger.

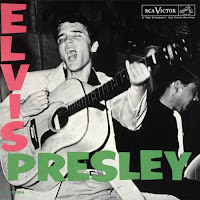

3. Elvis Presley—Elvis Presley (RCA, 1956); designer: Colonel Tom Parker; photographer: Popsie [William S. Randolph].

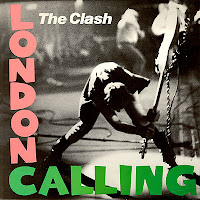

4. London Calling—The Clash (Epic, 1979); designer: Ray Lowry; photographer: Pennie Smith.

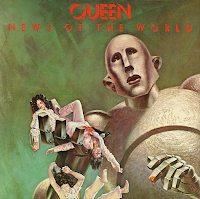

5. News of the World—Queen (Elektra, 1977); designer: Roger; painting: Frank Kelly Freas (1953).

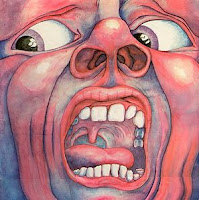

6. In the Court of the Crimson King—King Crimson (Atlantic, 1969); painting: Barry Godber.

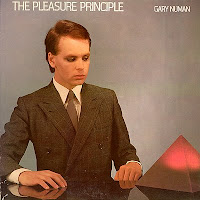

7. The Pleasure Principle—Gary Numan (Atco, 1979); designer: Malti Kidia; photographer: Geoff Howes.

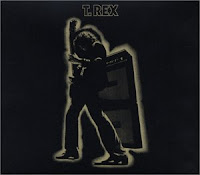

8. Electric Warrior—T. Rex (Warner Brothers, 1971); designer: Hipgnosis.

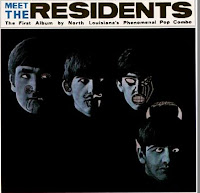

9. Meet the Residents—The Residents (Ralph, 1974); designer: Porno/Graphics; photographer: Robert Freeman.

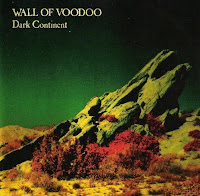

10. Dark Continent—Wall of Voodoo (I.R.S., 1981); designer: Philip Culp; photographer: Scott Lindgren.

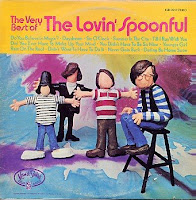

11. The Very Best of the Lovin’ Spooful—The Lovin’ Spoonful (Kama Sutra, 1970); sculpture: Ollie Alpert.