At Bonhams New York this past Wednesday, May 14, The Peter Golding Collection of Rock & Roll Art fetched close to $795,000, according to a spokesman for the auction house. While many of the pieces were original works of art, some of the items included preliminary drawings and sketches for album covers and concert posters. The Peter Golding collection represents about forty years of collecting such work; Golding is the British designer of the first stretch jeans. Go here for a closer look at the 164 lots offered at the auction. The auction's top seller was an 48"x36" acrylic on canvas by the late Rick Griffin--considered by some to be psychedelia's grand master--for the Grateful Dead's 1990 "Without a Net" European tour, which sold for $114,000; go here to see the piece.

At Bonhams New York this past Wednesday, May 14, The Peter Golding Collection of Rock & Roll Art fetched close to $795,000, according to a spokesman for the auction house. While many of the pieces were original works of art, some of the items included preliminary drawings and sketches for album covers and concert posters. The Peter Golding collection represents about forty years of collecting such work; Golding is the British designer of the first stretch jeans. Go here for a closer look at the 164 lots offered at the auction. The auction's top seller was an 48"x36" acrylic on canvas by the late Rick Griffin--considered by some to be psychedelia's grand master--for the Grateful Dead's 1990 "Without a Net" European tour, which sold for $114,000; go here to see the piece.

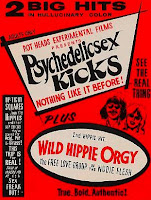

One of the more interesting items for sale was an exhibitor's brochure for the movies Psychedelic Sex Kicks and Wild Hippie Orgy, presented by "Pot Heads Experimental Films." The brochure's cover promises "2 Big Hits" in "Hullucinary Color" [sic]. If you always wanted to own the item, you still have a chance--although the brochure was estimated to go between $150-250, it didn't sell. The films boast scenes in which "Up-tight squares join the hippies and their hip chicks...this trip is for real!"

Sunday, May 18, 2008

Art of Rock

By Hook or by Crook

What’s the difference between a hook and a ditty? Available definitions don’t offer much help, I’ve discovered. The following definitions are available from answers.com:

What’s the difference between a hook and a ditty? Available definitions don’t offer much help, I’ve discovered. The following definitions are available from answers.com:

Hook (n.):

1. a. A curved or sharply bent device, usually of metal, used to catch, drag, suspend, or fasten something else.

b. A fishhook.

2. Something shaped like a hook, especially:

a. A curved or barbed plant or animal part.

b. A short angled or curved line on a letter.

c. A sickle.

3. a. A sharp bend or curve, as in a river.

b. A point or spit of land with a sharply curved end.

4. A means of catching or ensnaring; a trap.

5. Slang. a. A means of attracting interest or attention; an enticement: a sales hook.

b. Music. A catchy motif or refrain: “sugary hard rock melodies [and] ear candy hooks” (Boston Globe).

Ditty (n., pl. –ties):

A simple song.

[Middle English dite, a literary composition, from Old French dite, from Latin dictātum, thing dictated, from neuter past participle of dictāre, to dictate.]

So apparently the word “ditty” refers to a complete song, while “hook” refers to a rhythmic figure or melodic line, that is, a specific element of a song. So is a ditty (song) necessarily composed of more than one hook, or just one? To me, anyway, the origin of the word “ditty” from the Latin dictātum (“thing dictated”) suggests that a ditty is easy to remember (“simple”). Information theory would then tell us that a ditty has a low probability of being transmitted incorrectly (“distorted”), another way of saying it is easily remembered: how many times did you have to hear “Happy Birthday” before you remembered the whole song? Once? The popular TV game show Name That Tune is premised precisely on this insight, that one needs only a few notes in order to have total recall of a song. (I best remember the version of the show in the Seventies hosted by Tom Kennedy, but historically there have been several incarnations of Name That Tune, beginning in the 1950s.)

Are the best pop songs, then, no more than ditties? According to Gary Burns, in “A typology of ‘hooks’ in popular records” [Popular Music 6:1 (Jan., 1987) p. 1], the word hook

connotes being caught or trapped, as when a fish is hooked, and also addiction, as when one is hooked on a drug. These connotations, together with the idea of repetition, are captured in the Songwriter’s Market definition of hook: ‘A memorable “catch” phrase or melody line which is repeated in a song’ (Kuroff 1982, p. 397. Bennett (1983) defines hook as an ‘attention grabber’ (pp. 30, 41).

Music critic Lester Bangs was never comfortable with the multiple connotations of hook as “catchy,” meaning hook as that which catches or ensnares the prey, is addictive, and is seductive and appealing as candy. He wrote:

Listen, I hate hooks. The first time I saw the word “hook” was in a review of a Shocking Blue album in Rolling Stone in 1969. The author had evidently discovered that songwriters sometimes used it and now informed us that the bass riff was the almighty “hook” in their hit “Venus,” that one irresistible little melodic or rhythmic twist that’ll keep you just coming back and back and back and buy and buy and buy. (“Every Song a Hooker,” in Mainlines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste: A Lester Bangs Reader, Anchor Books, 2003, pp. 351-52)

Freud argued that repetition is pleasurable because we associate it with the pleasure of the mother’s breast (or bottle) from which we nursed (sucked, in the sense of reiterated action) as infants. Whether one believes this argument is irrelevant, because in fact the most successful pop songs (measured in terms of economic success) prove the point anyway, with their relentless repetition--reiteration--of melodic lines and rhythmic figures, a practice justified in order to make a song "suitable for dancing".

Lester Bangs cited “Leader of the Pack” by the Shangri-Las as a positive example of a song with hooks, while Kim Carnes’ “Bette Davis Eyes” is a negative example (an instance of music business "cynicism"). I might cite “My Guy” by Mary Wells as a positive example, or The Temptations' "Just My Imagination (Running Away With Me)," the type of song that if I hear it early in the day I hear it the rest of the day (in a good way). But if Bachman-Turner Overdrive’s “Takin’ Care of Business” comes on the radio, the radio goes off--as fast as my synapses can fire.

For further reading:

Lick

Riff

Theme

Melody

Ostinato

Saturday, May 17, 2008

The Mad Man

Will Elder (1921-2008), among the first cartoonists whose work appeared in that long-running magazine satirizing American popular culture, Mad, at its inception in 1952, has died at age 86 of Parkinson’s disease. Among Elder's other creations for the venerable magazine was the figure of the career criminal named "Mole" who was always tunneling into disaster. And in issue #27 (April 1956) the magazine offered for mail-in purchase a 5x7 black & white portrait of the “What, Me Worry?” kid, first drawn by Elder. He thus was the first artist to draw that magazine's iconic kid with the huge grin, although a couple of issues later (#30), artist Norman Mingo drew a color rendition, and "Alfred E. Neuman" was born. The original black & white portrait by Elder is now a valuable collector’s item, as it was offered for sale only in a couple of issues before Mingo's version replaced it.

Will Elder (1921-2008), among the first cartoonists whose work appeared in that long-running magazine satirizing American popular culture, Mad, at its inception in 1952, has died at age 86 of Parkinson’s disease. Among Elder's other creations for the venerable magazine was the figure of the career criminal named "Mole" who was always tunneling into disaster. And in issue #27 (April 1956) the magazine offered for mail-in purchase a 5x7 black & white portrait of the “What, Me Worry?” kid, first drawn by Elder. He thus was the first artist to draw that magazine's iconic kid with the huge grin, although a couple of issues later (#30), artist Norman Mingo drew a color rendition, and "Alfred E. Neuman" was born. The original black & white portrait by Elder is now a valuable collector’s item, as it was offered for sale only in a couple of issues before Mingo's version replaced it.

An obituary can be found here, and an interesting interview over here. Daniel Clowes’ book, Will Elder: The Mad Playboy of Art, is widely available on the web, as is Elder's Chicken Fat, a collection of drawings, sketches, and cartoons. Among Elder's other famous creations is "Little Annie Fanny," the comic strip featuring a buxom blond that appeared in Playboy magazine; collections of these 'toons are also available in book form.

I suspect that rather than mourn his passing, Elder would prefer us to inject some humor into our day today--inject some humor "in a jugular vein."

Friday, May 16, 2008

Lumpy Pandemonium Ballet

At the beginning of this year I embarked on a peculiar, perhaps grossly self-indulgent experiment of trying to listen to all the rock and R&B albums released in the year of 1968--forty years ago--in the order, as best as I could determine, in which they were released. Why 1968? Because it was the year I seriously began to collect albums. I cannot claim that the following list of albums is exhaustive; rather, it consists of those albums I either had or I could easily get my hands on (eBay therefore came in handy on occasion). As might be expected, the experiment prompted me to fill in some gaps in my collection. I sat down over my Christmas break and compiled as comprehensive a list as I could make, then determined which albums I already owned (on vinyl LP or compact disc) and which I would need to acquire. As it turns out, I had a good number of them, although I purchased a few on CD because I wanted the liner notes and bonus tracks.

At the beginning of this year I embarked on a peculiar, perhaps grossly self-indulgent experiment of trying to listen to all the rock and R&B albums released in the year of 1968--forty years ago--in the order, as best as I could determine, in which they were released. Why 1968? Because it was the year I seriously began to collect albums. I cannot claim that the following list of albums is exhaustive; rather, it consists of those albums I either had or I could easily get my hands on (eBay therefore came in handy on occasion). As might be expected, the experiment prompted me to fill in some gaps in my collection. I sat down over my Christmas break and compiled as comprehensive a list as I could make, then determined which albums I already owned (on vinyl LP or compact disc) and which I would need to acquire. As it turns out, I had a good number of them, although I purchased a few on CD because I wanted the liner notes and bonus tracks.

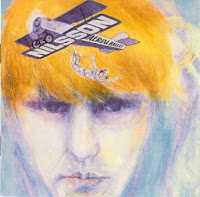

I must emphasize that this list is rather idiosyncratic, neither a "classic rock" list nor an attempt to listen to every pop album released that year. What follows is the order in which I have listened to the albums (with one exception, as indicated). This week, for instance, I have been listening to Frank Zappa's album Lumpy Gravy, which so far as I was able to determine, was released on LP on May 13, 1968--forty years ago this week. Next week I'll listen to Spooky Tooth's It's All About. Predictably, during the course of compiling this list I found that my memory was faulty: I mistakenly had albums released later in the year in the record bins earlier in the year (and vice versa). Happily, I must also admit to having discovered a few albums I'd overlooked all those years ago that have now become my favorites--Harry Nilsson's Aerial Ballet, for instance. In fact, I liked it so much I was motivated to acquire his previous album, Pandemonium Shadow Show (1967), which I learned was one of John Lennon's favorites and which has become, four decades late(r), one of mine. While I'd always very much liked Nilsson, I was most familiar with his later albums; I am delighted to have finally given these albums the careful listen they so richly deserve.

If any readers have the inclination to correct the information below, or suggest I acquire titles that I've so far overlooked, please don't hesitate to contact me. I'll periodically update the list and correct it, and of course add to it in future blogs. At the end of the month, if I remember, I'll post my June listening schedule. Consider it the aural equivalent of what book stores call a summer reading program. If there is a certain "classic" album missing from the following list, then you can be reasonably certain that it wasn't yet released by the end of May 1968 (e. g., Pink Floyd's A Saucerful of Secrets, released in June, or The Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo, released in July).

Please note that some live albums, released two or three years after their original recording (or in some cases, decades later), have been reinserted into the proper sequence to reflect the time they were recorded. These titles are indicated in brackets [ ] after the group's name. Dates reflect US release unless indicated otherwise. Finally, some release dates were determined by the album's catalog number, admittedly not the best way to determine the release date, but a reasonably good indicator nonetheless.

January

Elvis Presley, Elvis’ Gold Records, Volume 4 - 1/2

The Byrds, The Notorious Byrd Brothers- 1/3

The Kinks, Live at Kelvin Hall - 1/12

The Bee Gees, Horizontal

Autosalvage, Autosalvage

Blue Cheer, Vincebus Eruptum

Steppenwolf, Steppenwolf

The Electric Prunes, Mass in F Minor

Canned Heat, Boogie with Canned Heat - 1/21

Aretha Franklin, Lady Soul - 1/22

Spirit, Spirit - 1/22

Van Dyke Parks, Song Cycle - 1/29

February

Mason Williams, The Mason Williams Phonograph Record

Blood, Sweat & Tears, Child is Father to the Man

Dr. John the Night Tripper, Gris-gris

Iron Butterfly, Heavy

Tomorrow, Tomorrow

Graham Gouldman, The Graham Gouldman Thing

The Rascals, Once Upon a Dream - 2/19

Otis Redding, The Dock of the Bay - 2/23

Fleetwood Mac, Fleetwood Mac - 2/24

March

Laura Nyro, Eli and the Thirteenth Confession - 3/3

The United States of America, The United States of America - 3/6

The Mothers of Invention, We're Only In It For the Money

Vanilla Fudge, The Beat Goes On

Cream, [Live Cream] [4/70]

The Move, Move [listened to out-of-sequence, just recently]

The Electric Flag, A Long Time Comin’

Joni Mitchell, Song For a Seagull

Incredible String Band, The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter

The Association, Birthday

The Yardbirds, [Live Yardbirds: Featuring Jimmy Page] - 3/30 [5/71]

April

Simon & Garfunkel, Bookends - 4/3

Moby Grape, Wow/Grape Jam - 4/3

The Zombies, Odessey & Oracle - 4/9 [UK date]

Janis Joplin w/ Big Brother and the Holding Company, [Live at the Winterland ’68, 4/12-13] [1998]

Jimi Hendrix Experience, Smash Hits [UK date]

The Rose Garden, The Rose Garden

Scott Walker, Scott 2

The Monkees, The Birds, The Bees & The Monkees - 4/22

Stephen Stills, [Just Roll Tape, 4/26] [2007]

Sly & The Family Stone, Dance to the Music - 4/27

Scott Walker, Scott 2 - 4/27

The Mamas & Papas, The Papas & The Mamas - 4/29

May

Jefferson Airplane, [Live at the Fillmore East, 5/3-4] [1998]

The Collectors, The Collectors

Quicksilver Messenger Service, Quicksilver Messenger Service

Frank Zappa, Lumpy Gravy - 5/13

Spooky Tooth, It’s All About

The Small Faces, Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake - 5/24

Max Frost And The Troopers, Shape of Things to Come 5/29

[Faux band from AIP’s Wild in the Streets, released 5/29/68]

Again, corrections and/or emendations are welcome (please provide source of your information if you find my dating faulty). I'll try to post June's listening schedule before the end of the month.

List emended 8 September 2008

Thursday, May 15, 2008

Bozo Dionysus

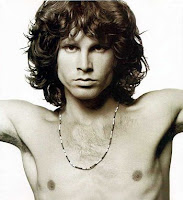

For what perverse reason do “classic rock” radio stations always play the Doors’ “Riders on the Storm” whenever it’s raining? I awoke to find it raining here this morning, and sure enough, as I sat down to check my email after having turned on the radio, like clockwork the DJ played “Riders on the Storm.” The song is instantly recognizable, of course: the opening crash of thunder, the tinkling of the keyboard imitating falling raindrops, and, inevitably, the sinister lyric about the “killer on the road” whose “brain is squirmin’ like a toad.” As poetry it is of a badness not to be believed; there is no group in rock history that so insistently challenges the issue of whether musical quality and canonical status go hand in hand as do the Doors.

For what perverse reason do “classic rock” radio stations always play the Doors’ “Riders on the Storm” whenever it’s raining? I awoke to find it raining here this morning, and sure enough, as I sat down to check my email after having turned on the radio, like clockwork the DJ played “Riders on the Storm.” The song is instantly recognizable, of course: the opening crash of thunder, the tinkling of the keyboard imitating falling raindrops, and, inevitably, the sinister lyric about the “killer on the road” whose “brain is squirmin’ like a toad.” As poetry it is of a badness not to be believed; there is no group in rock history that so insistently challenges the issue of whether musical quality and canonical status go hand in hand as do the Doors.

I can think of no other band of the so-called “classic rock” era so inevitable, and so dubious, as the Doors. Neither could the incomparable Lester Bangs, certainly the wittiest and most iconoclastic of American rock critics. His temperament was such that he couldn’t tolerate the solecism of the rock star, and if ever there were the sort of rock star who excelled at impropriety and obnoxiousness, it was Jim Morrison, characterized by Bangs in an essay published in 1981 as “Bozo Dionysus.” Bangs’ essay, “Jim Morrison: Bozo Dionysus a Decade Later,” was written in response to his having read Jerry Hopkins’ and Danny Sugerman’s Morrison biography, No One Here Gets Out Alive. Having read the book, Bangs concluded that Morrison “was apparently a nigh compleat asshole from the instant he popped out of the womb until he died in the bathtub in Paris....,” as illustrated by incidents such as when he was a kid rubbing dog shit in his little brother’s face, or his later, pathetic, “cock-flashing incident” in Miami in 1969, an action, Bangs observed, that was motivated out of “the same desperation that drives millions of far less celebrated alcoholics.”

What makes the Doors so inevitable as rain? Although he was writing early in 1981 in the context of a Doors resurgence (repeated a decade later with the release of Oliver Stone’s film), I think Lester Bangs is correct when he observes:

... can you imagine being a teenager in the 1980s and having absolutely no culture you could call your own? Because that’s what it finally comes down to, that and the further point which might as well be admitted, that you can deny it all you want but almost none of the groups that have been offered to the public the past few years begin to compare with the best from the Sixties. And this is not just Sixties nostalgia—it’s a simple matter of listening to them side by side and noting the relative lack of passion, expansiveness, and commitment in even the best of today’s groups. (Main Lines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste: A Lester Bangs Reader, p. 215)

Bangs has a point, and I can provide anecdotal evidence to substantiate it. Several semesters after I started teaching college twenty-seven years ago, I had a student in my class who had the distinction of having been born at the Woodstock festival in 1969—there were two babies born at Woodstock, and he was one of them. (Not that it meant anything to him. His stepfather told me this, not the kid—at the time—to whom I’m referring.) He was a punk rocker with an aggressive, “fuck you” attitude—died hair, safety pins in the ears, the whole apparatus. He dressed like a Hell’s Angel—motorcycle boots, leather pants and jacket, always a black T-shirt with an image or writing on it. The overall effect was comic, however, because of his age—because he was so young, he was a sort of ludicrous pastiche of a Hell’s Angel, especially when he wore a bandanna, and became a sort of Kewpie doll version of a Hell's Angel. He liked to hang out but didn’t have very much money, so he used to get the owner of the record store to play albums for him, and he would pass judgment based on only a couple of listens. He liked the Sex Pistols and the early Clash, and he liked American groups such as The Ramones and Black Flag. Most importantly, he loved Iggy Pop. He didn’t like later Clash albums such as Sandinista! (1980), because while he claimed to be apolitical, he was actually conservative; he didn’t like the Left-leaning, liberal posturing of that album. And he despised Combat Rock (1982), saying the Clash were sell-outs.

He had very little to say about Sixties groups (with the exception of The Stooges, of course), but he did, though, express great love for the music of the Doors. If you stop to think about it, he was growing in his mother’s womb when Jim Morrison drunkenly flashed his flaccid cock on stage in Miami in March 1969; he wasn’t yet two years old when Morrison died. He would have been around eleven years old when Hopkins’ and Sugerman’s Morrison biography was published and became a best-seller. And he would have been twenty-one when Oliver Stone’s The Doors was released, and I’m very sure the depiction of Jim Morrison in that film made a huge impression on him, as it did others of his generation.

Can you imagine being a teenager in the 1980s and having absolutely no culture you could call your own? Lester Bangs asked, rhetorically, and it was absolutely the right question to ask in order to explain why the Doors had a resurgence beginning in the 1980s. To answer the question is to understand why Iggy Pop is so beloved by that same generation of teenagers. “Surely he [Morrison] was one father of New Wave, as transmitted through Iggy and Patti Smith,” Bangs observed, although he goes on to say, “but they have proven to be in greater or lesser degree Bozos themselves” (219).

Why the appellation “Bozo Dionysus”? I think what Bangs is getting at is the disjunction between what Morrison sought to do and what he actually did: “Jim Morrison had not set out, initially, to be a clown,” but that’s what he became when his literary ambitions were frustrated. By the time of infamous flashing event in Miami, he was too drunk on stage to do anything but do something pathetic, which he, sure as rain, did. He had become redundant by the time L. A. Woman was released in 1971 (for some, however, he had nothing left to say after the Doors’ first album) and like many failed poets, found solace in booze. Perhaps he sought to find a literary renewal in Paris, but all he found was more drugs and, inevitably, alcohol.

The irony is that the song for which the Doors perhaps are most famous, “Light My Fire,” was written not by Morrison but by Robby Krieger (unless you count the lyrics, of course), but I think Lester Bangs is right when he claims that the one great song Morrison had in him was “People Are Strange”:

People are strange when you’re a stranger

Faces look ugly when you’re alone

Women seem wicked when you’re unwanted

Streets are uneven when you’re down

The song’s evoking of a subjective disorientation and dislocation was the effect Morrison frequently sought, but seldom achieved; the song happens to be on what seems to me to be the best, as in listenable, Doors album, Strange Days (1967). Later albums, such as The Soft Parade (1969), fail, primarily because the band was by then engaged in self-parody, and no one can do parody any better than the artist does of himself: think of the “When I was back there in seminary school” and “You cannot petition the Lord with prayer!” rant that begins the muddled “The Soft Parade”—self-parody at its best, and therefore an embarrassment for the listener.

I again refer to Lester Bangs, who claimed that, like it or not, Jim Morrison was one of the fathers of contemporary rock. In Lacanian, that is, psychoanalytic terms, his claim can be understood as saying that Morrison's function is that of the objet petit a, the lure around which the drive circulates, the absence around which the rock community explains its history to itself. In other words, if Jim Morrison didn't exist, we would have to invent him.

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

Robert Rauschenberg, 1925-2008: Artist of the Abject

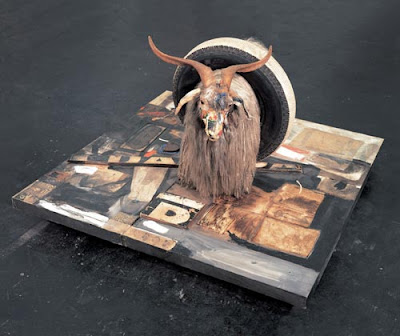

Although his work is derided by many critics, Robert Rauschenberg, who died this past Monday, May 12 at the age of 82, eventually may become known as one of the most important American artists of the twentieth century. Primarily known for his “combines”— combinations of three-dimensional objects and paint—for me, Rauschenberg is best remembered as an artist of the abject. Abject commonly means “excessively humble,” or sometimes “contemptible,” but in this case I'm also using "abject" to refer to common, everyday waste, thrown away quotidian objects, “cast offs”—in short, “refuse.”

Perhaps his most famous work is Monogram (pictured), depicting a stuffed Angora goat standing atop a platform consisting of a collaged painting and amid objects such as a police barrier, a shoe heel, and a tennis ball. Oddly, the goat has a used automobile tire wrapped around the middle of its body. I read where Rauschenberg, raised as a Christian fundamentalist in Port Arthur, Texas, said as a child he suffered a severe emotional trauma as a result of his father killing his pet goat for food. He no doubt loved that goat, and in some sense, consciously or unconsciously, modeled his own creative method after a goat’s behavior, for after all, a goat finds everything, even the most banal refuse, interesting—and potentially edible. Rauschenberg said he would roam the streets near his studio in New York for things that he would subsequently incorporate into his art. We can therefore conceive of his entire creative output—and I mean this very seriously—as inspired by the relentlessly foraging behavior of that old, beloved goat. A goat is eclectic in its tastes; it finds everything equally interesting, even the most abject of objects.

I should mention that critic Robert Hughes finds Monogram to have an entirely different meaning, the title itself serving as a statement of personal identity. Hughes observes:

... the wonderful Monogram, the stuffed Angora goat Rauschenberg found in an office supply store on 23rd Street in the early 1950s and encircled with a car tyre. One looks at it remembering that the goat is an archetypal symbol of lust, so Monogram is the most powerful image of anal intercourse ever to emerge from the rank psychological depths of modern art. Yet it is innocent, too, and sweet, and (with its cascading ringlets) weirdly dandified: a hippy goat, a few years before the 1960s. Fifty years after its creation, it remains one of the great, complex emblems of modernity, as unforgettable (in its way) as the flank of Cézanne’s mountain, the cubist kitchen table or the wailing woman in Guernica.

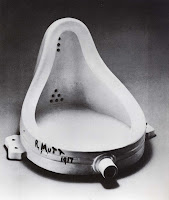

While it is true that the goat is a conventional phallic symbol, it is also true that by the late 1950s, when Monogram was being created (1955-59), the most potent symbol of America—this at a time before Lady Bird Johnson’s “Beautify America” campaign a few years later—was a car tire. Used car tires were ubiquitous common objects that proliferated everywhere, like Wallace Stevens’ jars; there were, literally, mountains of them all around the country. While Hughes may well be correct in his interpretation of the meaning of Monogram, I should say that, in contrast to Hughes, for me the most famous emblem of modernity, and one of the most influential works of the twentieth century, is Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain—an inverted urinal.  Rauschenberg’s artistic works have frequently been characterized as blurring the line between art and modern life, and there is no more common emblem of modern life, as Jacques Lacan observed, than the public toilet. Hence Rauschenberg might well have understood that the definitive art work of the twentieth-century was a toilet—that is to say, an abject object.

Rauschenberg’s artistic works have frequently been characterized as blurring the line between art and modern life, and there is no more common emblem of modern life, as Jacques Lacan observed, than the public toilet. Hence Rauschenberg might well have understood that the definitive art work of the twentieth-century was a toilet—that is to say, an abject object.

So if, by chance, someday you hear the work of Rauschenberg being scorned, or perhaps the derisive observation that it impossible to determine whether his works belong in a thrift shop or an art museum, just think of the insatiable foraging activity of that miserable goat--who loved all things abject--killed for food, whose behavior became the inventive model for one of the more important artists--certainly the least pretentious--of the twentieth century.