Wednesday, April 21, 2010

Weed Day

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Beyond Good and Elvis

The connection of fanaticism and fetishism is conveniently revealed in a video currently available on youtube.com that I consider required viewing for anyone interested in the phenomenon, consisting of an excerpt from Thomas Corboy’s short documentary Rock ‘n’ Roll Disciples (1986). A range of Elvis fans are interviewed, including Artie Mentz (an Elvis impersonator), Jenny and Judy Carroll (identical twins who believe they may be Elvis’s illegitimate offspring), and Frankie “Buttons” Horrocks, who has devoted her life to the witnessing and the celebration of Elvis. There’s a moment in the video during which Horrocks observes that no true female Elvis fan denies her deep desire to have had sex with Elvis. As she speaks, she is shown posing with the Elvis statue now standing in Memphis, her hand firmly gripping its crotch. Greil Marcus observes the image “is reminiscent of nothing so much as the statues of Catholic saints that in present-day Europe good Christian women straddle in pagan ecstasy, telling anyone who asks that their mothers said it was a good way to ensure fertility” (Dead Elvis 119)—that is, the image reveals the nature of the relationship between the fan and the fetish object.

Monday, April 19, 2010

Cowry Shell

A Few Explicit Fetishes:

Joe Bennett and the Sparkletones – Black Slacks

Tony Bennett – Blue Velvet

Big Bopper – Chantilly Lace

Dee Clark – Hey Little Girl (In the High School Sweater)

David Allan Coe – Angels in Red

Derek and the Dominos – Bell Bottom Blues

Bob Dylan – Boots of Spanish Leather

The Eagles – Those Shoes

Brian Hyland – Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini

The Hollies – Long Cool Woman in a Black Dress

Kenny Owen – High School Sweater

Carl Perkins – Blue Suede Shoes

Mitch Ryder & The Detroit Wheels – Devil With A Blue Dress On

Rod Stewart – You Wear It Well

Royal Teens – Short Shorts

Conway Twitty – Tight Fittin’ Jeans

Sunday, April 18, 2010

Steal This Blog

In art and literature, self-referentiality is sometimes referred to as self-reflexivity, occurring when the artist or writer refers to the work in the context of the work itself – as does “The Song That Never Ends.” There are many children's songs that privilege recursivity and self-reflexivity, but there are also many great examples of self-reflexive pop songs as well. Perhaps the most well known of these songs is Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain,” in which she sings, “You probably think this song is about you.” Another is Steely Dan’s “Deacon Blues,” when Donald Fagen sings, “I cried when I wrote this song/Sue me if I play too long.” My favorite illustration, though, is probably Neil Young’s “Borrowed Tune,” from Tonight’s the Night:

In the 60s self-reflexivity was often employed as a form of culture jamming, the act of defamiliarizing signs and slogans in order to disrupt habitual, or largely uncritical, patterns of perception and consumption. A famous example of culture jamming from the era is Abbie Hoffman’s Steal This Book, published in 1971 (pictured), which, ironically, sold extremely well, primarily because much of the book offered advice on how to survive with little or no money. There have been entire albums created based on the principle of culture jamming; one of the most singular is The Residents’ The Third Reich 'N' Roll (1976), consisting of defamiliarized versions of Top 40 radio hits of the 1960s. Not all self-reflexive pop songs have such a radical agenda, of course, but all have the effect of disrupting the usual, that is, habitual, patterns of communication.

A Self-Reflexive Play List:

Edward Bear – Last Song

Elton John – Your Song

David Allan Coe – You Never Even Called Me By My Name

Arlo Guthrie – Alice’s Restaurant

Pink Floyd – Mother

Public Image Ltd. – This Is Not A Love Song

Carly Simon – You’re So Vain

Steely Dan – Deacon Blues

James Taylor – Fire and Rain

The Who – Gettin’ In Tune

“Weird Al” Yankovic – Smells Like Nirvana

Neil Young – Borrowed Tune

Saturday, April 17, 2010

Pop Guns

Blame It On Cain:

Aerosmith – Janie’s Got A Gun

Black Velvet Flag – I Shot JFK

Johnny Cash – Folsom Prison Blues

Steve Earle – The Devil’s Right Hand

Bobby Fuller Four – I Fought The Law

Pat Hare – I’m Gonna Murder My Baby

The Jimi Hendrix Experience – Hey Joe

The Kingston Trio – Tom Dooley

The Louvin Brothers – Knoxville Girl

Nas – I Gave You Power

Gene Pitney – The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

Kenny Rogers and The First Edition – Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love To Town

The Rolling Stones – Midnight Rambler

Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska

The Wailers – I Shot the Sheriff

Hank Williams, Jr. – I’ve Got Rights

Neil Young – Down by the River

Friday, April 16, 2010

Wind and Wuthering

In pre-literate, oral civilizations, people experienced their thoughts not as coming from within themselves, but from outside, as Spirit. A thought seemed to come from the gods, or a tree, or a bird, that is, from the outside. Literacy, however, transformed the nature of the subject. To the literate mind, the experience of Self is the experience of interiority: Spirit resides within, as Psyche. In literate experience, therefore, thought originates from inside. Of course, as a consequence of literacy, there was a huge reduction in our relationship with Nature, but for the Romantics, we also won a kind of liberty, the virtue of self-reflection that came with being a discrete self. In order to renew their relationship with Nature, Coleridge and the other Romantics sought to recreate the experience of orality, conveyed by the image of the Aeolian harp, a common household instrument before and during the Romantic Era. (By way of analogy, think of the wind chime.) Just as the harp depends upon the wind for its sound, so, too, does the (passive) poet depend upon the wind for poetic inspiration, as expressed, for instance, in Shelley's “Ode to the West Wind.” Having become strongly associated with the activity of the creative mind, Ralph Waldo Emerson also used the Aeolian harp as a metaphor for the mind of the (Romantic) poet.

In pre-literate, oral civilizations, people experienced their thoughts not as coming from within themselves, but from outside, as Spirit. A thought seemed to come from the gods, or a tree, or a bird, that is, from the outside. Literacy, however, transformed the nature of the subject. To the literate mind, the experience of Self is the experience of interiority: Spirit resides within, as Psyche. In literate experience, therefore, thought originates from inside. Of course, as a consequence of literacy, there was a huge reduction in our relationship with Nature, but for the Romantics, we also won a kind of liberty, the virtue of self-reflection that came with being a discrete self. In order to renew their relationship with Nature, Coleridge and the other Romantics sought to recreate the experience of orality, conveyed by the image of the Aeolian harp, a common household instrument before and during the Romantic Era. (By way of analogy, think of the wind chime.) Just as the harp depends upon the wind for its sound, so, too, does the (passive) poet depend upon the wind for poetic inspiration, as expressed, for instance, in Shelley's “Ode to the West Wind.” Having become strongly associated with the activity of the creative mind, Ralph Waldo Emerson also used the Aeolian harp as a metaphor for the mind of the (Romantic) poet.

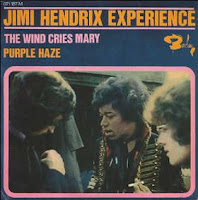

Through the principle of contiguity (metonymy), a thing can be referred to not by its name but by the name of something associated with it. I can say, “Let’s stand in the shade,” but I may be actually saying, “Let’s stand under the leafy branches of that tree over there.” Wind and sand have come to be associated in such a manner, represented by the image of the sand dune, sculpted by the wind. Because wind and sand are interchangeable, and sand is a conventional image for Time (think: hourglass), a phrase such as “dust in the wind” actually refers to power of Time to erase everything one knows, including the trace of one’s own existence. Wind is a constant reminder of one’s mortality. The figurative phrase, “wind of change,” thus names the ineluctable activity of Time. Hence when Jimi Hendrix sings of the wind in his meditation on fame and mortality, “The Wind Cries Mary,” he’s actually reflecting on his own historical significance:

Substitute “my name” for “the names it has blown in the past,” and the point seems clear enough. For a recent song that attempts to reestablish the link between wind and Spirit, listen to “Colors of the Wind,” from the Pocahontas soundtrack.

The Association – Windy

The Byrds – Hickory Wind

Bob Dylan – Blowin’ in the Wind

Patsy Cline – Wayward Wind

Julee Cruise – Slow Hot Wind

Donovan – Catch the Wind

Elton John – Candle in the Wind

England Dan & John Ford Coley – I’d Really Love to See You Tonight

Jethro Tull – Cold Wind to Valhalla

Jimi Hendrix – The Wind Cries Mary

Kansas – Dust in the Wind

Judy Kuhn – Colors of the Wind (Pocahontas Original Soundtrack)

Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band – Against the Wind

Frank Sinatra – Summer Wind

Traffic – Walking in the Wind