In Tikaboo Valley, Nevada, the only significant landmark along a long, lonely stretch of Nevada’s Highway 375—officially named the “Extraterrestrial Highway”—is the so-called black mailbox. (The actual object is painted white, however.) The white mailbox is referred to by the name of the object it replaced, a black one, and is located near the infamous Area 51, largely accounting for the notoriety of such a banal, quotidian object such as a receptacle for the daily mail. The nearby proximity to Area 51 has allowed for the black mailbox to gain notoriety through the operation of metonymy, or reference by association.

In Tikaboo Valley, Nevada, the only significant landmark along a long, lonely stretch of Nevada’s Highway 375—officially named the “Extraterrestrial Highway”—is the so-called black mailbox. (The actual object is painted white, however.) The white mailbox is referred to by the name of the object it replaced, a black one, and is located near the infamous Area 51, largely accounting for the notoriety of such a banal, quotidian object such as a receptacle for the daily mail. The nearby proximity to Area 51 has allowed for the black mailbox to gain notoriety through the operation of metonymy, or reference by association.

According to a recent article in the Los Angeles Times, the black (white) mailbox on Highway 375 has become a holy shrine of sorts, a gathering place, for UFO pilgrims, who travel for miles upons miles just to get a look at it, and presumably, to touch it. According to the L. A. Times report,

Over the years, hundreds of people have converged here in south-central Nevada to photograph the box—the size of a small television, held up by a chipped metal pole. They camp next to it. They try to break into it. They debate its significance, or simply huddle by it for hours, staring into the night.

Some think the mailbox is linked to nearby Area 51, a military installation and purported hotbed of extraterrestrial activity. At the very least, they consider the box a prime magnet for flying saucers.

A few visitors have claimed they saw celestial oddities. But most enjoy even uneventful nights at the mailbox, about midway between the towns of Alamo and Rachel. Alien hunters here are surrounded by like-minded—meaning open-minded—company. In a place where the welcome sign to Rachel reads, Humans: 98, Aliens: ?, few roll their eyes at tales of spaceships, military conspiracies and extraterrestrials that abduct and impregnate tourists.

The modern UFO era began in June 1947 with pilot Kenneth Arnold’s report that he saw flying aircraft moving at a high speed near Mount Rainier, Washington, that were shaped like saucers or discs. Given his description of the ships, the media, always inevitably in search of the sound bite, dubbed these craft “flying saucers.”

Since the beginning of the modern UFO era is virtually simultaneous with the beginning of the rock era, it therefore should be no surprise that rock ‘n’ rollers have been fascinated by UFOs, and now and then have written songs about them. Jimi Hendrix allegedly was fascinated by The Urantia Book, a text known to many UFO enthusiasts, one that mixed stories about Jesus with tales of alien visitations on Earth (Urantia being an occult name for the Earth). And according to his biographer Albert Goldman, Elvis also owned a copy of The Urantia Book. Rock groups naming themselves The Foo Fighters and UFO also acknowledge the cultural fascination with UFOs. Here are a few examples of songs from the rock era (including one album) alluding to aliens, flying saucers, and spaceships, and science fiction themes in general. At least two of them ("The Flying Saucer," "The Purple People Eater"--who plays "rock and roll music through the horn in his head"--, both from the late 1950s) are "novelty" songs, but perhaps all the following songs might all be considered as such.

Billy Bragg & Wilco - My Flying Saucer

Bill Buchanan & Dickie Goodman - The Flying Saucer

Ry Cooder – UFO Has Landed in the Ghetto

Béla Fleck & The Flecktones

- Flying Saucer Dudes

Hüsker Dü – Books About UFOs

Klaatu - Calling Occupants Of Interplanetary Craft

Kyuss – Spaceship Landing

Nektar – Remember the Future (LP, 1973)

Graham Parker and the Rumour – Waiting for the UFOs

Parliament – Unfunky UFO

Styx – Come Sail Away

Sheb Wooley – The Purple People Eater

Yes – Arriving UFO

Neil Young – After the Gold Rush

Sunday, August 24, 2008

Waiting For The UFOs

Saturday, August 23, 2008

The Persistence of Sound

Reverb is echo (the repetition of sound) produced by electronic means (such as that produced by the Fender ’65 Twin Reverb Amp, pictured). Echo is to exteriority as reverberation is to interiority (the space of psychedelia). Wikipedia: “If so many reflections arrive at a listener that he is unable to distinguish between them, the proper term is reverberation [rather than echo].” Reverberation is

Reverb is echo (the repetition of sound) produced by electronic means (such as that produced by the Fender ’65 Twin Reverb Amp, pictured). Echo is to exteriority as reverberation is to interiority (the space of psychedelia). Wikipedia: “If so many reflections arrive at a listener that he is unable to distinguish between them, the proper term is reverberation [rather than echo].” Reverberation is

the persistence of sound in a particular space after the original sound is removed. When sound is produced in a space, a large number of echoes build up and then slowly decay as the sound is absorbed by the walls and air, creating reverberation, or reverb. This is most noticeable when the sound source stops but the reflections continue, decreasing in amplitude, until they can no longer be heard. Large chambers, especially such as cathedrals, gymnasiums, indoor swimming pools, large caves, etc., are examples of spaces where the reverberation time is long and can clearly be heard. Different types of music tend to sound best with reverberation times appropriate to their characteristics.

As Michael Jarrett observes: “Reverb sonically implies the size and shape of imaginary places that hold music” (72). If so, then echo implies the immensity of a large cave or cathedral, while reverberation collapses this immensity into the claustrophobic space inhabited by the cenobitic monk (the cell).

A Few Examples Of Reverb (Space Is The Place):

Dick Dale & His Del-Tones - Pipeline

Bo Diddley – Bo Diddley

Bo Diddley – Mona

Ennio Morricone – The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The O’Jays, For the Love of Money

Quicksilver Messenger Service – Mona

Link Wray – Rumble

The Essential Collection of Psychedelia And Reverb (My Mind's Such A Sweet Thing):

Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era 1965-1968

Tuesday, July 22, 2008

The Mellotron

The Mellotron, a keyboard instrument that was featured in early psychedelic music and later became an essential fixture of “Progressive” bands, was made possible by one of the spoils of World War II—electromagnetic tape. As Michael Jarrett notes in Sound Tracks (1998), "When U.S. troops invaded Radio Luxembourg, they "liberated" a tape machine and shipped it to the Ampex Corporation; further development was financed by Bing Crosby" (214). Technically considered, the Mellotron is a polyphonic, sample-playback keyboard system, the basis of which is a large bank of pre-loaded electromagnetic audio tapes, each of which consists of a pre-recorded sound. Each of the several magnetic tapes has roughly eight seconds of playing time: early user manuals strongly recommended that no key should be held for more than ten seconds. Playback heads underneath each of the keys allowed for the playing of the pre-recorded sounds, hence the reason it is considered a "sample-playback" system. Early Mellotron models, the MK-I and the MK-II, contained two keyboards set side-by-side: the right keyboard consisted of various selectable "instrumental" sounds (e.g., strings, flutes, various brass instruments), while the left keyboard consisted of rhythm tracks. The first Mellotrons--intended for the home, not for the arduous rock concert circuit--were made in Birmingham, England (although the prototype was initially developed in the United States), the reason why the earliest uses of the instrument were by British bands. Musician Mike Pinder (pictured above in the foreground, with the Moody Blues, playing a Mellotron MK-II) worked for Streetly Electronics, the company that manufactured the Mellotron, for about a year and half before joining the Moody Blues in 1967; he and the band are largely responsible for popularizing the Mellotron in popular music. Like the Moog synthesizer, also an electronic instrument, the Mellotron underwent development and refinement. The years of manufacture of the various models of the Mellotron are as follows:

The Mellotron, a keyboard instrument that was featured in early psychedelic music and later became an essential fixture of “Progressive” bands, was made possible by one of the spoils of World War II—electromagnetic tape. As Michael Jarrett notes in Sound Tracks (1998), "When U.S. troops invaded Radio Luxembourg, they "liberated" a tape machine and shipped it to the Ampex Corporation; further development was financed by Bing Crosby" (214). Technically considered, the Mellotron is a polyphonic, sample-playback keyboard system, the basis of which is a large bank of pre-loaded electromagnetic audio tapes, each of which consists of a pre-recorded sound. Each of the several magnetic tapes has roughly eight seconds of playing time: early user manuals strongly recommended that no key should be held for more than ten seconds. Playback heads underneath each of the keys allowed for the playing of the pre-recorded sounds, hence the reason it is considered a "sample-playback" system. Early Mellotron models, the MK-I and the MK-II, contained two keyboards set side-by-side: the right keyboard consisted of various selectable "instrumental" sounds (e.g., strings, flutes, various brass instruments), while the left keyboard consisted of rhythm tracks. The first Mellotrons--intended for the home, not for the arduous rock concert circuit--were made in Birmingham, England (although the prototype was initially developed in the United States), the reason why the earliest uses of the instrument were by British bands. Musician Mike Pinder (pictured above in the foreground, with the Moody Blues, playing a Mellotron MK-II) worked for Streetly Electronics, the company that manufactured the Mellotron, for about a year and half before joining the Moody Blues in 1967; he and the band are largely responsible for popularizing the Mellotron in popular music. Like the Moog synthesizer, also an electronic instrument, the Mellotron underwent development and refinement. The years of manufacture of the various models of the Mellotron are as follows:

Mellotron Mark-I (1962-63)

Mellotron Mark-II (1964-67)

M-300 (1968-70)

M-400 (1970-86)

The M-400 model, first sold in 1970, become part of the signature sound of the so-called “Progressive” bands of the 1970s. This model included tape banks that could be removed with relative ease and loaded with banks containing different sounds, including percussion loops, sound effects, and other noises. Hence, like pop music itself, the Mellotron is a consequence of electromagnetic tape.

Ten representative rock songs featuring the Mellotron, 1967-1973:

1. The Beatles - “Strawberry Fields Forever” Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967)

2. The Moody Blues - “Nights in White Satin” Days of Future Passed (1967)

3. The Rolling Stones - “2000 Light Years From Home” Their Satanic Majesties Request (1967)

4. The Zombies - “Brief Candles” Odessey & Oracle (1968)

5. Cream - “Badge” Goodbye (1969)

6. David Bowie - “Space Oddity” Space Oddity (1969)

7. King Crimson - “Epitaph” In the Court of the Crimson King (1969)

8. Genesis - “Watcher of the Skies” Foxtrot (1972)

9. Lynyrd Skynyrd - “Tuesday’s Gone” pronounced 'lĕh-'nérd 'skin-'nérd (1973)

10. John Lennon - “Mind Games” Mind Games (1973)

For those interested, a short demonstration from the mid-60s of the Mellotron MK-II, can be found here, while an interesting history of the Mellotron, by Mike Pinder of the Moody Blues, can be found here.

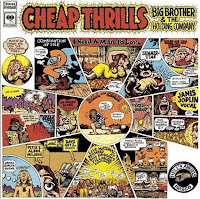

Cheap Thrills and the Wonderful Undead

Previously, in my blog entries of May 16, May 31, and July 1 I have discussed my experiment of trying to listen to all the rock and R&B albums released in the calendar year 1968 in the order in which they were released. I'll refer readers to my earlier blog entries for the explanation for such an unusual project (and all the pitfalls inherent in such an ongoing activity). Since I've already assembled it, I've gone ahead and posted August’s listening schedule. As I’ve stated many times before, I cannot claim my list is infallible, but I continue to work on it and to try and improve it. What I've discovered is that there were many albums released during the months of July and August 1968--more so in terms of numbers of releases in a single month than in any previous month--so as you can see, August’s list is rather long (assuming the information I've come across is accurate). Here's the dozen albums I have put together for August 1968:

Previously, in my blog entries of May 16, May 31, and July 1 I have discussed my experiment of trying to listen to all the rock and R&B albums released in the calendar year 1968 in the order in which they were released. I'll refer readers to my earlier blog entries for the explanation for such an unusual project (and all the pitfalls inherent in such an ongoing activity). Since I've already assembled it, I've gone ahead and posted August’s listening schedule. As I’ve stated many times before, I cannot claim my list is infallible, but I continue to work on it and to try and improve it. What I've discovered is that there were many albums released during the months of July and August 1968--more so in terms of numbers of releases in a single month than in any previous month--so as you can see, August’s list is rather long (assuming the information I've come across is accurate). Here's the dozen albums I have put together for August 1968:

The Beach Boys, Stack-O-Tracks

The Bee Gees, Idea

Blue Cheer, Outsideinside

Country Joe & the Fish, Together

Donovan, In Concert

The Everly Brothers, Roots

The 5th Dimension, Stoned Soul Picnic

Fleetwood Mac, Mr. Wonderful

Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, You're All I Need

The Grateful Dead, [Two From the Vault] [8/23-24] [1992]

Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company, Cheap Thrills

Jeff Beck, Truth

Ten Years After, Undead

Wednesday, June 4, 2008

Gunslingers and Guitarschlongers

Last time I wrote about the significance of the album cover to Bo Diddley's Bo Diddley is a Gunslinger (Checker, 1960; pictured in the blog entry below). I observed that Bo Diddley wasn’t the first black musician to appropriate the iconography of the American West for an album cover; as Michael Jarrett has pointed out, jazz great Sonny Rollins did that, with Way Out West (Contemporary, 1957). Subsequently, the association of the popular musician with the myths of the American West--in particular, the musician as outlaw hero--became a significant one in the 1960s. I suggested that by appropriating the image of the outlaw hero for a generation of rock ‘n’ roll musicians, Bo Diddley became an iconic figure of rock 'n' roll, not simply a musical inspiration. Bo Diddley's album was released at the beginning of the 1960s. During the decade of the 60s, through a process that Robert Christgau calls a "barstool-macho equation of gunslinger and guitarschlonger," the musician as outlaw was formed, and his image, formerly associated with the values of the bohemian subculture, became, according to Michael Jarrett, "an icon recognized by all and embraced by many" (200). According to Robert Ray, the musician as outlaw stood for "freedom from restraint, a preference for intuition as the source of conduct, a distrust of the law, bureaucracies, and urban life" (255).

Last time I wrote about the significance of the album cover to Bo Diddley's Bo Diddley is a Gunslinger (Checker, 1960; pictured in the blog entry below). I observed that Bo Diddley wasn’t the first black musician to appropriate the iconography of the American West for an album cover; as Michael Jarrett has pointed out, jazz great Sonny Rollins did that, with Way Out West (Contemporary, 1957). Subsequently, the association of the popular musician with the myths of the American West--in particular, the musician as outlaw hero--became a significant one in the 1960s. I suggested that by appropriating the image of the outlaw hero for a generation of rock ‘n’ roll musicians, Bo Diddley became an iconic figure of rock 'n' roll, not simply a musical inspiration. Bo Diddley's album was released at the beginning of the 1960s. During the decade of the 60s, through a process that Robert Christgau calls a "barstool-macho equation of gunslinger and guitarschlonger," the musician as outlaw was formed, and his image, formerly associated with the values of the bohemian subculture, became, according to Michael Jarrett, "an icon recognized by all and embraced by many" (200). According to Robert Ray, the musician as outlaw stood for "freedom from restraint, a preference for intuition as the source of conduct, a distrust of the law, bureaucracies, and urban life" (255).

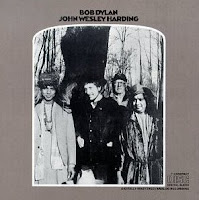

Outlaw iconography became a metaphor for individuality, integrity, and self-reliance. In addition  to albums such as The Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968) and the Eagles' Desperado (1972) that I mentioned last time, we can also add the following albums and songs. Perhaps a key album in the development of the popular musician as outlaw hero was Bob Dylan's John Wesley Harding (1967), in which he merged his own biographical details with the figure of the notorious Texas outlaw. Hence Jimi Hendrix's decision to cover "All Along the Watchtower" is much more deliberate than it at first may seem. The following list of albums with frontier imagery is not intended to be an exhaustive list, merely an indication of how widespread was the appropriation of the imagery of the American West.

to albums such as The Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968) and the Eagles' Desperado (1972) that I mentioned last time, we can also add the following albums and songs. Perhaps a key album in the development of the popular musician as outlaw hero was Bob Dylan's John Wesley Harding (1967), in which he merged his own biographical details with the figure of the notorious Texas outlaw. Hence Jimi Hendrix's decision to cover "All Along the Watchtower" is much more deliberate than it at first may seem. The following list of albums with frontier imagery is not intended to be an exhaustive list, merely an indication of how widespread was the appropriation of the imagery of the American West.

Duane Eddy - Have 'Twangy' Guitar, Will Travel (1958)

Bo Diddley - Have Guitar, Will Travel (1959)

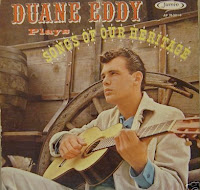

Duane Eddy - Songs of Our Heritage (1960)

Bob Dylan - John Wesley Hardin (1967)

Quicksilver Messenger Service - Happy Trails (1968)

The Flying Burrito Brothers - The Gilded Palace of Sin (1969)

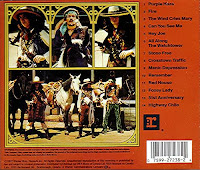

The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Smash Hits (1969) (back cover; pictured)

Mason Proffit - Wanted! Mason Proffit (1969)

The James Gang - Rides Again (1970) (and numerous other album titles)

Mason Proffit - Movin' Toward Happiness (1971)

War - The World is a Ghetto (with "The Cisco Kid") (1972)

Bob Dylan - Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973)

Willie Nelson - Red-Headed Stranger (1975)

Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Tompall Glaser, and Jessi Colter - Wanted! The Outlaws (1976)

Reggae musicians adopted the image of the outlaw hero as well: the late Jimmy Cliff with The Harder They Come (1972) and The Wailers with "I Shot the Sheriff" (1973). The so-called "Outlaw" movement in country music picked adherents as well, such as David Allan Coe, with his album Rides Again (1977). And, eventually, even a rock band from the American South named itself the Outlaws. The eponymous first album of the Outlaws was released in 1975, by which time the musician as outlaw was well over a decade old.

Saturday, February 16, 2008

Friday, January 15, 1960: Electric Guitar

This is the meaning of life

This is the meaning of life

To tune this electric guitar

--Talking Heads, “Electric Guitar”

According to Dik de Heer’s exhaustive In the Can page, on Friday, January 15, 1960, rock guitarist Duane Eddy completed the recording of his acoustic album Songs of Our Heritage, a strong candidate for rock music’s first “unplugged” album. Eddy, known for his “twangy” guitar—a 1956 Gretsch model 6120, aka a “Chet Atkins Hollow Body” (an example of this particular 1956 production model is pictured above)—had been extraordinarily successful with a series of rock instrumental albums in the late 1950s, beginning with the colossal best-seller, Have ‘Twangy’ Guitar—Will Travel, which entered the charts in January 1959 and remained there for the next 42 weeks. With Songs of Our Heritage (Jamie Records, 1960), he unplugged, performing a number of American folk tunes, including “John Henry,” “Streets of Laredo,” “Wayfarin’ Stranger,” “Mule Train,” and others.

Duane Eddy, along with guitarists such as Link Wray (who in contrast to Eddy’s “twangy” guitar played a “fuzzy” or distorted guitar) and, later, Dick Dale, eroticized the electric guitar, transforming it into a hypermasculine symbol of phallic power. Eddy’s “Rebel Rouser” and Wray’s “Rumble” were much more than rock instrumentals featuring the electric guitar: the guitar became a signifier of masculine rebellion. (There’s a direct link, for instance, from Wray’s “Rumble” to Steppenwolf’s “Born to be Wild,” as both are “biker” favorites.) The Who’s Pete Townshend has said that he was compelled to learn the guitar because of Link Wray’s “Rumble.” Likewise, John Fogerty of Creedence Clearwater Revival said he picked up the guitar because of the bold image of Duane Eddy standing before his band, his authority determined by the fact that he wielded the scepter-like electric guitar. In retrospect, Jimi Hendrix’s act of setting his guitar on fire at the end of his performance at the Monterey Pop Festival seven years later seems not so much a “sacrifice” in the ritual (religious) sense as it is an act of self-emasculation. Sigmund Freud would no doubt be compelled to explore the question as to why no guitar heroes in rock music have ever been female. He'd probably give the same answer as he did in Civilization and Its Discontents in his speculations as to why women are no good with baseball bats.

The album cover of Songs of Our Heritage reveals the extent to which rock musicians (and hence rock music) consciously or unconsciously identified itself  with a certain set of distinctive values (among them, the American frontier) all of which helped distinguish it from Pop. According to Mike Jarrett’s wonderful Sound Tracks: A Musical ABC, Vols. 1-3 (Temple University Press, 1998), a book I find myself returning to again and again, rock music has defined itself against pop by a number of associations derived from the signifer of the guitar. I’ve only listed a few of these structural oppositions here from Jarrett’s more comprehensive list (pp. 68-69 in his book):

with a certain set of distinctive values (among them, the American frontier) all of which helped distinguish it from Pop. According to Mike Jarrett’s wonderful Sound Tracks: A Musical ABC, Vols. 1-3 (Temple University Press, 1998), a book I find myself returning to again and again, rock music has defined itself against pop by a number of associations derived from the signifer of the guitar. I’ve only listed a few of these structural oppositions here from Jarrett’s more comprehensive list (pp. 68-69 in his book):

ROCK/POP

guitars/keyboards

frontier/civilization

experience/knowledge

rural/urban

masculine/feminine

spontaneity/calculation

genuine/artificial

raw/cooked

America/Europe

vigorous/effete

To which one might “hard” and “soft,” as in “hard rock” vs. “soft rock” (i.e., “pop,” sometimes derisively referred to as “bubblegum,” the later associated with “boys” or "boy bands" rather than “men.”) The symbolic underpinnings of this structural opposition hardly need to be made explicit.

In response to what I anticipate to be the many objections the psychoanalytic approach I’ve employed here, I’ll simply point out the way certain American filmmakers subsequently appropriated this music for the aural backdrop in films exploring hypermasculine violence (its later use proves the point). Oliver Stone used “Rebel Rouser” in Natural Born Killers, while Quentin Tarantino used Dick Dale’s “Misirlou” and Wray’s “Ace of Spades” and “Rumble” in Pulp Fiction. And David Lynch has used the so-called “dirty boogie” inspired by Link Wray for songs such as “Blue Frank." Have a listen "Blue Frank," included on the Twin Peaks: Season 2 soundtrack, that was used in Fire Walk With Me during the Partyland scenes, the corresponding sonic counterpart to scenes of eroticized violence.