Serendipitously, just a couple of minutes after posting today's blog entry, “Audio/Vison,” I checked my email to find that I’d received the Sunday e-issue of The Los Angeles Times, which had a review of a new book (cover is pictured to the left) entitled The San Francisco Tape Music Center: 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-Garde, Ed. David W. Bernstein (U of California Press/Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute), an account of the pioneering electronic music center in San Francisco. Since a number of issues explored in the book are relevant to my previous blog on ambient music—particularly the role of technology and the recording studio—I thought I’d provide readers with a link to the review. Click on the book title above to go the University of California website for further information about the new title. List price of the book is $65.00, but may be substantially discounted at certain on-line vendors.

Serendipitously, just a couple of minutes after posting today's blog entry, “Audio/Vison,” I checked my email to find that I’d received the Sunday e-issue of The Los Angeles Times, which had a review of a new book (cover is pictured to the left) entitled The San Francisco Tape Music Center: 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-Garde, Ed. David W. Bernstein (U of California Press/Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute), an account of the pioneering electronic music center in San Francisco. Since a number of issues explored in the book are relevant to my previous blog on ambient music—particularly the role of technology and the recording studio—I thought I’d provide readers with a link to the review. Click on the book title above to go the University of California website for further information about the new title. List price of the book is $65.00, but may be substantially discounted at certain on-line vendors.

Sunday, July 27, 2008

Audio/Vision: Addendum

Audio/Vison

Ambient music is generally defined as music in which the sounds are as equally important as the notes, its purpose being to invoke an “atmosphere” or to enhance an “environment.” It was Brian Eno who named this kind of music ambient (from the Latin ambire, "to go around") saying it consisted of sounds poised on “the cusp between melody and texture.” While there are any number of artists one could name who contributed to the development of ambient music (what Erik Satie in an earlier age called musique d’ameublement, “furniture music”), for Eno the major contributor to the development of ambient music is that “grand new musical instrument, the recording studio” (30). Eric Tamm, in Brian Eno: His Music and the Vertical Color of Sound, writes:

Ambient music is generally defined as music in which the sounds are as equally important as the notes, its purpose being to invoke an “atmosphere” or to enhance an “environment.” It was Brian Eno who named this kind of music ambient (from the Latin ambire, "to go around") saying it consisted of sounds poised on “the cusp between melody and texture.” While there are any number of artists one could name who contributed to the development of ambient music (what Erik Satie in an earlier age called musique d’ameublement, “furniture music”), for Eno the major contributor to the development of ambient music is that “grand new musical instrument, the recording studio” (30). Eric Tamm, in Brian Eno: His Music and the Vertical Color of Sound, writes:

Eno has singled out a number of musicians who . . . consciously tried to realize the potential of . . . the recording studio: Glenn Gould (whose technique of recording many performances and editing them together Eno greatly admired); Jimi Hendrix (who would fill as many as twenty-six separate tracks on a thirty-two-track tape recorder with guitar solos, then begin the real creative process of blending, mixing, and deleting); Phil Spector (who “understood better than anybody that a recording could do things that could never actually happen”); the Beach Boys, the Jefferson Airplane, and the Byrds (whose experimental and psychedelic approach Eno appreciated); the Beatles (whose 1966 album Revolver, recorded on four-track with George Martin at the controls, Eno described as “my favourite Beatles album”); and Simon and Garfunkel (“The song ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ [1970] is perfection in its way. I’m told it took 370 hours of studio time to record—that’s longer than most albums, but it is such an incredible tour de force....” (30-31)

Eno’s remark about Phil Spector—he “understood better than anybody that a recording could do things that could never actually happen”—is an insight shared by the very best filmmakers, those who will sacrifice narrative logic for the sake of a powerful image (e.g., Andrei Tarkovsky, pictured) and also invent not mere sound tracks, but audio tracks (e.g., David Lynch), that is, use the grand musical instrument of the recording studio to the same degree as the motion picture camera.

Representative Films Featuring Masterful Audio/Vision:

Chris Marker/Trevor Duncan, La Jetée (1962)

Michelangelo Antonioni/Giovanni Fusco and Vittorio Gelmetti, Red Desert (1964)

Stanley Kubrick/H.L. Bird and Winston Ryder, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

George Lucas/Walter Murch, American Graffiti (1973)

Terrence Malick/George Tipton, Badlands (1973)

David Lynch/Alan R. Splet, Eraserhead (1977)

Andrei Tarkovsky/Eduard Artemev, Stalker (1979)

Francis Ford Coppola/Walter Murch and Carmine Coppola, Apocalypse Now (1979)

Brian Eno, Thursday Afternoon (1984)

Michael Mann/Elliot Goldenthal, Heat (1995)

Terrence Malick/Craig Berkey and James Horner, The New World (2005)

Friday, July 25, 2008

Wah

Although initially invented in response to a request by trumpet player Clyde McCoy, who'd asked the Vox corporation for an electronic device that could simulate the sound of a muted trumpet for use with a keyboard, the wah-wah pedal was quickly appropriated in the late 1960s by rock guitarists. In doing so, they defined both a musical period and instituted an aesthetic, one that, when realized through guitar virtuosos such as Jimi Hendrix and Eddie Hazel of Funkadelic, has been referred to as "psychedelic soul." According to Art Thompson, in an article published in Guitar Player Magazine titled "Wah: The Pedal That Wouldn't Die" (May 1992; my source for the article can be found here), Vox was the first company to have success with the wah-wah pedal. Thompson writes: "Vox's entry into the wah-wah pedal business came about thanks to Brad Plunkett, a twenty five year old engineer at Thomas Organ. Around '66 Plunkett was working on a circuit to replace the 3-position MRB, or voicing switch, with a less expensive potentiometer.... To test the idea, a guitar was plugged in and, as Plunkett describes 'all of a sudden people came running in to see what was making this sound--they just freaked out on it.'" Thompson continues:

Although initially invented in response to a request by trumpet player Clyde McCoy, who'd asked the Vox corporation for an electronic device that could simulate the sound of a muted trumpet for use with a keyboard, the wah-wah pedal was quickly appropriated in the late 1960s by rock guitarists. In doing so, they defined both a musical period and instituted an aesthetic, one that, when realized through guitar virtuosos such as Jimi Hendrix and Eddie Hazel of Funkadelic, has been referred to as "psychedelic soul." According to Art Thompson, in an article published in Guitar Player Magazine titled "Wah: The Pedal That Wouldn't Die" (May 1992; my source for the article can be found here), Vox was the first company to have success with the wah-wah pedal. Thompson writes: "Vox's entry into the wah-wah pedal business came about thanks to Brad Plunkett, a twenty five year old engineer at Thomas Organ. Around '66 Plunkett was working on a circuit to replace the 3-position MRB, or voicing switch, with a less expensive potentiometer.... To test the idea, a guitar was plugged in and, as Plunkett describes 'all of a sudden people came running in to see what was making this sound--they just freaked out on it.'" Thompson continues:

Apparently Vox management saw lots of potential in this new gizmo, and it was subsequently introduced as the Clyde McCoy wah-wah pedal.... These early pedals were manufactured in Italy and have a picture of Clyde on the bottom. They were distributed in the U.S. by the Thomas Organ Company.... Vox also offered a non-signature model around this time that simply said "Wah" on the bottom plate; it was also made in Italy.

About the wah-wah pedal's subsequent development, Thompson writes:

The introduction of the Vox Cry Baby pedal around 1968 came about because the U.S. distributor, Thomas Organ, and the European distributor, JMI, both wanted to sell the wah-wah but neither wanted the other to have the same pedal. Vox solved this by slapping the Cry Baby name on the same model for the American market. The story goes that when Vox needed a new name for the pedal, they asked one of their distributors to describe the wah's sound. The response was "it sounds like a baby crying." Also at this time, Vox and Thomas Organ introduced a new model designated V846 that used a Japanese inductor made by TDK instead of the Italian made inductor. Most purists agree that this change degraded the sound of these pedals, but in the informal tests we conducted, our favorite (because of its almost human vocal quality and vomiting sounds) was an excellent sounding V846....The next major change ocurred when Vox came out with the King Wah, the first unit made completely in the United States.... Many of these devices offered extra sounds like fuzz, sirens, surf, tornado, and God knows what else.... As the late '70s approached, the wah effect was becoming unhip, and the number of manufacturers dropped accordingly.

Early Recordings Featuring the wah-wah pedal

Cream - “White Room” Wheels of Fire (1968)

The Jimi Hendrix Experience - “Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)” Electric Ladyland (1968)

The Temptations - “Cloud Nine” Cloud Nine (1968)

Tommy James and the Shondells - “Crimson & Clover” Crimson & Clover (1968)

Sly and the Family Stone - “Sex Machine” Stand! (1969)

Blind Faith - “Presence of the Lord” Blind Faith (1969)

Chicago - “25 or 6 to 4” Chicago II (1970)

Santana - “Samba Pa Ti” Abraxas (1970)

Funkadelic - “Maggot Brain” Maggot Brain (1971)

Isaac Hayes - “Theme From Shaft” Shaft (Soundtrack) (1971)

In 1972, Isaac Hayes' "Theme from Shaft" won an Academy Award for "Best Original Song," thus making it the first rock song featuring a wah-wah pedal to be honored with a major award.

Wednesday, July 23, 2008

Border Blasters

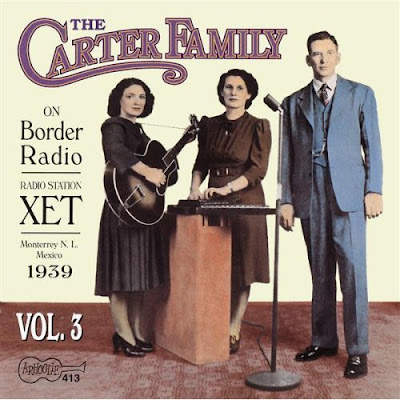

“Border blasters” is the phrase broadcasters use to refer to the so-called “X stations”—Mexican radio stations—because the call letters of every Mexican radio station begins with an X. Otherwise known as border radio, perhaps the best known of the border blasters was station XERB, the model for the station featured in George Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973). Peculiar to the United States, border radio inspired countless rock and pop musicians, as the Mexican stations largely played music suppressed by the corporate owned, commercially oriented radio stations in the United States: not only were countless teenagers able to hear country and western, played by the likes of the Carter Family (pictured on the CD cover of Vol. 3 of the XET recordings) and Hank Williams, but blues musicians such as Howlin’ Wolf and John Lee Hooker. George Lucas, born in 1944 and raised in Modesto, California, grew up listening to the Xs, many of which featured eccentric disc jockeys such as Wolfman Jack, who would eventually make an appearance in American Graffiti. Lucas was one of those kids who listened to “50,000 watts out of Mexico,” as the Blasters sing in “Border Radio.”

“Border blasters” is the phrase broadcasters use to refer to the so-called “X stations”—Mexican radio stations—because the call letters of every Mexican radio station begins with an X. Otherwise known as border radio, perhaps the best known of the border blasters was station XERB, the model for the station featured in George Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973). Peculiar to the United States, border radio inspired countless rock and pop musicians, as the Mexican stations largely played music suppressed by the corporate owned, commercially oriented radio stations in the United States: not only were countless teenagers able to hear country and western, played by the likes of the Carter Family (pictured on the CD cover of Vol. 3 of the XET recordings) and Hank Williams, but blues musicians such as Howlin’ Wolf and John Lee Hooker. George Lucas, born in 1944 and raised in Modesto, California, grew up listening to the Xs, many of which featured eccentric disc jockeys such as Wolfman Jack, who would eventually make an appearance in American Graffiti. Lucas was one of those kids who listened to “50,000 watts out of Mexico,” as the Blasters sing in “Border Radio.”

As Gene Fowler and Bill Crawford point out in their book Border Radio, Mexican radio stations developed in the late 1920s as a response to monopolistic American and Canadian corporations carving up the frequencies—in doing so, shutting out Mexico—and, subsequently, in the 1930s, to federal regulations that required standardization of the format and proscription of the content. Station XED, in Reynosa, began transmitting in 1930. Fowler and Crawford write:

The men who first moved to the border began their broadcasting careers when the federal regulatory agency was but a twinkle in Herbert Hoover’s eye. These media trailblazers deeply resented the monopolistic power of the networks and the increasing government interference in their activities. They traveled from the hinterlands of Iowa, Kansas, and Brooklyn to a territory beyond the pale of American law, a sparsely populated land of ocotillo, grapefruit, and Angora goats—la frontera, the border.

Border radio operators came up with a unique method of sidestepping U.S. broadcasting restrictions: They built their stations just across the border, in Mexican territory, and worked out special licensing arrangements with the broadcasting authorities in Mexico City, whom they found to be much more agreeable than the stuffed shirts at the Federal Radio Commission. Like all radio stations licensed in Mexico, the border stations were given call letters beginning with XE, a brand that added to their mystique. To compete with the wide coverage of the established multistation networks, these operators created what were essentially single-station networks, stations with such extraordinary power that their signals could cover much of the United States and, in some cases, most of the world. Border radio operators accomplished this feat by hiring expert engineers to build special transmitters. While most radio outlets in the United States broadcast over transmitters with about 1,000 watts of power, border stations boomed their programming across America with transmitters humming at as much as 1,000,000 watts [station XERA].

Essential Recordings (with thanks to Mike Jarrett)

ZZ Top, “Heard It on the X” Fandango (Warner Bros., 1975)

Warren Zevon, “Carmelita” Warren Zevon (Asylum, 1976)

The Blasters, “Border Radio” The Blasters (Slash, 1981)

Wall of Voodoo, “Mexican Radio” Call of the West (I.R.S., 1982)

Dave Alvin, “Border Radio” King of California (Hightone, 1994)

Essential Viewing

American Graffiti (1973)

Border Radio (1987)

Pump Up the Volume (1990)

Empire of the Air: The Men Who Made Radio (Ken Burns, 1991)

Tuesday, July 22, 2008

The Mellotron

The Mellotron, a keyboard instrument that was featured in early psychedelic music and later became an essential fixture of “Progressive” bands, was made possible by one of the spoils of World War II—electromagnetic tape. As Michael Jarrett notes in Sound Tracks (1998), "When U.S. troops invaded Radio Luxembourg, they "liberated" a tape machine and shipped it to the Ampex Corporation; further development was financed by Bing Crosby" (214). Technically considered, the Mellotron is a polyphonic, sample-playback keyboard system, the basis of which is a large bank of pre-loaded electromagnetic audio tapes, each of which consists of a pre-recorded sound. Each of the several magnetic tapes has roughly eight seconds of playing time: early user manuals strongly recommended that no key should be held for more than ten seconds. Playback heads underneath each of the keys allowed for the playing of the pre-recorded sounds, hence the reason it is considered a "sample-playback" system. Early Mellotron models, the MK-I and the MK-II, contained two keyboards set side-by-side: the right keyboard consisted of various selectable "instrumental" sounds (e.g., strings, flutes, various brass instruments), while the left keyboard consisted of rhythm tracks. The first Mellotrons--intended for the home, not for the arduous rock concert circuit--were made in Birmingham, England (although the prototype was initially developed in the United States), the reason why the earliest uses of the instrument were by British bands. Musician Mike Pinder (pictured above in the foreground, with the Moody Blues, playing a Mellotron MK-II) worked for Streetly Electronics, the company that manufactured the Mellotron, for about a year and half before joining the Moody Blues in 1967; he and the band are largely responsible for popularizing the Mellotron in popular music. Like the Moog synthesizer, also an electronic instrument, the Mellotron underwent development and refinement. The years of manufacture of the various models of the Mellotron are as follows:

The Mellotron, a keyboard instrument that was featured in early psychedelic music and later became an essential fixture of “Progressive” bands, was made possible by one of the spoils of World War II—electromagnetic tape. As Michael Jarrett notes in Sound Tracks (1998), "When U.S. troops invaded Radio Luxembourg, they "liberated" a tape machine and shipped it to the Ampex Corporation; further development was financed by Bing Crosby" (214). Technically considered, the Mellotron is a polyphonic, sample-playback keyboard system, the basis of which is a large bank of pre-loaded electromagnetic audio tapes, each of which consists of a pre-recorded sound. Each of the several magnetic tapes has roughly eight seconds of playing time: early user manuals strongly recommended that no key should be held for more than ten seconds. Playback heads underneath each of the keys allowed for the playing of the pre-recorded sounds, hence the reason it is considered a "sample-playback" system. Early Mellotron models, the MK-I and the MK-II, contained two keyboards set side-by-side: the right keyboard consisted of various selectable "instrumental" sounds (e.g., strings, flutes, various brass instruments), while the left keyboard consisted of rhythm tracks. The first Mellotrons--intended for the home, not for the arduous rock concert circuit--were made in Birmingham, England (although the prototype was initially developed in the United States), the reason why the earliest uses of the instrument were by British bands. Musician Mike Pinder (pictured above in the foreground, with the Moody Blues, playing a Mellotron MK-II) worked for Streetly Electronics, the company that manufactured the Mellotron, for about a year and half before joining the Moody Blues in 1967; he and the band are largely responsible for popularizing the Mellotron in popular music. Like the Moog synthesizer, also an electronic instrument, the Mellotron underwent development and refinement. The years of manufacture of the various models of the Mellotron are as follows:

Mellotron Mark-I (1962-63)

Mellotron Mark-II (1964-67)

M-300 (1968-70)

M-400 (1970-86)

The M-400 model, first sold in 1970, become part of the signature sound of the so-called “Progressive” bands of the 1970s. This model included tape banks that could be removed with relative ease and loaded with banks containing different sounds, including percussion loops, sound effects, and other noises. Hence, like pop music itself, the Mellotron is a consequence of electromagnetic tape.

Ten representative rock songs featuring the Mellotron, 1967-1973:

1. The Beatles - “Strawberry Fields Forever” Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967)

2. The Moody Blues - “Nights in White Satin” Days of Future Passed (1967)

3. The Rolling Stones - “2000 Light Years From Home” Their Satanic Majesties Request (1967)

4. The Zombies - “Brief Candles” Odessey & Oracle (1968)

5. Cream - “Badge” Goodbye (1969)

6. David Bowie - “Space Oddity” Space Oddity (1969)

7. King Crimson - “Epitaph” In the Court of the Crimson King (1969)

8. Genesis - “Watcher of the Skies” Foxtrot (1972)

9. Lynyrd Skynyrd - “Tuesday’s Gone” pronounced 'lĕh-'nérd 'skin-'nérd (1973)

10. John Lennon - “Mind Games” Mind Games (1973)

For those interested, a short demonstration from the mid-60s of the Mellotron MK-II, can be found here, while an interesting history of the Mellotron, by Mike Pinder of the Moody Blues, can be found here.

Cheap Thrills and the Wonderful Undead

Previously, in my blog entries of May 16, May 31, and July 1 I have discussed my experiment of trying to listen to all the rock and R&B albums released in the calendar year 1968 in the order in which they were released. I'll refer readers to my earlier blog entries for the explanation for such an unusual project (and all the pitfalls inherent in such an ongoing activity). Since I've already assembled it, I've gone ahead and posted August’s listening schedule. As I’ve stated many times before, I cannot claim my list is infallible, but I continue to work on it and to try and improve it. What I've discovered is that there were many albums released during the months of July and August 1968--more so in terms of numbers of releases in a single month than in any previous month--so as you can see, August’s list is rather long (assuming the information I've come across is accurate). Here's the dozen albums I have put together for August 1968:

Previously, in my blog entries of May 16, May 31, and July 1 I have discussed my experiment of trying to listen to all the rock and R&B albums released in the calendar year 1968 in the order in which they were released. I'll refer readers to my earlier blog entries for the explanation for such an unusual project (and all the pitfalls inherent in such an ongoing activity). Since I've already assembled it, I've gone ahead and posted August’s listening schedule. As I’ve stated many times before, I cannot claim my list is infallible, but I continue to work on it and to try and improve it. What I've discovered is that there were many albums released during the months of July and August 1968--more so in terms of numbers of releases in a single month than in any previous month--so as you can see, August’s list is rather long (assuming the information I've come across is accurate). Here's the dozen albums I have put together for August 1968:

The Beach Boys, Stack-O-Tracks

The Bee Gees, Idea

Blue Cheer, Outsideinside

Country Joe & the Fish, Together

Donovan, In Concert

The Everly Brothers, Roots

The 5th Dimension, Stoned Soul Picnic

Fleetwood Mac, Mr. Wonderful

Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, You're All I Need

The Grateful Dead, [Two From the Vault] [8/23-24] [1992]

Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company, Cheap Thrills

Jeff Beck, Truth

Ten Years After, Undead