In music, melisma, commonly known as "vocal runs" or simply "runs," is the technique of changing the note (pitch) of a single syllable of text while it is being sung. Music sung in this style is referred to as melismatic, as opposed to syllabic, where each syllable of text is matched to a single note. A common example of melisma, or the singing of several notes sung to one syllable of text, is the Gregorian chant. For an example of syllabic singing, think of the Beatles’ “Penny Lane”:

In music, melisma, commonly known as "vocal runs" or simply "runs," is the technique of changing the note (pitch) of a single syllable of text while it is being sung. Music sung in this style is referred to as melismatic, as opposed to syllabic, where each syllable of text is matched to a single note. A common example of melisma, or the singing of several notes sung to one syllable of text, is the Gregorian chant. For an example of syllabic singing, think of the Beatles’ “Penny Lane”:

In Penny Lane there is a barber showing photographs

Of every head he’s had the pleasure to have known

And all the people that come and go

Stop and say hello

While melismatic singing is quite common in popular music, few singers have used it, or are able to use it, tastefully. Nelson George, in The Death of Rhythm and Blues, refers to Sam Cooke (pictured) as a popular singer who effortlessly used melisma to marvelous effect:

No analysis . . . can capture the naturalness of Cooke’s sound. There was something ingratiating about his voice that entranced listeners and inspired a whole generation of male vocalists to try to approximate his supple sensuality and flowing melisma. (These would include David Ruffin, Johnnie Taylor, Otis Redding, Bobby Womack, Lou Rawls, and Jerry Butler.) (79)

Think of Cooke’s use of melisma with the monosyllabic word “You” in his hit “You Send Me.”

However, in popular singers less gifted than Sam Cooke, excessive (over) use of melisma results in melismania, defined by Michael Jarrett as

an obsessive compulsive disorder characterized by multiplying the notes sung to every syllable of text; melisma taken to excess.... melismania

. . . seeks to manufacture authenticity—to signify belief in the face of unbelief—through intense virtuosity . . . it creates rampant “affective inflation” that subverts its own efforts.... melismania is a particularly audible expression of what Lawrence Grossberg calls "sentimental inauthenticity." (82-83)

Melismania is variously known as “Mariah Carey Syndrome” or “Whitney Houston Syndrome,” although among Caucasians it is known as “Boltonism.”

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

Melismania

Monday, July 7, 2008

Peace & Love

Today, July 7, is Ringo Starr's 68th birthday (born 1940)--Happy Birthday, Ringo! According to his official website, the Beatles' former drummer was asked recently by Access Hollywood what he hoped to receive for his birthday this year. His answer? "Just more Peace & Love." He said, "it would be really cool if everyone, everywhere, wherever they are, at noon on July 7 make the peace sign and say 'Peace & Love'." Therefore, wherever you are in the world, join him in making the peace sign and saying, shouting, writing or quietly thinking his birthday wish: "Peace & Love."

Today, July 7, is Ringo Starr's 68th birthday (born 1940)--Happy Birthday, Ringo! According to his official website, the Beatles' former drummer was asked recently by Access Hollywood what he hoped to receive for his birthday this year. His answer? "Just more Peace & Love." He said, "it would be really cool if everyone, everywhere, wherever they are, at noon on July 7 make the peace sign and say 'Peace & Love'." Therefore, wherever you are in the world, join him in making the peace sign and saying, shouting, writing or quietly thinking his birthday wish: "Peace & Love."

Meanwhile, according to a report published yesterday in the TimesOnline, Ringo's birthplace at No. 9 Madryn Street, Liverpool, in an area of mid-Victorian Era buildings, where he was born Richard Starkey 68 years ago, is apparently to be demolished after a decision by English Heritage not to list it. According to the TimesOnline report:

Starr lived in Madryn Street for the first four years of his life before he and his mother moved around the corner to Admiral Grove. English Heritage’s main reason for rejecting the listing request, therefore, is that Madryn Street has no real links with the Beatles.

But according to additional information in the report, fellow Liverpudlians turned against Ringo when

he made dismissive comments about Liverpool on Jonathan Ross’s BBC1 show in January, saying there was “nothing” he missed about the place. A shrubbery sculpture of the drummer was later beheaded.

Apparently it doesn't pay to be honest. Perhaps as a Liverpudlian himself, Sir Paul ought to intercede and go about saving Ringo's birthplace, in deference to the the old adage, "honesty is the best policy."

Sunday, July 6, 2008

The Art of Noise

Introduced to the rock world at the Monterey Pop Festival, held June 16-18 1967, the Moog synthesizer was the most sophisticated and expensive noisemaking machine ever invented. Although seldom considered as a noisemaker, that is more or less how the synthesizer was initially perceived, given its first uses in popular music were weird and unusual sounds. There were various noisemaking machines introduced earlier, of course: Bebe and Louis Barron, for instance, were accomplished at using electronic noisemaking devices, creating the unearthly sounds—i.e., noises—used on the soundtrack to MGM’s SF classic Forbidden Planet (1956). But even before them, Spike Jones fired guns and banged pots and pans (among other things) when he set out to “murder the classics.” Other accomplished noisemakers include John Cage, Harry Partch, Frank Zappa’s beloved Edgar Varèse (pictured), Sun Ra, Yoko Ono, and of course Lou Reed, whose Metal Machine Music (1975) would have been inconceivable without these earlier composers preparing the way.

Introduced to the rock world at the Monterey Pop Festival, held June 16-18 1967, the Moog synthesizer was the most sophisticated and expensive noisemaking machine ever invented. Although seldom considered as a noisemaker, that is more or less how the synthesizer was initially perceived, given its first uses in popular music were weird and unusual sounds. There were various noisemaking machines introduced earlier, of course: Bebe and Louis Barron, for instance, were accomplished at using electronic noisemaking devices, creating the unearthly sounds—i.e., noises—used on the soundtrack to MGM’s SF classic Forbidden Planet (1956). But even before them, Spike Jones fired guns and banged pots and pans (among other things) when he set out to “murder the classics.” Other accomplished noisemakers include John Cage, Harry Partch, Frank Zappa’s beloved Edgar Varèse (pictured), Sun Ra, Yoko Ono, and of course Lou Reed, whose Metal Machine Music (1975) would have been inconceivable without these earlier composers preparing the way.

Hence the Moog synthesizer can be considered as simply another means of making noise, albeit a highly sophisticated one, and all noisemaking ritual has its anthropological roots in the charivari. According to answers.com, charivari is defined as, "A mock serenade (e.g. for newlyweds) of loud, discordant noises using pots and pans, cowbells, guns and other noisemakers; by extension, any cacophony of out-of-tune noises." The word is French, from the Old French for “hubbub,” perhaps from Late Latin carībaria, headache, from Greek karēbariā: karē, head + barus, heavy.

Here’s what Claude Lévi-Strauss, in his essay “Divertissement on a Folk Theme” (from The Raw and the Cooked, University of Chicago Press, 1969), says about the charivari:

The Encyclopédie compiled by Diderot and d’Alembert defines “charivari” as follows:

The word . . . means and conveys the derisive noise made at night with pans, cauldrons, basins, etc., in front of the houses of people who are marrying for the second or third time or are marrying someone of a very different age from themselves. (288)

One can see from Levi-Strauss’s definition the origin of the meaning of charivari (in American English, shivaree) as "mock serenade": if the serenade celebrates romantic love, the charivari satirizes it.

The recent re-issue on CD of Mort Garson and Jacques Wilson’s charivari, The Wozard of Iz (original release: 1968), subtitled “An Electronic Odyssey” and produced by electronic music pioneer Bernie Krause, is a good illustration of the early uses of the Moog synthesizer. A media satire using The Wizard of Oz to structure the heroine's journey to the "Upset Strip," The Wozard of Iz is badly dated by virtue of its (heavy) use of late 60s slang and for being too obviously created for juvenile audiences (nothing about it is in the least way subtle), but it is interesting nonetheless as an illustration of how the synthesizer was perceived as nothing more, early on in its history, as a novelty. Most certainly it was Wendy Carlos’ Switched-On Bach, released a couple of months after The Wozard of Iz in 1968, that first gave the synthesizer musical credibility, demonstrating to a skeptical audience that the synthesizer was something much other than an expensive toy.

I made the observation in an earlier post that early on in its history any unconventional or radically new knowledge is at first perceived to be a bad joke--Freud's theory of psychoanalysis, for instance, and Darwin's theory of human beings evolving from monkeys were, in fact, both considered bad jokes. I suggested that popular music's appropriation of the "psychedelic experience" was initially perceived as a bad joke: the first albums containing the word "psychedelic," such as the Blues Magoos' "Psychedelic Lollipop," used the word in a joking way. The idea of the joke permeates early albums claiming to be psychedelic, for instance, Friar Tuck and His Psychedelic Guitar (1967), The Animated Egg (1967), Hal Blaine's Psychedelic Percussion (1967), and so on. The Wozard of Iz illustrates the same idea: like these other, aforementioned records, it sold poorly, because it lacked both credibility and substance, and was just so much noisemaking. Conversely, Wendy Carlos' Switched-On Bach sold well because it was straight. Unlike Spike Jones, who set out to "murder the classics," Switched-On Bach approached the music with the utmost seriousness, as high art, and the role of the synthesizer as a noisemaking toy was minimized, if not absent altogether. In other words, Wendy Carlos set out to do anything but perform a charivari.

Saturday, July 5, 2008

"Dixie"

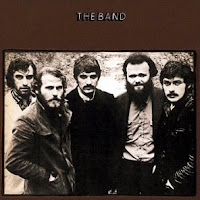

Having listened intently the past few days to the Band’s first album, Music From Big Pink (1968), today I found myself compelled to begin listening to the Band’s eponymous second album (released September 1969), the album that contains one of the Band’s most famous songs, The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down. A wonderfully dynamic, dramatic, and utterly compelling song, it was famously covered by Joan Baez, who had a hit single with the song about a year and a half after The Band's release. It was subsequently covered by Johnny Cash on his album John R. Cash (1975). In the context of the late 1960s and the Vietnam War, "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," while set during the days after the end of the bloody American Civil War, was generally interpreted as a song having an anti-war sentiment, while also invoking the Biblical parable of Cain and Abel. Presumably, the song was an attempt to identify and overcome the tensions of an American population divided in its support for the Vietnam War, to speak to both groups in a way that also acknowledged their mutual sense of patriotism.

Having listened intently the past few days to the Band’s first album, Music From Big Pink (1968), today I found myself compelled to begin listening to the Band’s eponymous second album (released September 1969), the album that contains one of the Band’s most famous songs, The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down. A wonderfully dynamic, dramatic, and utterly compelling song, it was famously covered by Joan Baez, who had a hit single with the song about a year and a half after The Band's release. It was subsequently covered by Johnny Cash on his album John R. Cash (1975). In the context of the late 1960s and the Vietnam War, "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," while set during the days after the end of the bloody American Civil War, was generally interpreted as a song having an anti-war sentiment, while also invoking the Biblical parable of Cain and Abel. Presumably, the song was an attempt to identify and overcome the tensions of an American population divided in its support for the Vietnam War, to speak to both groups in a way that also acknowledged their mutual sense of patriotism.

Like the Bible's Cain, the singer of "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," Virgil Caine (Cain?), is a farmer:

Virgil Caine [Cain?] is the name

And I served on the Danville train

'Til Stoneman’s cavalry came

And tore up the tracks again

In the winter of ‘65

We were hungry, just barely alive

By May the 10th Richmond had fell

It’s a time I remember oh so well

Chorus:

The night they drove Old Dixie down

And the bells were ringing

The night they drove Old Dixie down

And the people were singin’

They went Na, La, La, La, Na, Na . . .

Back with my wife in Tennessee

When one day she called to me

“Virgil quick come see—there goes Robert E. Lee”

Now I don’t mind choppin’ wood

And I don't care if the money’s no good

You take what you need

And you leave the rest

But they should never

Have taken the very best

[Chorus]

Like my father before me

I’m a workin’ man

Like my brother before me

Who took a rebel stand

He was just eighteen, proud and brave

But a Yankee laid him in his grave

I swear by the mud below my feet

You can't raise a [Cain?] Caine back up when he's in defeat

[Chorus]

The key poetic figure in the song is, of course, Dixie. There are few popular songs in American history more controversial than "Dixie," a song both adored and despised. Improbably, "Dixie" is a song that, prior to the Civil War, received ovations from both abolitionist Republicans and proslavery Democrats. After the Southern succession, it was adopted by the Confederacy as its national anthem. The song was played at Jefferson Davis's inauguration, but Abraham Lincoln so loved the song that he had it played at his second inauguration.

According to Michael Jarrett, "Dixie" was introduced on the Broadway stage on 4 April 1859 by Daniel Emmett, the founder of the first professional blackface minstrel troupe, and was an instant hit. But, as Jarrett observes,

...the popularity of "Dixie" resulted from the song's basic slipperiness. It seemed eager to serve all sorts of agendas and capable of insinuating itself into a variety of contexts. . . . "Dixie" is far more redolent of meaning than it is explicity meaningful. It functions as a poetic image. Generations of Americans, nostalgically drawn to the idyllic scene it calls them to conjure, have revered it. And generations, enraged and offended by the antebellum stereotypes it asks them to celebrate, have reviled it. (27)

Hence, the power of Dixie is in its multivalency: inherently ambiguous, it is a sentimental anthem associated with the American South, but also, consequently, a symbol of racism. But rather than be stymied by the figure's inherent cultural ambiguity, Mike Jarrett thinks we ought to listen to the song "anew." He writes:

How about straight, as a song of exile? Heard this way, it echoes psalms of captivity found in the Old Testament and anticipates the lamentations that abound in blues and, especially, reggae. Or how about ironically, as a signifying song? "Oh, I wish I was in the land of cotton. Yeah, like hell I do!" (28)

The slippery multivalency of "Dixie" allowed Mickey Newbury to incorporate the song into his well-known medley, "An American Trilogy," a song that, beginning in 1972, Elvis began performing during his live concerts. A portmanteau song celebrating the diversity of America, Newbury's "An American Trilogy" is composed of three songs: "Dixie" (South), "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" (North), and "All My Trials" (the individual citizen).

I raise these issues because today while listening to "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," I wondered why Elvis had never covered the song. Certainly he was capable of singing it. Certainly he was capable of singing it well. Did he reject it because he perceived it as a song of amelioration, a song about mending fences, and hence too much associated with the moderate Left (i.e., Joan Baez)? I turned to Elvis's rendition of "An American Trilogy," thinking that this song might well have been his "answer" song to the Band's earlier song. Having watched the Band's rendition of "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" as performed in The Last Waltz (1978; filmed late 1976,)--available on youtube.com--it struck me that there was a remarkable similarity between the orchestration and staging of The Last Waltz and the orchestration and staging of Elvis's Las Vegas shows, especially his arrangement of "An American Trilogy." In other words, the Band's performance of "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" in The Last Waltz was influenced by Elvis's earlier response to that very song, with his version of "An American Trilogy," also available on youtube.

Tuesday, July 1, 2008

My Albums Were Fair and Had Pink Sun in Their Hair

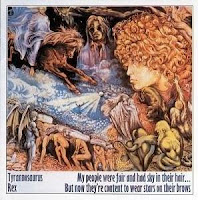

Previously, in my blog entries of May 16 and May 31, I have discussed my experiment of trying to listen to all the rock and R&B albums released in the calendar year 1968 in the order, as best as I can determine, in which they were released. I'll refer readers to the earlier blogs for an explanation of the motivation for such an unusual (and self-indulgent) project. At any rate, it occurred to me this morning that I hadn’t posted July’s listening schedule, which can be found below. As I’ve stated before, I cannot claim that my list is infallible, but I continue to work on it and to try and improve it. What I've discovered is that there were dozens of albums released during the months of July and August--more so in terms of numbers of releases in a single month than in any previous month--so as you can see, July’s list is rather long (assuming the information I've come across is accurate). First up is The Band’s classic Music From Big Pink, released forty years ago today, on July 1, 1968. Here's what I have put together for July:

Previously, in my blog entries of May 16 and May 31, I have discussed my experiment of trying to listen to all the rock and R&B albums released in the calendar year 1968 in the order, as best as I can determine, in which they were released. I'll refer readers to the earlier blogs for an explanation of the motivation for such an unusual (and self-indulgent) project. At any rate, it occurred to me this morning that I hadn’t posted July’s listening schedule, which can be found below. As I’ve stated before, I cannot claim that my list is infallible, but I continue to work on it and to try and improve it. What I've discovered is that there were dozens of albums released during the months of July and August--more so in terms of numbers of releases in a single month than in any previous month--so as you can see, July’s list is rather long (assuming the information I've come across is accurate). First up is The Band’s classic Music From Big Pink, released forty years ago today, on July 1, 1968. Here's what I have put together for July:

The Band, Music From Big Pink 7/1

Creedence Clearwater Revival, Creedence Clearwater Revival 7/5

Tyrannosaurus Rex, My People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair... 7/5

The Nice, The Thoughts of Emerlist Davjack

The Doors, Waiting for the Sun 7/11

Buffalo Springfield, Last Time Around

Family, Music in a Doll’s House

Nilsson, Aerial Ballet

Phil Ochs, Tape From California

The International Submarine Band, Safe At Home

The Grateful Dead, Anthem of the Sun

Bloomfield-Kooper-Stills, Super Session 7/22

The Moody Blues, In Search of the Lost Chord 7/26

The Byrds, Sweetheart of the Rodeo 7/29

Cream, Wheels of Fire 7/29

As you can see, a number of historically significant records were issued in July 1968. As usual, corrections and additions are welcome.

List emended 7/22/08

Thursday, June 26, 2008

"For What It's Worth"

Perhaps one of the best-known songs of the decade of the 1960s is Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth,” released as a 45 rpm single in January 1967 (not included on the first pressing of the band's first LP, it became such a huge hit that later pressings of the album replaced one track and included it instead). It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that "For What It's Worth" appears on the soundtrack of just about every documentary one can find about that tumultuous decade. I think a good, concise interpretation of the song--the complete discussion of which can be found here--is as follows:

Perhaps one of the best-known songs of the decade of the 1960s is Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth,” released as a 45 rpm single in January 1967 (not included on the first pressing of the band's first LP, it became such a huge hit that later pressings of the album replaced one track and included it instead). It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that "For What It's Worth" appears on the soundtrack of just about every documentary one can find about that tumultuous decade. I think a good, concise interpretation of the song--the complete discussion of which can be found here--is as follows:

The . . . song . . . manages to warn of increasing polarization and violence in American society, without taking any stand other than that of acceptance of diversity and free speech. In other words, it comments on politics without itself being political.

I believe this to be a standard interpretation, but I find the claim that the song "comments on politics without itself being political" to be extremely revealing. Interestingly, the historical origins of the song don’t especially shed light on its meaning, although it clearly partakes of what was referred to at the time as “youth culture.”

The song was inspired by an event in November 1966, the year during which Buffalo Springfield started playing as the house band at the famed Whiskey A Go-Go on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles. At the dawn of the psychedelic era, on Saturday, November 12, 1966, near a club at the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Crescent Heights named Pandora’s Box (pictured), supposedly 1,000 youthful demonstrators (I say “supposedly” as the number strikes me as dubiously high) erupted in protest against the perceived repressive enforcement of recently invoked curfew laws. As I understand it, these curfew laws were passed in order to get a handle on underage drinking going on at some of the Sunset Strip clubs catering to a youthful clientele (a painfully banal explanation, to be sure). Apparently some business owners wanted the authorities to pass laws that would help rid the Sunset Strip of vast numbers of loitering teenagers as well as the growing number of "hippies," the pan-handling presence of which were discouraging patrons from attending their drinking and dining establishments.

Referred to as the “Sunset Strip Riot”—inspiring the movie Riot on Sunset Strip (1967)—apparently the event was characterized by some rather typical youthful expressions of outrage: rock throwing (where did the rocks come from?), an attempt to set fire to a city bus filled with terrified passengers, and various other acts of destructive vandalism. The event was referred to in the L. A. press as a “riot,” perhaps to link the disruptive moment to the more destructive and socially significant Watts riots of the year before. The net result was that within the year—by August of 1967—Pandora’s Box was demolished and paved over to make an easy access road to Crescent Heights off of Sunset Boulevard. That's one way to solve a problem.

As is widely known, the so-called “Sunset Strip Riot”—and perhaps the Watts Riots the year before—inspired then Buffalo Springfield band member Stephen Stills to write “For What It’s Worth,” recorded about three weeks after the so-called "riot," on December 5, 1966. The lyrics are so well known it hardly seems necessary to reproduce them, but I do so below for the sake of convenience:

There’s something happening here

What it is ain’t exactly clear

There’s a man with a gun over there

Telling me I got to beware

I think it’s time we stop, children, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down

There’s battle lines being drawn

Nobody’s right if everybody’s wrong

Young people speaking their minds

Gettin’ so much resistance from behind

It’s time we stop, hey, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down

What a field day for the heat

A thousand people in the street

Singing songs and carrying signs

Mostly say, hooray for our side

It’s time we stop, hey, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down

Paranoia strikes deep

Into your life it will creep

It starts when you’re always afraid

You step out of line, the Man come and take you away

We better stop, hey, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down

Although famous, and strongly associated with the decade of the 1960s, I find this a hard song on which to get a critical handle, especially as any sort of trenchant "social criticism." For one thing, what’s the level of intellectual commitment to the so-called issue of freedom of expression (a value that is, of course, never actually named)? It seems more like a sum of commonplaces strung together rather than expressing any deeply felt social outrage. The title, especially, doesn’t help: the colloquial expression, “For What It’s Worth,” offers only a minimal commitment to an idea; it seems a strangely noncommittal title for a song that putatively contains acute political insight. A better title might be, “My Two Cents’ Worth,” as that phrase more accurately suggests the level of extent of the emotional engagement with the issue(s). No doubt it was influenced by the overt political protest characteristic of 1960s folk music, but it lacks the clear statement of a political position that these songs make explicit. In this sense, we can see that it positions itself somewhere between outright polemic and disinterested social observation: “Nobody’s right if everybody’s wrong.” The line reminds me of something a fence-riding high school guidance counselor told me in response to the Kent State campus shootings in 1970. If it is considered, narrowly, merely as a response to the so-called "Sunset Strip Riot," then it amounts to nothing more than an argument insisting that teenagers ought to be able to have fun when they want to have fun.

In retrospect, the whole song smacks of fence-riding. In Canto III of Dante’s Inferno, the fence-riders—named "Neutrals" in J. D. Sinclair's translation to desribe those who never took a position in life—are situated in the vestibule to Hell, Hell refusing to let them in because they never made a decision on anything during their lives.

To properly understand the song, I think, we need to focus elsewhere than on politics, and recognize that it owes something to the ideas in Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1962), and Kesey’s use of the mental institution as a metaphor for everyday life: “You step out of line, the Man come and take you away.” Think of the 60s novelty song “They're Coming to Take Me Away, Ha-Haaa!”—that was, incidentally, released in July 1966, four months before the Sunset Strip Riot, and about five months before Buffalo Springfield recorded "For What It's Worth." One of the novelty song’s lyrics refers to the “funny farm,” which is, of course, a colloquial reference to an asylum. The narrator of Cuckoo’s Nest, Chief Bromden, uses the phrase “the Combine” to refer to the large, invisible system of coercion that society uses to control and manipulate individuals. I’ve written a great deal, recently, about Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, so I don’t think that his fame and notoriety during this period in the 1960s needs rehearsing. The way authority is referred to only in the abstract--"man with a gun," "resistance from behind," "the heat," the Man"--also supports the idea that the song refers to the repressive operations of "the Combine."

If nothing else, a close analysis of the song warns against any attempt to transform pop songs into agitprop.