My previous blog entry, “The Sentimental Lunatic,” on the song "Everyone's Gone to the Moon," prompted my friend Tim Lucas to post an interesting comment, which can be found at the end of that blog (portions of it are reproduced below). His response prompted me to reflect on some issues I raised in that blog, which I’d like to expand on, briefly, with this post. For the sake of convenience I’ve reproduced Tim’s response below, splitting it into two parts in order to discuss two distinct issues. I reproduce the first half of his comment here:

My previous blog entry, “The Sentimental Lunatic,” on the song "Everyone's Gone to the Moon," prompted my friend Tim Lucas to post an interesting comment, which can be found at the end of that blog (portions of it are reproduced below). His response prompted me to reflect on some issues I raised in that blog, which I’d like to expand on, briefly, with this post. For the sake of convenience I’ve reproduced Tim’s response below, splitting it into two parts in order to discuss two distinct issues. I reproduce the first half of his comment here:

... My own take on it [“Everyone’s Gone to the Moon”] is quite different, and simpler, than yours. To my thinking, the song sketches a moment in Swinging London’s history when the scene began to darken as harder drugs than marijuana, like cocaine and heroin, came into fashion. Consequently the lyrics are organized to depict various pleasures in contrast with their own cancellation or contradiction, painting a world of plenty that still exists but is beyond the reach of people who are perpetually zonked (e.g., “gone to the moon”), with strength enough only to “lift a spoon.”

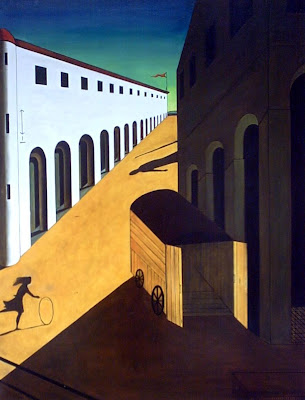

His notion that the song is a response or reaction to the darker side of the “Swinging London” scene is very plausible. In my own discussion of the song, I explored the way the song corresponded, in a rather remarkable way, to what Louis A. Sass, in his book Madness and Modernism, calls the schizophrenic Stimmung, or the onset of the radically altered perception of reality that accompanies a schizophrenic break. My own view is that while the song ostensibly offers itself as a quasi-mystical insight into the nature of reality, on closer inspection it is actually closer to an anti-epiphany, an insight into reality that may be true, but one that is terrible or nightmarish rather than positive. I therefore included some image files of paintings by the severely schizoid painter, Giorgio de Chirico, in order to provide a sort of visual equivalent of the perceptual alteration of the world that characterizes the anti-epiphany (supported musically, incidentally, by the song fading out to the discordant sounds of violins being played out of tune).

It seems to me, though, that Tim’s view and my view are not incompatible, just focused differently, his narrowly on the immediate social context in which the song was made, and mine more broadly, on the subjective response to a rapidly changing world of ever-increasing complexity, a response that Alvin Toffler would characterize in the title of a book, published only a few years later, as “future shock”:

Streets full of people all alone

Roads full of houses never home

Church full of singing out of tune

Everyone’s gone to the moon

Eyes full of sorrow never wet

Hands full of money all in debt

Sun coming out in the middle of June

Everyone’s gone to the moon

Long time ago, life had begun

Everyone went to the sun

Cars full of motors painted green

Mouths full of chocolate covered cream

Arms that can only lift a spoon

Everyone’s gone to the moon

My best estimate is that the song was recorded ca. April 1965, thus making it a bit too early to be considered psychedelia, although lyrically speaking it shares features with that form of music. Still, most psychedelia is more benign, more epiphanic, than “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon” (as evidenced by psychedelia’s transformation, as I’ve argued in previous posts on this blog, into bubblegum music). The last set of lyrics, beginning with “Cars full of motors painted green...,” seems especially directed toward a certain “social type” (following Tim’s interpretation), one whose life is composed of affected pretensions and effete mannerisms, and also one of privileged self-indulgence. Indeed, the “Swinging London” of the 60s has been characterized as an unusual mélange of slumming aristocrats and posturing hippies. Along these lines, the aforementioned lyric referring to “Cars...painted green” struck me as a possible oblique reference to John Lennon’s Rolls-Royce Phantom V which Lennon had re-painted in psychedelic colors, but according to this website, Lennon didn’t acquire the Roller until 3 June 1965, and it wasn’t repainted in psychedelic fashion until April 1967—long after “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon” was recorded.

Speaking of historical dating, I’ll return to Tim’s response. Here is most of the second half:

It could even be a criticism of then-fashionable acid rock, given the lines about how “long time ago, life had begun/everyone went to the sun,” which reads to me as an allusion to Brian Wilson, The Beach Boys, and their fun- and life-affirming brand of rock. Indeed, given the fact that The Beach Boys were contemporaneously releasing their masterpiece Pet Sounds, criticized at the time as too downbeat by some, the song could almost be interpreted as a direct criticism of the “moon” music emerging from Brian Wilson's withdrawal into coke and LSD.

Appropriately, Tim brought up a lyric of the song I hadn’t discussed, but allow me to correct him on one factual point before I continue: Pet Sounds wasn’t released until May 1966, almost a year after “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon” had charted in the UK. However, and more importantly, I think he’s correct to associate the reference, “everyone went to the sun,” with American West Coast (“surf”) music such as that played by the Beach Boys, and with California in general. For me, the song that immediately comes to mind in this context, though, and which preceded “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon,” is The Rivieras’ 1964 hit, California Sun. According to this source, “California Sun,” which appeared on the pop charts early in 1964, was one of the last chart-topping songs by an American band on the Billboard Hot 100 chart before the so-called “British Invasion.” And according to another source, "California Sun" would have reached the No. 1 spot on the pop charts if it hadn't been displaced by the Beatles' "I Wanna Hold Your Hand." If this information is correct, then the lyric, “long time ago, life had begun/everyone went to the sun,” can be understood as referring to a time prior to the “British invasion,” the time of the popularization of rock 'n' roll by Elvis (“sun” as in Sun Records, Elvis’s first record label) and American rock ‘n’ rollers such as Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, The Rivieras, and of course the Beach Boys, displaced by (among others) the Beatles—and even, ironically, “British invasion” songs such as “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon.”

When I set out to discuss "Everyone's Gone to the Moon," I hadn't expected to encounter the richly allusive density of the lyrics. However, thanks to comments such as the one by Tim Lucas, the song is vastly richer than I had ever imagined. Although I frequently curse the amount of time it takes to maintain a blog, it's frequently the case that because I took the time to sit down and write about a particular topic, I end up learning a great deal, much more than I'd imagined, as I did in this case, when writing about the aforementioned song.

Sunday, May 4, 2008

Moonstruck

Friday, May 2, 2008

The Sentimental Lunatic

I think Jonathan King’s “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon,” which reached the Top 4 spot in the UK pop charts in late July 1965, is a beautiful song; its aching melancholy has haunted me for decades. I must have been around eleven years old when I first heard it, and I simply can't shake it off. But what is it about? Like a startling image from a strange dream, it remains firmly lodged in my memory, because its strangeness is precisely what makes it so difficult to forget. Many people, I’ve found, have had an odd or unusual dream that they’ve never been able to forget, primarily because they’ve never been able to explain it satisfactorily, if at all.

I think Jonathan King’s “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon,” which reached the Top 4 spot in the UK pop charts in late July 1965, is a beautiful song; its aching melancholy has haunted me for decades. I must have been around eleven years old when I first heard it, and I simply can't shake it off. But what is it about? Like a startling image from a strange dream, it remains firmly lodged in my memory, because its strangeness is precisely what makes it so difficult to forget. Many people, I’ve found, have had an odd or unusual dream that they’ve never been able to forget, primarily because they’ve never been able to explain it satisfactorily, if at all.

And yet, while the song is dream-like by virtue of its apparently stubborn resistance to interpretation, it also gives one the strong impression of being a quasi-mystical insight into the nature of modern life. In addition, its writer seems distinctly modern as well, self-consciously aware of his own mode of awareness, a representative of Schiller’s “sentimental” or “reflective” poet, the kind of writer who is “self-divided because self-conscious, and so composes in an awareness of multiple alternatives, and characteristically represents not the object in itself, but the object in the subject.” (See M. H. Abrams, Natural Supernaturalism, Norton, 1971, pp. 213-14.) In his discussion of literary scholar Joseph Frank’s classic essay, “Spatial Form in Modern Literature” (1945), Louis A. Sass, in his brilliant book, Madness and Modernism (Basic Books, 1992), writes:

...Joseph Frank describes some of the ways modernist fiction attempts to deny its own temporality and approach the condition of the poetic image, defined by Ezra Pound as “that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time.” To achieve this sense of encompassing experiential stasis, writers use a number of devices to draw attention away from both the inherent temporality of language (which by its very nature can only represent one word after another, in a temporal sequence) and the implicit temporality of human action itself, with its purposes and causes. These include: the overwhelming of plot by mythic structures used as organizing devices (as in Joyce’s Ulysses), the movement from perspective to perspective instead of from event to event (for example, Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury), and the use of metaphoric images as recurring leitmotifs to stitch together separate moments and thereby efface the time elapsed between them (for example, Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood). (34)

At least two of the features of modernist fiction as described above are employed in the lyrics to “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon”: the movement from one subjective perspective to another ("the object in the subject"), and the use of the recurring, metaphorical leitmotiv--the title itself. I reproduce here the lyrics in what I believe to be the accurate form:

Streets full of people all alone

Roads full of houses never home

Church full of singing out of tune

Everyone’s gone to the moon

Eyes full of sorrow never wet

Hands full of money all in debt

Sun coming out in the middle of June

Everyone’s gone to the moon

Long time ago, life had begun

Everyone went to the sun

Cars full of motors painted green

Mouths full of chocolate covered cream

Arms that can only lift a spoon

Everyone’s gone to the moon

It is necessary to go about living in the world, wrote the severely schizoid painter Giorgio de Chirico, “as if in an immense museum of strangeness.” Earlier I described “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon” as suggesting “a quasi-mystical insight,” but perhaps it is more accurately described as an anti-epiphany, which Louis A. Sass defines as, “an experience in which the familiar has turned strange and the unfamiliar familiar, often giving the person the sense of déjà vu and jamais vu, either in quick succession or even simultaneously.” (44) Sass observes that de Chirico took from Nietzsche the untranslatable German word Stimmung to describe the schizophrenic anti-epiphany, which he sees so evocatively captured in de Chirico’s painting Gare Montparnasse (Melancholy of Departure) (1914, pictured above at the top of this entry). “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon” seems very much like the experience of the schizophrenic Stimmung as described by Sass:

Unreality—“a universe of uniform precision and clarity but devoid of the dynamism, emotional resonance, and sense of human purpose that are characteristic of everyday life” (47). In order to illustrate the experience of Unreality, Sass cites the memoir of a schizophrenic named “Renee” to sufficiently capture the disturbing nature of the changed world: “It was...a country, opposed to Reality, where reigned an implacable light, blinding, leaving no place for shadow; an immense space without boundary, limitless, flat; a mineral, lunar country, cold as the wastes of the North Pole” (47).

Roads full of houses never home

Church full of singing out of tune

...

Eyes full of sorrow never wet

Hands full of money all in debt

Renee’s use of “lunar country” is provocative in this context, since the Latin word for “moon” is “luna,” the root of the word “lunatic” (slang: “loonies”), one who is crazy, insane, mad (moonstruck), suffering from “moon madness.” The association of moon and madness is, of course, invoked in Pink Floyd’s “Brain Damage” from Dark Side of the Moon (“The lunatic is on the grass”). Thus we are invited to interpret “everyone’s gone [to the moon]” as “everyone’s gone [mad],” everyone has gone “looney.”

Mere Being—Sass again refers to the memoir of “Renee,” observing: “At other times what astonished Renee...was not so much the absence of a normal sense of authenticity, emotional resonance, or functional meanings, but the very fact that objects existed at all—their Mere Being. Here we encounter an experience so very general in nature, yet at the same time so inherently concrete, so rooted in the mute thereness of the world, as nearly to defy description....such experiences can be akin . . . to the exalting feeling of wonder, mystery, and terror....” (48) (See the de Chirico painting above, Melancholy and Mystery of a Street, 1914.)

Streets, Roads, Church, Eyes, Hands, Sun, Cars...painted green, Mouths, Arms, Motors, Spoon

Fragmentation—“Objects normally perceived as parts of larger complexes may seem strangely isolated, disconnected from each other and devoid of encompassing context; or a single object may lose its perceptual integrity and disintegrate into a disunity of parts.... Another schizophrenic likened his vision of Fragmentation to being ‘surrounded by a multitude of meaningless details.’ ‘I did not see things as a whole,’ he said, ‘I only saw fragments: a few people, a dairy, a dreary house’ (49-50).

Streets full of people all alone

...

Cars full of motors painted green

Mouths full of chocolate covered cream

Arms that can only lift a spoon

Apophany—From the Greek word apophany, meaning “to become manifest.” “Once conventional meanings have faded away (Unreality) and new details or aspects of the world have been thrust into awareness (Fragmentation, Mere Being), there often emerges an inchoate sense of the as yet unarticulated significances of these newly emergent phenomena. In this “mood,” so eerily captured in both the writings and the paintings of de Chirico, the world resonates with a fugitive significance. Every detail and event takes on an excrutiating distinctness, specialness, and peculiarity—some definite meaning that always lies just out of reach, however, where it eludes all attempts to grasp or specify it” (52). In short, every single image implies an elusive “meaning” that lies "just out of reach."

E.g., Arms that can only life a spoon

What is the peculiar specialness, elusiveness, meaning of the utterance, Arms that can only lift a spoon? Decadent, effete behavior? An effect of life in zero-gravity, of living in outer space? The arm of a drug addict (the spoon associated with the intravenous administration of heroin)? Infantile behavior, in the sense that the spoon is the first utensil employed by humans ("spoon-fed")?

Additionally, Sass argues that in modernist art "the post-Kantian awareness of the limitedness of perspective engenders contradictory urges and futile yearnings, cravings to explore unimaginable viewpoints, uninhabitable mental climes," resulting in what he calls a "crossfade technique," in which "two objects or domains [are] so interfused that they seem to have merged, creating a single object that could exist nowhere but in some mental or inner universe...." (137). The entire song works this way, but is exemplified by lyrics such as:

Eyes full of sorrow never wet

Hands full of money all in debt

Sun coming out in the middle of June

Hence "Everyone's Gone to the Moon" might be best understood as a sort of cubist or futurist collage, a heteroclite mélange of "perspectival fluctuations" very similar, as Sass would argue, "to what occurs with schizophrenia" (138).

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

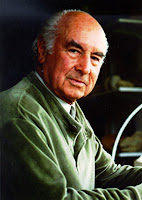

Albert Hofmann, 1906-2008

Albert Hofmann, the Swiss chemist who devised the technique to make derivatives of lysergic acid and who eventually synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), has died of heart failure at the ripe old age of 102.

Albert Hofmann, the Swiss chemist who devised the technique to make derivatives of lysergic acid and who eventually synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), has died of heart failure at the ripe old age of 102.

Hofmann was a chemist at the Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland, when in the late 1930s he turned to the study of ergot, the name for a fungus that grows on rye, barley and certain other plants. Studying the active ingredient of ergot, a chemical identified by American researchers in the 1930s as lysergic acid, Hofmann invented a method to synthesize a series of compounds of that substance. The 25th one he synthesized was lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD-25. As is well known, he subsequently, in 1943, became the first person to take an acid trip. LSD-25, Hofmann’s so-called “problem child” as he referred to his creation in his autobiography, subsequently influenced an entire generation, and had a profound influence on the lives of individuals such as Timothy Leary.

Thus Albert Hofmann can be understood as an author, although not necessarily an author of the novelistic sort (he did, though, author numerous scientific articles). In calling Albert Hofmann an author, I have in mind Michel Foucault’s essay, “What Is an Author?,” and his discussion of an uncommon but profound kind of author that Foucault named a “founder of discursivity.” About such authors, Foucault wrote:

They are unique in that they are not just the authors of their own works. They have produced something else: the possibilities and the rules for the formation of other texts. In this sense, they are very different, for example, from a novelist.... Freud is not just the author of The Interpretation of Dreams or Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious; Marx is not just the author of the Communist Manifesto or Capital: they both have established an endless possibility of discourse.... the initiation of a discursive practice is heterogeneous to its subsequent transformations. To expand a type of discursivity, such as psychoanalysis as founded by Freud, is not to give it a formal generality that it would not have permitted at the outset, but rather to open it up to a certain number of possible applications. (See Josue V. Harari, Textual Strategies, Cornell University Press, 1979, p. 154-56.)

Albert Hofmann was an author of the sort Foucault outlines here: he enabled and initiated the creation of many other texts, in film, literature, art, and perhaps most especially, in music--particularly the form of music that developed in the 1960s, psychedelia. Hence Albert Hofmann can be understood as one of the more significant and influential authors of the twentieth century, and perhaps should be remembered as such.

A compelling obituary can be found here.

Are You Experienced (Enough)?

Several news articles have appeared on the web this morning claiming that a roughly 11-minute video has been released for sale on the internet that shows the late Jimi Hendrix having sex with two women “in a dimly lit bedroom.”

Several news articles have appeared on the web this morning claiming that a roughly 11-minute video has been released for sale on the internet that shows the late Jimi Hendrix having sex with two women “in a dimly lit bedroom.”

Although the DVD version (and perhaps the version available for download, I don't know) apparently contains the testimony of two former Sixties groupies—one the well-known fellatrix Pamela Des Barres, the other Cynthia Albritton aka “Cynthia Plaster Caster” averring the authenticity of the footage—there is every reason to believe the video is a hoax, as “authentic” as the video purportedly containing footage of an alien autopsy. Whether Jimi Hendrix indulged in the ménage is not the issue here; I’ll leave that for others to fret over (assuming it makes any difference to anyone). However, the reasons for my suspicion that this video is a hoax are as follows:

1. Anecdotal Evidence:

A.) Vivid Entertainment Group (VEG) averred “in a press release” (i.e., a photocopied sheet of paper, not a sworn affidavit) that they consulted with many “experts.” Experts on what? The anatomy of Jimi Hendrix? (Are there such experts?) The period authenticity of the putative source materials, the alleged film footage—it was the pre-video time period, remember, when the footage was shot? The décor, meaning they can ascertain whether the location was Britain or America by means of furniture, wall fixtures, etc.? The aforementioned former groupies are among the so-called experts. VEG’s claim is that the former groupies, more so than anyone, ought to recognize the genitals of someone with whom they were intimate, even if that intimacy (of whatever sort) was forty years ago. After all, claims VEG, their chosen area of expertise was male genitalia.

B.) Vague, questionable provenance: Some news articles refer to a “tape,” although again if the event recorded actually took place forty years ago, it is highly unlikely that the footage was shot on video, but more likely film (one article I read did in fact refer to “8mm footage”). VEG purchased the “tape” from an individual named Howie Klein, who brought the “tape” to Vivid after he, Klein, acquired it from a collector “who found it.” How and where was it found? Where has the footage been stored for the past forty years, and how was it discovered? Who is the unidentified “rock and roll memorabilia collector” referred to in some news articles, and how did he (or she) acquire it? What was the method by which Mr. Klein authenticated the “tape”--or film--prior to purchasing it? Who is the cameraman who claims to have shot the footage? Why and under what particular circumstances was he hired (or designated) to do so? If the material object in question were a painting rather than very easily faked video footage, would its authenticity be unquestionably guaranteed by such a dubious provenance?

C.) The location of the ménage, “a dimly lit bedroom,” smacks of the “unidentified location” where, for instance, the alien autopsy took place. Moreover, the fact that the bedroom is "dimly lit" is suspicious, as it makes the identity of the individuals in the scene more difficult to determine. VEG claims the footage is forty years old, but unless the 8mm footage can be produced and can be subject to the same intense scrutiny as the Zapruder footage of the Kennedy assassination, VEG's claim has the same truth value as an opinion of belief.

D.) VEG lawyers allegedly hired “private investigators” to track down the man who claims to have been the cinematographer of the event. Even if this is true, it doesn’t “authenticate” the footage. There have been individuals over the years swearing to have seen dead alien bodies after the supposed Roswell UFO crash. Neither lawyers nor private investigators have access to the private contents of a person’s mind; all they can do is verify the actual identity of the person making the claim, and verify that this person, so identified, swears (believes) he or she is telling the truth about the matter. An individual may swear he or she is telling the truth about seeing the body of a dead alien, but this does not prove whatsoever the existence of the alien body. As many studies of perceptual cognition have revealed, what one sees isn't simply a matter of sensory apparatus (the eyes), but what thinks one sees (think of the famous example of the "duck-rabbit"). Perceptual ambiguity is precisely the issue here: who is that person in the footage?

2. Counter-Evidence:

A.) Kathy Etchingham, Jimi Hendrix’s long-time girlfriend, after viewing several still photographs of the footage, has told several newspapers, “It is not him.” Doesn’t she qualify as an expert?

B.) Charles R. Cross, author of the excellent Hendrix biography Room Full of Mirrors, who saw the footage while he was researching his book and dismissed it at the time as fake, also disputes the identity of the man in the "tape," claiming among other things that Hendrix was too painfully shy to have agreed to perform sexual acts on camera. Like Kathy Etchingham, he also claims the person is not Hendrix. Doesn’t he qualify as an expert? The fact that Mr. Cross saw the footage while researching his biography means the existence of the footage has been known for, at the very least, four years (the hardcover edition of his biography was published in 2005), and perhaps longer, but no one took it seriously.

C.) At the time (ca. 1968), most enthusiasts purchased unexposed negative for 8mm cameras in the form of cartridges containing a film spool three minutes in length. While it is possible the alleged footage could have been shot using several such cartridges, the color film in each cartridge, unless the conditions were extremely well-controlled, often would often develop with minor differences in contrast levels and color saturation. I haven’t seen the footage of the menage, but if it consists of one uninterrupted eleven-minute sequence, it’s likely faked. However, someone trying to pull off a clever hoax, knowing how amateurs purchased 8mm film stock at the time, might well have used computer technology to imitate different color and contrast levels in roughly three-minute segments.

3. Legal Status of the Footage:

A spokesman for Experience Hendrix, the Seattle company owned by Hendrix’s relatives that controls the rights to his music, said, “We’re in no position to verify [the tape’s authenticity],” meaning his company doesn’t claim to have anyone on staff with the competency (expertise) to very the authenticity of the footage--in contrast, to, say, VEG--meaning the company isn't saying one way or the other. The company's denial of expertise thus enables VEG legally to distribute the footage because as far as VEG is concerned, the person being filmed doesn’t have to be really Hendrix anyway, but merely a person possessing “Hendrix’s likeness.” Surprisingly, it seems that the rights to Hendrix’s likeness remains an unsettled legal issue--the loophole necessary to have enabled VEG to distribute the video.

Monday, April 28, 2008

The Reassurance of Fratricide

The title of my entry is taken from Benedict Anderson’s book, Imagined Communities (Revised Edition, Verso, 1991), and his discussion of memory and forgetting, that is, the way the writing of history constitutes an act that consists both of remembering (anamnesis) and its opposite, amnesia. Since history is written by the victors, the Civil War, for example, is consequently the enactment of the hostility of “brother against brother,” that is, the story of Cain and Abel (hence the inspiration for his homiletic parody, "the reassurance of patricide"). Had the Confederacy won, however, it might well have been about something, speculates Anderson, "quite unbrotherly" (201).

The title of my entry is taken from Benedict Anderson’s book, Imagined Communities (Revised Edition, Verso, 1991), and his discussion of memory and forgetting, that is, the way the writing of history constitutes an act that consists both of remembering (anamnesis) and its opposite, amnesia. Since history is written by the victors, the Civil War, for example, is consequently the enactment of the hostility of “brother against brother,” that is, the story of Cain and Abel (hence the inspiration for his homiletic parody, "the reassurance of patricide"). Had the Confederacy won, however, it might well have been about something, speculates Anderson, "quite unbrotherly" (201).

Fratricide: the story of brother against brother, the mythic archetype of Cain and Abel. Elvis Costello wrote “Blame it on Cain,” but I choose to blame it on Elvis, primarily for the act of fratricide that drives the plot of his first movie, Love Me Tender (1956). In his first film role, Elvis played Clint Reno, who during the Civil War remained home while his older brother, Vance (Richard Egan), fought on the side of the Confederacy. At war’s end, Vance returns home to discover that during his absence his former beloved, Cathy (Debra Paget), has married his brother Clint. But...there is an alibi, or excuse, for this state of affairs, because Clint and Cathy had been told that Vance had been killed in battle. Predictably, as one might expect, the story moves inexorably toward its tragic conclusion, foregrounded as it is by brotherly strife.

Since Elvis, or perhaps because of Elvis, there have been many songs reenacting, in various guises, the story of Cain and Abel. Here are a few representative recordings:

The Boomtown Rats, "I Don't Like Mondays"

The Buggles, “Video Killed the Radio Star”

Johnny Cash, “Frankie and Johnny” & “Folsom Prison Blues”

The Doors, “The End” (parricide) & “Riders on the Storm”

The Eagles, “Doolin-Dalton”

Lefty Frizzell, “Long Black Veil”

Lorne Greene, "Ringo"

Jimi Hendrix, “Hey Joe”

Robert Johnson, "32-20 Blues"

The Kingston Trio, “Tom Dooley”

Vicki Lawrence, “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia”

The Louvin Brothers, “Knoxville Girl”

Bob Marley, “I Shot the Sheriff”

Crispian St. Peters, “The Pied Piper”

Pink Floyd, "Careful With That Axe, Eugene"

Gene Pitney, "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance"

Stan Ridgway, “Peg and Pete and Me” & "Down the Coast Highway"

Marty Robbins, “El Paso" & "Big Iron"

Jimmy Lee Robinson, “I Shot a Man”

Kenny Rogers and the First Edition, “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town”

The Rolling Stones, “Midnight Rambler”

Bruce Springsteen, “Nebraska”

Hank Snow, “Miller’s Cave”

Suicidal Tendencies, “I Shot the Devil”

Talking Heads, “Psycho Killer”

Hank Williams, Jr., “I’ve Got Rights”

Neil Young, “Down by the River” & “Southern Man”

Saturday, April 26, 2008

(Do What You Can Do) Then Move On

A Klee painting named “Angelus Novus” [1920; pictured] shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

A Klee painting named “Angelus Novus” [1920; pictured] shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

--Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (Trans. Harry Zohn)

If Robert B. Ray is correct, we live in an age characterized by a longing for missed opportunities, the age of the catastrophe. Citing Walter Benjamin’s definition of catastrophe—“to have missed the opportunity”—the late twentieth century (and early twenty-first) seems to be an age that pines excessively for lost opportunities, and so longs for omnipotence, for “extensive presence” (15). While Robert Ray’s specific subject in his essay is the origins of photography and its subsequent social impact, the same longing for the unattainable is a persistent feature of the discourse about popular music, for that presumed unrecoverable "lost album"--to have everything. For instance, what masterpiece was lost when Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys’ Smile was destroyed by flames? What music was left unmade as a consequence of the murder of John Lennon? What albums might have Brian Jones made, or Jimi Hendrix? What would have been the musical response by Buddy Holly upon hearing the Beatles? If only...

What prompted these musings was my reading of Andrew Sandoval’s informative liner notes to the just released 2-CD "Collector’s Edition" of Love’s Forever Changes (1967), and his discussion of a rumored lost album by the original lineup of Love, titled Gethsemane. Sandoval writes:

Though [Arthur] Lee fronted several versions of Love in the years that followed [Forever Changes], rumors of a lost album by the original lineup (the mythical Gethsemane) continue to circulate. “There was no Gethsemane,” said Lee in 2002. “There’s no such thing as that stuff. I don’t know any of those songs. I couldn’t take it anymore. I couldn’t take being around those guys anymore. There’s no album.”

Mythical elaboration often develops around something about which little is known or understood, in this case a rock band whose definitive lineup didn’t cohere as a group of musicians very long (not that this phenomenon is unusual in the history of rock music; on the contrary, it’s a commonplace). What interested me was the supposed “lost album” titled Gethsemane, whose putative existence I hadn’t heard about before, but that’s not the point. The putative existence of this “lost album” is an example of an excessive, unhealthy pining for a supposed missed opportunity, the catastrophe represented by the image of unreleased masters buried in the wreckage of Time and History.

It is, of course, a grand myth, the Romantic myth of lost, or perhaps neglected, genius, but it is an elusive genius in that it is presupposed on the existence of music that no one has ever heard. The idea is amusing, in that it presumes that the vast majority of mere mortals are either, 1) “not ready” for it or, 2) if they were, wouldn’t have fully comprehended it anyway. But as an idea it is also repulsive, because it presupposes a colossal act of genius that the previously published work simply doesn't support (or anticipate). Moreover, in its actual manifestation, the work could never match the simulacrum of it one has constructed in one's imagination. Of course, none of these realities have prevented the aforementioned Romantic myth from becoming a foundational myth of rock criticism.

We need to move beyond a constant yearning for the unattainable, the continual longing for the missed opportunity—the catastrophe—which is really a sublimated religious impulse that demands of this woefully banal world something that it cannot give to, or provide for, us. Writing in The New Rolling Stone Record Guide (Dave Marsh and John Swenson, Eds., Random House/Rolling Stone Press, 1983), John Swenson observed of The Beatles:

In retrospect, the group’s much-lamented decision to call it quits as the Seventies began was entirely appropriate; the collected work does not leave you with the impression that there were unfinished statements....They did it all, they did it right, and then they went their separate ways. (32)

The vanished band members of popular music history did what they could do, and then moved inexorably on, moving on through the garden of forking paths. There has been no catastrophe, and never was. (Or rather, if there has been, it lies in the particular circumstance surrounding their premature deaths.) The lesson for all of us: Do what you can do, and then move on, just as they did. Let the dead bury the dead. We shall all hear the incomparable music of the heavenly choir much sooner than we think--or wish.