Monday, April 19, 2010

Cowry Shell

A Few Explicit Fetishes:

Joe Bennett and the Sparkletones – Black Slacks

Tony Bennett – Blue Velvet

Big Bopper – Chantilly Lace

Dee Clark – Hey Little Girl (In the High School Sweater)

David Allan Coe – Angels in Red

Derek and the Dominos – Bell Bottom Blues

Bob Dylan – Boots of Spanish Leather

The Eagles – Those Shoes

Brian Hyland – Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini

The Hollies – Long Cool Woman in a Black Dress

Kenny Owen – High School Sweater

Carl Perkins – Blue Suede Shoes

Mitch Ryder & The Detroit Wheels – Devil With A Blue Dress On

Rod Stewart – You Wear It Well

Royal Teens – Short Shorts

Conway Twitty – Tight Fittin’ Jeans

Sunday, April 18, 2010

Steal This Blog

In art and literature, self-referentiality is sometimes referred to as self-reflexivity, occurring when the artist or writer refers to the work in the context of the work itself – as does “The Song That Never Ends.” There are many children's songs that privilege recursivity and self-reflexivity, but there are also many great examples of self-reflexive pop songs as well. Perhaps the most well known of these songs is Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain,” in which she sings, “You probably think this song is about you.” Another is Steely Dan’s “Deacon Blues,” when Donald Fagen sings, “I cried when I wrote this song/Sue me if I play too long.” My favorite illustration, though, is probably Neil Young’s “Borrowed Tune,” from Tonight’s the Night:

In the 60s self-reflexivity was often employed as a form of culture jamming, the act of defamiliarizing signs and slogans in order to disrupt habitual, or largely uncritical, patterns of perception and consumption. A famous example of culture jamming from the era is Abbie Hoffman’s Steal This Book, published in 1971 (pictured), which, ironically, sold extremely well, primarily because much of the book offered advice on how to survive with little or no money. There have been entire albums created based on the principle of culture jamming; one of the most singular is The Residents’ The Third Reich 'N' Roll (1976), consisting of defamiliarized versions of Top 40 radio hits of the 1960s. Not all self-reflexive pop songs have such a radical agenda, of course, but all have the effect of disrupting the usual, that is, habitual, patterns of communication.

A Self-Reflexive Play List:

Edward Bear – Last Song

Elton John – Your Song

David Allan Coe – You Never Even Called Me By My Name

Arlo Guthrie – Alice’s Restaurant

Pink Floyd – Mother

Public Image Ltd. – This Is Not A Love Song

Carly Simon – You’re So Vain

Steely Dan – Deacon Blues

James Taylor – Fire and Rain

The Who – Gettin’ In Tune

“Weird Al” Yankovic – Smells Like Nirvana

Neil Young – Borrowed Tune

Saturday, April 17, 2010

Pop Guns

Blame It On Cain:

Aerosmith – Janie’s Got A Gun

Black Velvet Flag – I Shot JFK

Johnny Cash – Folsom Prison Blues

Steve Earle – The Devil’s Right Hand

Bobby Fuller Four – I Fought The Law

Pat Hare – I’m Gonna Murder My Baby

The Jimi Hendrix Experience – Hey Joe

The Kingston Trio – Tom Dooley

The Louvin Brothers – Knoxville Girl

Nas – I Gave You Power

Gene Pitney – The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

Kenny Rogers and The First Edition – Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love To Town

The Rolling Stones – Midnight Rambler

Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska

The Wailers – I Shot the Sheriff

Hank Williams, Jr. – I’ve Got Rights

Neil Young – Down by the River

Friday, April 16, 2010

Wind and Wuthering

In pre-literate, oral civilizations, people experienced their thoughts not as coming from within themselves, but from outside, as Spirit. A thought seemed to come from the gods, or a tree, or a bird, that is, from the outside. Literacy, however, transformed the nature of the subject. To the literate mind, the experience of Self is the experience of interiority: Spirit resides within, as Psyche. In literate experience, therefore, thought originates from inside. Of course, as a consequence of literacy, there was a huge reduction in our relationship with Nature, but for the Romantics, we also won a kind of liberty, the virtue of self-reflection that came with being a discrete self. In order to renew their relationship with Nature, Coleridge and the other Romantics sought to recreate the experience of orality, conveyed by the image of the Aeolian harp, a common household instrument before and during the Romantic Era. (By way of analogy, think of the wind chime.) Just as the harp depends upon the wind for its sound, so, too, does the (passive) poet depend upon the wind for poetic inspiration, as expressed, for instance, in Shelley's “Ode to the West Wind.” Having become strongly associated with the activity of the creative mind, Ralph Waldo Emerson also used the Aeolian harp as a metaphor for the mind of the (Romantic) poet.

In pre-literate, oral civilizations, people experienced their thoughts not as coming from within themselves, but from outside, as Spirit. A thought seemed to come from the gods, or a tree, or a bird, that is, from the outside. Literacy, however, transformed the nature of the subject. To the literate mind, the experience of Self is the experience of interiority: Spirit resides within, as Psyche. In literate experience, therefore, thought originates from inside. Of course, as a consequence of literacy, there was a huge reduction in our relationship with Nature, but for the Romantics, we also won a kind of liberty, the virtue of self-reflection that came with being a discrete self. In order to renew their relationship with Nature, Coleridge and the other Romantics sought to recreate the experience of orality, conveyed by the image of the Aeolian harp, a common household instrument before and during the Romantic Era. (By way of analogy, think of the wind chime.) Just as the harp depends upon the wind for its sound, so, too, does the (passive) poet depend upon the wind for poetic inspiration, as expressed, for instance, in Shelley's “Ode to the West Wind.” Having become strongly associated with the activity of the creative mind, Ralph Waldo Emerson also used the Aeolian harp as a metaphor for the mind of the (Romantic) poet.

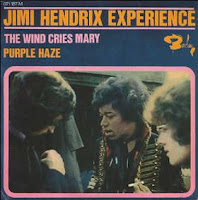

Through the principle of contiguity (metonymy), a thing can be referred to not by its name but by the name of something associated with it. I can say, “Let’s stand in the shade,” but I may be actually saying, “Let’s stand under the leafy branches of that tree over there.” Wind and sand have come to be associated in such a manner, represented by the image of the sand dune, sculpted by the wind. Because wind and sand are interchangeable, and sand is a conventional image for Time (think: hourglass), a phrase such as “dust in the wind” actually refers to power of Time to erase everything one knows, including the trace of one’s own existence. Wind is a constant reminder of one’s mortality. The figurative phrase, “wind of change,” thus names the ineluctable activity of Time. Hence when Jimi Hendrix sings of the wind in his meditation on fame and mortality, “The Wind Cries Mary,” he’s actually reflecting on his own historical significance:

Substitute “my name” for “the names it has blown in the past,” and the point seems clear enough. For a recent song that attempts to reestablish the link between wind and Spirit, listen to “Colors of the Wind,” from the Pocahontas soundtrack.

The Association – Windy

The Byrds – Hickory Wind

Bob Dylan – Blowin’ in the Wind

Patsy Cline – Wayward Wind

Julee Cruise – Slow Hot Wind

Donovan – Catch the Wind

Elton John – Candle in the Wind

England Dan & John Ford Coley – I’d Really Love to See You Tonight

Jethro Tull – Cold Wind to Valhalla

Jimi Hendrix – The Wind Cries Mary

Kansas – Dust in the Wind

Judy Kuhn – Colors of the Wind (Pocahontas Original Soundtrack)

Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band – Against the Wind

Frank Sinatra – Summer Wind

Traffic – Walking in the Wind

Thursday, April 15, 2010

Punk Muse

I came across an interesting comment by Nick Tosches in Gene Gregorits’ fine book, Midnight Mavericks: Reports From the Underground (FAB Press, 2007), which I began reading today. During an interview, Gregorits asked Tosches if he were “the first to coin the term ‘punk rock’?” Tosches replied:

I came across an interesting comment by Nick Tosches in Gene Gregorits’ fine book, Midnight Mavericks: Reports From the Underground (FAB Press, 2007), which I began reading today. During an interview, Gregorits asked Tosches if he were “the first to coin the term ‘punk rock’?” Tosches replied:

Maybe I did coin that term, or at least the “punk” part of it, without knowing it. I don’t know. I wrote a long piece called “The Punk Muse” for a rag called Fusion in 1970. The title referred to the spirit of rock ‘n’ roll in general, not to what later become known as punk rock. (318)

So what does Tosches mean, exactly, by the “punk” spirit of rock ‘n’ roll? Perhaps the answer can be found in Tosches’ own Country: The Twisted Roots of Rock ‘n’ Roll. He writes:

There was an affinity between rockabilly and black music of the 1940s and ‘50s, as there had been an affinity between Western swing and black music of the 1920s and ‘30s. But it was not, really, more than an affinity. Of the sixteen known titles Elvis recorded as a Sun artist, five were derived from R&B records…. What made rockabilly such a drastically new music was its spirit [my emphasis], a thing that bordered on mania. Elvis’s ‘Good Rockin’ Tonight’ was not merely a party song, but an invitation to a holocaust…. Rockabilly was the face of Dionysus, full of febrile sexuality and senselessness; it flushed the skin of new housewives and made pink teenage boys reinvent themselves as flaming creatures. (58-59).

Thus the academic discourse on rock often resembles the early academic discourse on jazz. Belgian critic Robert Goffin, in his early work on American jazz, titled Jazz: From the Congo to the Metropolitan (1944), said of Louis Armstrong, for instance, “[he] is a full-blooded Negro. He brought the directness and spontaneity of his race to jazz music” (167). Goffin was the first to formulate the stereotype which lingers with jazz even now, the stereotype, according to Ted Gioia, “which views jazz as a music charged with emotion but largely devoid of intellectual content, and which sees the jazz musician as the inarticulate and unsophisticated practitioner of an art which he himself scarcely understands” (The Imperfect Art, 30-31). Gioia calls this “the primitivist myth,” a stereotype that rests upon a belief in the primitive’s unreflective and instinctive relationship with his art. Lest one think the primitivist myth is exclusively European, I should point out that the association of jazz and primitivism was uncritically accepted by American jazz critics once the works of the first European critics reached American shores. Few insightful works were written by Americans in the early years of jazz, primarily because it was generally perceived—as was rock ‘n’ roll during the early stage of its popularization by Elvis—as both passing fad and as the musical form of a “decadent” race.

Sunday, April 11, 2010

7 And 7 Is

Long before the rise of Christianity, the cycle of the moon was associated with fertility and goddess worship. Our word moon is a remote cognate of the Latin mensis, for month. Mensis is also the root of the word menstrual, as in the female menstrual cycle. The four quarters of the moon (first, new, third, and full) each consist of seven days, the number seven in the book of Genesis representing the process of creation. Significantly, the seven-sided shape is the only one that cannot be constructed out of a mother circle, and hence is considered the “virgin” number because it can never be “born” as other shapes. Nature refuses to employ the physical structure of seven because it is inefficient, in contrast to the hexagon, a very efficient structure found, for instance, in honeycombs, snowflakes, and in human-made objects such as faucet handles and buckyballs. There are seven colors in a rainbow, Seven Wonders of the World, and the Pleiades were the seven daughters of Atlas. There are seven continents and seven seas, the diatonic musical scale has seven tones, and in many world religions seven is a holy number. In Roman mythology, Diana was known as the virgin goddess, looking after virgins and women, and in some accounts, perhaps not surprisingly, she is the goddess of the moon. Interestingly, in the ancient world the Temple of Diana was long known by its reputation as one of the Seven Wonders of the World. In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, the beautiful Rosaline is sworn to chastity, and is said to have “Dian’s wit.” When Romeo says, famously, “It is the East, and Juliet is the sun. Arise fair sun, and kill the envious moon,” he’s praising Juliet’s decision to spend the night with him and hence surrender her virginity, while also condemning Rosaline’s decision to remain chaste. Unlike Diana, the goddess Venus, the Roman equivalent of the Greek goddess Aphrodite, was associated with love and fertility, and was widely worshiped in Roman religious festivals. Christianity supposedly suppressed Venus worship, although she remains a durable goddess in our popular music.

Long before the rise of Christianity, the cycle of the moon was associated with fertility and goddess worship. Our word moon is a remote cognate of the Latin mensis, for month. Mensis is also the root of the word menstrual, as in the female menstrual cycle. The four quarters of the moon (first, new, third, and full) each consist of seven days, the number seven in the book of Genesis representing the process of creation. Significantly, the seven-sided shape is the only one that cannot be constructed out of a mother circle, and hence is considered the “virgin” number because it can never be “born” as other shapes. Nature refuses to employ the physical structure of seven because it is inefficient, in contrast to the hexagon, a very efficient structure found, for instance, in honeycombs, snowflakes, and in human-made objects such as faucet handles and buckyballs. There are seven colors in a rainbow, Seven Wonders of the World, and the Pleiades were the seven daughters of Atlas. There are seven continents and seven seas, the diatonic musical scale has seven tones, and in many world religions seven is a holy number. In Roman mythology, Diana was known as the virgin goddess, looking after virgins and women, and in some accounts, perhaps not surprisingly, she is the goddess of the moon. Interestingly, in the ancient world the Temple of Diana was long known by its reputation as one of the Seven Wonders of the World. In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, the beautiful Rosaline is sworn to chastity, and is said to have “Dian’s wit.” When Romeo says, famously, “It is the East, and Juliet is the sun. Arise fair sun, and kill the envious moon,” he’s praising Juliet’s decision to spend the night with him and hence surrender her virginity, while also condemning Rosaline’s decision to remain chaste. Unlike Diana, the goddess Venus, the Roman equivalent of the Greek goddess Aphrodite, was associated with love and fertility, and was widely worshiped in Roman religious festivals. Christianity supposedly suppressed Venus worship, although she remains a durable goddess in our popular music.

A Few Venusian Anthems, And Other Goddess Worship:

Frankie Avalon – Venus

Ash - Aphrodite

Jimmy Clanton – Venus In Blue Jeans

Cream – Tales of Brave Ulysses

Miles Davis – Venus de Milo

Fleetwood Mac – Rhiannon

Mike Oldfield – Hymn To Diana

The Shocking Blue – Venus

The Velvet Underground & Nico – Venus In Furs

Wings – Venus And Mars