No critic, of course, can see beyond the curtain of Time. Time is the ultimate critic, and the critic’s limited perspective doesn’t allow him to see beyond his own pitifully narrow moment in history. Critical overcomprehension—the act of giving every new movie an equally glowing reception—is a result of the critic’s deep fear that history may prove him wrong. No one wants to be, for instance, television critic Jack Gould, who reviewed The Milton Berle Show appearance of Elvis Presley for the New York Times in 1956:

Mr. Presley has no discernible singing ability. His specialty is rhythm songs which he renders in an undistinguished whine; his phrasing, if it can be called that, consists of the stereotyped variations that go with a beginner's aria in a bathtub. For the ear, he is an unutterable bore, not nearly so talented as Frank Sinatra back in the latter's rather hysterical days at the Paramount Theater. (qtd. in Robert Ray, 80)

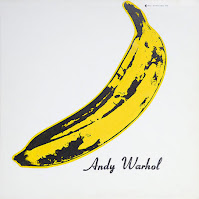

However, as Ray points out, Gould’s kind of critical misjudgment has its own unintended consequences: such gross critical mistakes have led to “rejection and incomprehensibility as promises of ultimate value” (82). For instance, if a record album sold poorly, or the artist who recorded it was given little or no attention—or worse, completely neglected in his or her own time, the record must therefore be great, perhaps even a masterwork. The initial neglect of 1967’s The Velvet Underground & Nico serves as a useful example. Ignored upon release, it is now considered a classic. Initial neglect as a sign of greatness is a powerful myth and governs much of modern criticism of the arts.

According to Self-Styled Siren (critic and film historian Farran Smith Nehme), whose knowledge of silent era Hollywood is nothing short of encyclopedic, the practice of critical overcomprehension is currently being applied to Babylon (2022), a box-office failure upon release last year that also divided critics (“Bye, bye Babylon,” August 23, 2023). While the Siren believes it is a “lousy movie,” nonetheless she has noticed that there are “ongoing attempts to enshrine last year's Babylon as some kind of masterwork,” which is to say, for some, the movie's initial rejection is a surefire guarantee of its ultimate value. The myth serves to shield such movies from negative reviews.

In addition, the Siren refers to a recent New York Times article about the new phenomenon of “MovieTok” influencers. The Times calls them “the new school of film critic,” observing that “some tenets of the profession—such as rendering judgments or making claims that go beyond one’s personal taste—are now considered antiquated and objectionable.” Critics of the new school are never going to make an egregious mistake like Jack Gould made with Elvis Presley. More than that, by insisting that the tenets of a previous generation of critics have become antiquated—meaning they are too old to get what’s really going on—the new school of film critics seeks to shield itself, not simply certain films, but from criticism as well. The new school influencers have little concern for the movie itself. Instead, they are far more interested in the multiple ways they can attribute significance to the movie, e.g., “outrageous,” “extravagant,” “over the top,” “mind-blowing,” “thought-provoking,” on and on. Criticism is simply a form of publicity, and the film itself a commodity.