Yesterday's blog entry on late guitarist Jerry Cole prompted me to revisit the issue of the popularization of psychedelic music. I say psychedelic music because to be perfectly accurate I think the word "psychedelia" names a larger movement than simply a musical one, that is, "psychedelia" would refer to trends not only in music but in the popular arts (such as poster-making), live concert performance (synaethesia), and so on. Since posting yesterday's blog, my thoughts have been preoccupied not only with how we have gone about defining psychedelic music but with how and in what way it came to be recognized as a distinctive kind of (serious) music in the first place. I've come to the conclusion that our own desires have much to do in forming the musical form we have come to call "psychedelic."

Yesterday's blog entry on late guitarist Jerry Cole prompted me to revisit the issue of the popularization of psychedelic music. I say psychedelic music because to be perfectly accurate I think the word "psychedelia" names a larger movement than simply a musical one, that is, "psychedelia" would refer to trends not only in music but in the popular arts (such as poster-making), live concert performance (synaethesia), and so on. Since posting yesterday's blog, my thoughts have been preoccupied not only with how we have gone about defining psychedelic music but with how and in what way it came to be recognized as a distinctive kind of (serious) music in the first place. I've come to the conclusion that our own desires have much to do in forming the musical form we have come to call "psychedelic."

I raise these questions because in yesterday's blog I mentioned that Jerry Cole's MySpace page indicates that the musician was "an architect of psychedelia," citing his "proto-psych albums" The Inner Sounds of the Id and The Animated Egg as indications of his contributions to the popularization of this form of music. But the more I have thought about it, the less satisfied I am with this claim, not because I wish to diminish his contributions to popular music, but because to my knowledge these albums were not recognized as seminal contributions at the time of their release. The problem is that we tend to piece together a history comprised of figures and works which largely reflect our own desires--and little else. Numerous websites exist extolling the virtues of rock albums--perhaps unfairly--that have been neglected in popular musical history, but we should remind ourselves that when we write our own history as a "corrective," we do not resurrect a "pure" past, but a past composed of imperfect memories, both on an individual level and on a collective level. Rewriting history to fit our own desires does not, alas, correct what is already an imperfectly written history.

Surely there must be something more distinctive and more singular about what we call "psychedelic music" than the kinds of sounds resulting from "non-linear amplification," meaning that the sounds that come out of the speaker are not the sounds that go in. I'd suggested that Jerry Cole represented an important link between the West Coast surf/hot rod "reverb" guitar and the distorted (“fuzz”) guitar characteristic of early psychedelic music, but surely, I thought, there must be more to it than the role of the guitar. Obviously, developments in non-linear amplification contributed to the development of psychedelic music--the Leslie speaker and the ring modulator being examples of such technology--but there has to be more to its invention in the 1960s than the role of technology. Personally, I often find it hard to distinguish between what some enthusiasts name "garage band" music and what some name "psychedelic"; if "garage" and "psychedelic" both refer to a sort of recording engineered in a particular fashion, containing lots of guitar feedback, fuzz tones, and reverb, then we're inexorably entangled in a daunting language game in which our words are, literally, meaningless.

It also occurred to me that psychedelic music itself was not immediately accepted (as in, "became popular overnight"); the audience for it had to be developed. Despite the great reverence we have for the music now--and the high prices some of these "historic" albums now fetch on eBay and elsewhere--early instances of so-called psychedelic music failed, largely explaining why so much early psychedelic music can only be found on obscure 45s, issued by independent labels, and budget LPs issued by Crown, Custom, and Alshire, to name a few such labels. In the 1960s, just as now, the major labels were only interested in the sort of product that adhered to the wall--the economics driving this procedure being to throw a lot of stuff at the wall and see what sticks, then package and sell the kind that sticks--and, frankly, very few early albums putatively containing psychedelic music sold very well at all. Why else are they now so hard to find and why else were they issued on minor or budget labels?

According to wikipedia.org (by no means definitive), the first use of the word "psychedelic" in popular music was on the Holy Modal Rounders' single "Hesitation Blues" (1964), hardly a best seller. The harsh fact is, if it weren't for the soundtrack to Easy Rider (1969), the music of the Holy Modal Rounders would never have been known beyond a small coterie of enthusiasts and musicologists and students of the arcane. Of course, simply because the word "psychedelic" is used in a piece of music doesn't make the music itself "psychedelic," which is certainly the case with this song. I strongly suspect that Stampfel and Weber encountered the word as a result of the publication, earlier that year, of Timothy Leary's, Ralph Metzner's, and Richard Alpert's book, The Psychedelic Experience (New Hyde Park: University Press, 1964); whether they took its insights seriously is beside the point. A couple of years later, in 1966, excerpts from Leary et al.'s The Psychedelic Experience were issued on LP as a spoken word album by Folkways/Broadside Records (album cover pictured), which I suspect was the first use of the word "psychedelic" on an LP record. Although it is of trivial significance, the first use of the word "psychedelic" on a rock/pop record was probably on the Deep's Psychedelic Moods, apparently issued in October 1966 (according the CD re-issue's liner notes) on Cameo-Parkway, just a week or two before the Blues Magoos' Psychedelic Lollipop (Mercury), and about a month before the 13th Floor Elevators' The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators (International Artists). Mercury is perhaps the only "major" label represented here.

Gregory L. Ulmer has observed that any form of unconventional or radically new knowledge is at first perceived to be a bad joke--Freud's theory of psychoanalysis, for instance, and Darwin's theory of human beings evolving from monkeys were, in fact, both considered bad jokes. It is clear that popular music's initial appropriation of Leary et al.'s drug-enabled psychedelic experience--somewhat derisively referred to as "mind-expanding"--took the idea of a "psychedelic experience" as a joke: the deliberate mis-pronunciation of the word psychedelic as "psycho-delic" in "Hesitation Blues," for instance, or as evidenced by the titling of the Blues Magoos album as "Psychedelic Lollipop." Even referring to music as psychedelic (as in "psychedelic sounds") is a joke. Likewise, the records didn't sell well because they, too, were perceived as jokes. Indeed, the idea of the joke permeates early albums claiming to be psychedelic, for instance, Friar Tuck and His Psychedelic Guitar (1967), The Animated Egg (1967), Hal Blaine's Psychedelic Percussion (1967), and so on.

It is clear that there are widespread misperceptions about what is often called "psychedelic music": how it was initially perceived, both by its audience and its practitioners, and about its subsequent influence. I find it strange that the psychedelic era is now popularly associated with San Francisco, even though the Deep's Psychedelic Moods was recorded in Philadelphia (and its brainchild, Rusty Evans--a pseudonym for artist Marcus Uzilevsky--was from New York), the Blues Magoos were from the Bronx, and the 13th Floor Elevators were from Texas. Moreover, I wonder if a majority of the members of the so-called "counterculture" ever perceived Timothy Leary as anything but a joke. I'm reasonably certain that "psychedelic," as a term used to described a certain type of rock music, had no credibility in 1967; in fact, at the time it was probably only used pejoratively. The word probably did not have any positive connotations in 1968 or 1969, either. Was it ever used positively at the time? Certainly not until it began to be used as a term through which individuals expressed their own desires, and began to identify themselves with the music and the culture surrounding it. In previous entries I've argued that what is called "Bubblegum" music emerged out of psychedelic music, and I think this is correct, but one has to remember that "Bubblegum" was not a term invented by those who liked and listened to the music, but those who disliked, and perhaps even despised it.

Tuesday, June 10, 2008

Psychedelic Psounds

Monday, June 9, 2008

Space-Age Surf Guitar And Hot Rod Inner Id Music

Jerry Cole (born Jerry Coletta in 1939), the so-called “King of the Hot Rod Guitar” and allegedly one of most frequently recorded session guitarists in American popular music, died on Wednesday, June 4 at his home in Corona, California, at age 68. In the Sixties Cole was a highly sought-after session player, lending his talents to records by the Byrds (“Mr. Tambourine Man”), Nancy Sinatra (“Boots”), the Beach Boys (Pet Sounds; one of the Leslie'd guitars on the instrumental "Pet Sounds" track was Cole's) and Paul Revere & the Raiders (“Kicks”) among others. With his own group, the Spacemen, Cole released four albums of “space-age surf music” beginning with Outer Limits (1963). More often, though, Jerry Cole was an anonymous member of a faux band, playing on numerous hot rod, drag strip, surf, go-go, rockabilly, and psychedelic albums for Capitol and Liberty but more often for budget labels such as Crown, Cornet, Custom, and Alshire. I did a rather quick web search and apparently all of the following one-offs were either Jerry Cole using a pseudonym or Jerry Cole as a member of the band. Many of these records are instrumental albums, dating 1960-67.

The Scramblers, Cycle Psychos

Billy Boyd, Twangy Guitars

The Blasters, Sounds of the Drag

Eddy Wayne, The Ping Pong Sound of Guitars in Percussion

The Winners, Checkered Flag

The Hot Rodders, Big Hot Rod

The Deuce Coupes, The Shutdowns

Mike Adams and the Red Jackets, Surfers Beat

The Id, The Inner Sounds of the Id (RCA)

The Animated Egg

The Mustang, Organ Freakout! (apparently Jerry Cole and the Id backing keyboardist Paul Griffin aka “The Mustang”)

Cole’s Myspace page avers that he “was an architect of psychedelia with his proto-psych albums The Id and The Animated Egg." If so, he represents an important link between the West Coast surf/hot rod "reverb" guitar and the distorted (“fuzz”) guitar so characteristic of early psychedelia. According to the Acid Archives at lysergia.com, Jerry Cole indicated that "the original tracks [used on The Animated Egg] were laid down during sessions for the Id Inner Sounds LP on RCA in 1966, then later sold to Alshire." Collectors and musicologists have identified these tracks, and others from the same sessions, as appearing on several LPs credited to different artists: Young Sound '68; 101 Strings, Astro-Sounds From Beyond the Year 2000; Bebe Bardon & 101 Strings, The Sounds of Love; The Haircuts and The Impossibles, Call it Soul; Black Diamonds, A Tribute to Jimi Hendrix [re-titled Animated Egg album with songs re-titled in order to invoke Hendrix song titles]; The Generation Gap, Up Up and Away; The Projection Company, Give Me Some Loving; and other budget label LPs. One critic referred to these tracks as "B movie trash psych with fuzz, reverb, and cheesy go-go organ." If you're interested, “Ah Cid" (get it?) from The Animated Egg can be found here.

Sundazed has re-issued on CD the albums by Jerry Cole and the Spacemen, but according to Cole's Myspace page, Sundazed also plans to re-issue The Animated Egg, Astro-Sounds From Beyond the Year 2000, The Inner Sounds of the Id, and other recordings.

Thursday, June 5, 2008

Memory and Forgetting

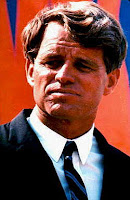

Forty years ago today was one of those days that I remember all too well. In the early morning of Wednesday, 5 June 1968, Robert F. Kennedy was shot by an assassin shortly after finishing the victory speech he gave upon winning the California Democratic Presidential primary. He survived the day, but would die the next, on June 6. I say I remember the day (bits and pieces), although I don't remember the moment itself. The funny thing is, I remember watching the news report about his primary victory and privately celebrating it, but in those days television stations signed off at midnight, and hence I'd gone to bed a couple hours before the shooting happened (Central Time). At the time, my parents owned a business, a bowling alley, and normally they weren't able to close much before 1 or 2 a.m.--very late. I remember my father waking me up when he and my mother arrived home after closing the place, and told me the terrible news (apparently hearing about it on the radio). Although it was highly unlikely that my father would have voted for Robert Kennedy--he was a "staunch" Republican--I think he and my mother (who probably would have voted for RFK) were both very upset by the event. The memory of John F. Kennedy's assassination was not all that far distant in the past, and two months earlier, of course, Martin Luther King, Jr. had been assassinated; although King's and Kennedy's assassinations were two months apart, my memory has collapsed the time between them into contiguous events, one right after the other.

Forty years ago today was one of those days that I remember all too well. In the early morning of Wednesday, 5 June 1968, Robert F. Kennedy was shot by an assassin shortly after finishing the victory speech he gave upon winning the California Democratic Presidential primary. He survived the day, but would die the next, on June 6. I say I remember the day (bits and pieces), although I don't remember the moment itself. The funny thing is, I remember watching the news report about his primary victory and privately celebrating it, but in those days television stations signed off at midnight, and hence I'd gone to bed a couple hours before the shooting happened (Central Time). At the time, my parents owned a business, a bowling alley, and normally they weren't able to close much before 1 or 2 a.m.--very late. I remember my father waking me up when he and my mother arrived home after closing the place, and told me the terrible news (apparently hearing about it on the radio). Although it was highly unlikely that my father would have voted for Robert Kennedy--he was a "staunch" Republican--I think he and my mother (who probably would have voted for RFK) were both very upset by the event. The memory of John F. Kennedy's assassination was not all that far distant in the past, and two months earlier, of course, Martin Luther King, Jr. had been assassinated; although King's and Kennedy's assassinations were two months apart, my memory has collapsed the time between them into contiguous events, one right after the other.

I was just a teenager at the time, but I remember the summer of 1968 being a terrible one--the Democratic Convention in Chicago, likewise a disaster, was just two months away. For reasons I no longer remember, Robert Kennedy was a very powerful figure for me (the figure of the martyred JFK perhaps a reason, but certainly not the only one), and hence I cannot explain the reason for it, but I do remember how badly I took the news of RFK's death. I remember the day after he died, I was sitting by myself at the front counter of the bowling alley--it was open for business, but there wasn't a soul in the place except for me--and sobbing over the news of his death. Again, I can't tell you precisely why. I no longer remember. Youth, naïvete, the historical moment, the power of the media.

The location of his assassination, the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, is now gone, and with it, of course, the pantry off the Embassy Room, where the actual shooting took place. The Ambassador Hotel opened in 1921, designed by renowned architect Myron Hunt, who also designed the Rose Bowl Stadium, among other famous buildings in L.A. Located at 3400 Wilshire Boulevard, it was about four miles south and east of Sunset and Vine in Hollywood. Six Academy Award ceremonies were held there--including the ceremony the year Gone with the Wind swept the Awards. The Hotel’s Cocoanut Grove became famous for live entertainment on the West Coast for decades. Amid controversy, the Ambassador Hotel was pulled down in 2006.

One can't imagine the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas being pulled down, but then Robert F. Kennedy, despite his popularity at the time, hasn't captured the public memory like John F. Kennedy. The location of one assassination is memorialized--become part of the official cultural memory, while the location of the other has been erased. These disparities reveal the writing of history itself, which is always both an act of remembering, and forgetting.

Wednesday, June 4, 2008

Gunslingers and Guitarschlongers

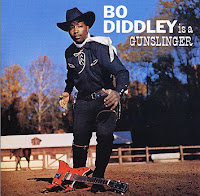

Last time I wrote about the significance of the album cover to Bo Diddley's Bo Diddley is a Gunslinger (Checker, 1960; pictured in the blog entry below). I observed that Bo Diddley wasn’t the first black musician to appropriate the iconography of the American West for an album cover; as Michael Jarrett has pointed out, jazz great Sonny Rollins did that, with Way Out West (Contemporary, 1957). Subsequently, the association of the popular musician with the myths of the American West--in particular, the musician as outlaw hero--became a significant one in the 1960s. I suggested that by appropriating the image of the outlaw hero for a generation of rock ‘n’ roll musicians, Bo Diddley became an iconic figure of rock 'n' roll, not simply a musical inspiration. Bo Diddley's album was released at the beginning of the 1960s. During the decade of the 60s, through a process that Robert Christgau calls a "barstool-macho equation of gunslinger and guitarschlonger," the musician as outlaw was formed, and his image, formerly associated with the values of the bohemian subculture, became, according to Michael Jarrett, "an icon recognized by all and embraced by many" (200). According to Robert Ray, the musician as outlaw stood for "freedom from restraint, a preference for intuition as the source of conduct, a distrust of the law, bureaucracies, and urban life" (255).

Last time I wrote about the significance of the album cover to Bo Diddley's Bo Diddley is a Gunslinger (Checker, 1960; pictured in the blog entry below). I observed that Bo Diddley wasn’t the first black musician to appropriate the iconography of the American West for an album cover; as Michael Jarrett has pointed out, jazz great Sonny Rollins did that, with Way Out West (Contemporary, 1957). Subsequently, the association of the popular musician with the myths of the American West--in particular, the musician as outlaw hero--became a significant one in the 1960s. I suggested that by appropriating the image of the outlaw hero for a generation of rock ‘n’ roll musicians, Bo Diddley became an iconic figure of rock 'n' roll, not simply a musical inspiration. Bo Diddley's album was released at the beginning of the 1960s. During the decade of the 60s, through a process that Robert Christgau calls a "barstool-macho equation of gunslinger and guitarschlonger," the musician as outlaw was formed, and his image, formerly associated with the values of the bohemian subculture, became, according to Michael Jarrett, "an icon recognized by all and embraced by many" (200). According to Robert Ray, the musician as outlaw stood for "freedom from restraint, a preference for intuition as the source of conduct, a distrust of the law, bureaucracies, and urban life" (255).

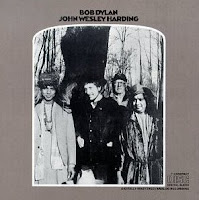

Outlaw iconography became a metaphor for individuality, integrity, and self-reliance. In addition  to albums such as The Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968) and the Eagles' Desperado (1972) that I mentioned last time, we can also add the following albums and songs. Perhaps a key album in the development of the popular musician as outlaw hero was Bob Dylan's John Wesley Harding (1967), in which he merged his own biographical details with the figure of the notorious Texas outlaw. Hence Jimi Hendrix's decision to cover "All Along the Watchtower" is much more deliberate than it at first may seem. The following list of albums with frontier imagery is not intended to be an exhaustive list, merely an indication of how widespread was the appropriation of the imagery of the American West.

to albums such as The Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968) and the Eagles' Desperado (1972) that I mentioned last time, we can also add the following albums and songs. Perhaps a key album in the development of the popular musician as outlaw hero was Bob Dylan's John Wesley Harding (1967), in which he merged his own biographical details with the figure of the notorious Texas outlaw. Hence Jimi Hendrix's decision to cover "All Along the Watchtower" is much more deliberate than it at first may seem. The following list of albums with frontier imagery is not intended to be an exhaustive list, merely an indication of how widespread was the appropriation of the imagery of the American West.

Duane Eddy - Have 'Twangy' Guitar, Will Travel (1958)

Bo Diddley - Have Guitar, Will Travel (1959)

Duane Eddy - Songs of Our Heritage (1960)

Bob Dylan - John Wesley Hardin (1967)

Quicksilver Messenger Service - Happy Trails (1968)

The Flying Burrito Brothers - The Gilded Palace of Sin (1969)

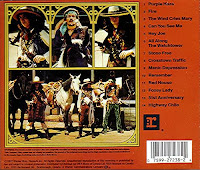

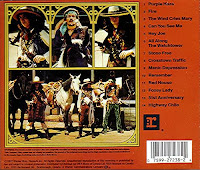

The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Smash Hits (1969) (back cover; pictured)

Mason Proffit - Wanted! Mason Proffit (1969)

The James Gang - Rides Again (1970) (and numerous other album titles)

Mason Proffit - Movin' Toward Happiness (1971)

War - The World is a Ghetto (with "The Cisco Kid") (1972)

Bob Dylan - Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973)

Willie Nelson - Red-Headed Stranger (1975)

Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Tompall Glaser, and Jessi Colter - Wanted! The Outlaws (1976)

Reggae musicians adopted the image of the outlaw hero as well: the late Jimmy Cliff with The Harder They Come (1972) and The Wailers with "I Shot the Sheriff" (1973). The so-called "Outlaw" movement in country music picked adherents as well, such as David Allan Coe, with his album Rides Again (1977). And, eventually, even a rock band from the American South named itself the Outlaws. The eponymous first album of the Outlaws was released in 1975, by which time the musician as outlaw was well over a decade old.

Monday, June 2, 2008

Bo Diddley: Outlaw Hero, 1928-2008

And so Bo Diddley, author of the so-called “Bo Diddley Beat,” one of the foundational figures in rock ‘n’ roll, is dead at age 79. There is a comprehensive obituary here, a fine appreciation by Iggy Pop (written some years ago for Rolling Stone Magazine) here, and a post-mortem tribute to Bo by Dave Alvin, once of The Blasters, here. I cannot add anything substantial to what others have astutely observed about his contributions to American popular music, but I do think that his influence on rock ‘n’ roll is more than simply musical. Although, ironically, he later became a law enforcement official, I think a great part of his allure was his image as an outlaw hero.

And so Bo Diddley, author of the so-called “Bo Diddley Beat,” one of the foundational figures in rock ‘n’ roll, is dead at age 79. There is a comprehensive obituary here, a fine appreciation by Iggy Pop (written some years ago for Rolling Stone Magazine) here, and a post-mortem tribute to Bo by Dave Alvin, once of The Blasters, here. I cannot add anything substantial to what others have astutely observed about his contributions to American popular music, but I do think that his influence on rock ‘n’ roll is more than simply musical. Although, ironically, he later became a law enforcement official, I think a great part of his allure was his image as an outlaw hero.

Pictured above is the album cover to Bo Diddley is a Gunslinger (Checker, 1960), in which Bo anticipated the black cowboy, and hired sheriff of Rock Ridge, Cleavon Little, in Blazing Saddles (1974) by some fourteen years. (The Count Basie Orchestra, incidentally, was featured in Mel Brooks' film playing jazz in the wide-open desert.) Bo Diddley wasn’t the first black musician to appropriate the iconography of the American West for an album cover—jazz great Sonny Rollins did that, with Way Out West (Contemporary, 1957)—and Herb Jeffries, who once sang with Duke Ellington’s band, had played a black cowboy in the 1930s, in Harlem on the Prairie (1937), Bronze Buckaroo (1938) and Harlem Rides the Range (1939). I choose to think that Bo Diddley saw these films as a kid, later inspiring him to conceive of this album cover.

But if the album cover of Sonny Rollins’ Way Out West, as Michael Jarrett observes, associated the jazz musician with the myths of the American West—“the musician as outlaw hero; the music as a movement or push outward” (p. 197)—Bo Diddley appropriated the image of the outlaw hero for a generation of rock ‘n’ roll musicians, and in doing so became an iconic figure of rock 'n' roll, not simply a musical inspiration. Bo Diddley's album was released at the beginning of the 1960s, and during the 1960s, notes Robert Ray, the Radical Left became obsessed with the iconography of the American frontier:

Clothes (jeans, boots, buckskins) and hairstyles (long and unkempt, moustaches) derived from daguerrotypes of nineteenth-century gunfighters; and pop music returned repeatedly to frontier images: The Buffalo Springfield's "Broken Arrow," The Grateful Dead's "Casey Jones," The Band's "Across the Great Divide," James Taylor's "Sweet Baby James," Neil Young's "Cowgirl in the Sand," Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Proud Mary," The Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo, and the Eagles' Desperado. (pp. 255-56)

His musical influence on subsequent figures such as Jimi Hendrix is widely acknowledged,  but no one has acknowledged his power as an iconic western figure, as one can see by the pictures found on the back cover of the Jimi Hendrix Experience' Smash Hits, released in 1969. While most certainly a foundational figure in rock music terms of his music, perhaps we ought to think of Bo Diddley's influence in inspiring any number of outlaw rockers as well.

but no one has acknowledged his power as an iconic western figure, as one can see by the pictures found on the back cover of the Jimi Hendrix Experience' Smash Hits, released in 1969. While most certainly a foundational figure in rock music terms of his music, perhaps we ought to think of Bo Diddley's influence in inspiring any number of outlaw rockers as well.

Sunday, June 1, 2008

Digital Divide

A few weeks ago, I wrote about my weekly (more or less) visit to the local Goodwill Store, where one can, occasionally, find something interesting. I stopped by the store yesterday, and as usual perused the record albums (why are there always so many damned gospel records?), 8-Tracks, and cassettes. The numbers of CDs are increasing (replaced by digital downloads?) but usually the CDs themselves are not in the greatest shape. I also noticed a new trend: the growing number of VHS tapes. I saw many dozens of VHS tapes, so many in fact that the managers had to construct a new bin just to handle them. I didn't find anything interesting yesterday, but that's not why I'm writing.

I also noticed four older model televisions, ranging from 13”-26”, one an old black & white, sitting next to each on a shelf, but each of the sets had a bold yellow disclaimer pasted to it stating that after February 18, 2009, the antenna would not work unless it was attached to a converter box: in other words, buy at your own risk, because come next February 18, analog signals will be turned off forever.

Seeing those old TV sets served as a reminder that in fewer than nine months, old-fashioned (analogue) broadcast television will go the way of the vinyl LP, 78s, 45s, 8-Tracks, music cassettes, VHS tapes, and so on. I suspect that many Goodwill stores around the country will find themselves inundated with old television sets within the year. It occurred to me the Goodwill store is a repository of déclassé technology—typewriters, record turntables, 8-Track players, for instance—even old DOS computers. Essentially, the function of the Goodwill Store is in part to serve as a waiting room for discarded technology, until these inert objects, perhaps, someday end up in a dusty museum or in the hands of collectors with enough disposable income to restore the things to their original glory.

Of course, the store's bins also serve to hold other discarded things as well: T-shirts emblazoned with bowl games won or lost, old toys included with Happy Meals, bestselling paperbacks with yellowing pages, gauche lamps, clunky radios, scads of coffee cups emblazoned with arcane organizations, old bed frames which once supported lovers embracing in desire. Was it Walter Pater who said he hated museums because they always inevitably gave him the impression that no one was ever young?

I read an article the other day stating that roughly 20% of U.S. households still rely on antennas to receive TV signals, which for some reason I found astonishing. And if these households don’t have sets with digital tuners, they won’t be able to pick up a digital signal--in other words, come February 18, or about nine months from now, no more television. Moreover, households with new digital TVs or special converter boxes for older sets also may need to upgrade their antennas because of a unique aspect of digital television: the signals that produce digital images can be more difficult to pick up than the old analog waves. In other words, it is quite clear that the digital transition will be more costly to people than at first anticipated. I read that the National Association of Broadcasters and the Consumer Electronics Association have a website, Antennaweb.org, that shows which stations’ signals you can get where you live and also offers help choosing an antenna. Goodwill Stores around the country better start now constructing additions, because I suspect there will be lots of TV sets showing up a few months from now. How many, instead, will show up in landfills?

Just as the Western Union Company—a company that became synonymous with the telegram—sent its last telegram in January 2006 because it could not compete with emails and cell phones, so too do the old analogue airwaves give way to digital transmission. One technology replaceth another.