A few weeks ago I began to explore the mondegreen, the unintentional mishearing of a verbal utterance enabled by homophonic ambiguity. The first venture, "Dead Ants Are My Friends, A-Blowin’ in the Wind," was followed by a second entry, "Betty and the Jets." The third, which I wrote on Easter Sunday exploring the implications of the Biblical mondegreen, I titled "Melon Calling Baby." I have said throughout my discussions of the mondegreen that I'm not so much interested in it as a form of "error" as I am in the way it is a sort of creative interaction with the song's actual lyrics. In my “Betty and the Jets” entry, I’d suggested the existence of the mondegreen, at least insofar as lyrics are concerned, is a consequence of a message being deformed once it is subject to electronic transmission, a technology which emphasizes the received nature of messages.

A few weeks ago I began to explore the mondegreen, the unintentional mishearing of a verbal utterance enabled by homophonic ambiguity. The first venture, "Dead Ants Are My Friends, A-Blowin’ in the Wind," was followed by a second entry, "Betty and the Jets." The third, which I wrote on Easter Sunday exploring the implications of the Biblical mondegreen, I titled "Melon Calling Baby." I have said throughout my discussions of the mondegreen that I'm not so much interested in it as a form of "error" as I am in the way it is a sort of creative interaction with the song's actual lyrics. In my “Betty and the Jets” entry, I’d suggested the existence of the mondegreen, at least insofar as lyrics are concerned, is a consequence of a message being deformed once it is subject to electronic transmission, a technology which emphasizes the received nature of messages.

If information available on the web is correct, then the origin of John Fred (pictured) & His Playboy Band’s marvelous #1 hit of early 1968, “Judy in Disguise (With Glasses),” was the result of John Fred's (actual name: John Fred Gourrier) mishearing The Beatles' lyric, "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds," as "Lucy in Disguise with Diamonds." Hence, “Judy in Disguise (With Glasses)” is one song, at least, that we can definitively point to as a song actually invented or created through mondegreen deformation. The relationship between the two songs is rather obvious, with "Judy in Disguise (With Glasses)" being a pastiche of the earlier tune. There is a match between the bi-syllabic names Lucy/Judy, in which the glyph "L" of Lucy is turned around in mirror-image form to become a "J" (as in "John"), while the phoneme "d" in Judy (and also "Fred") nicely alliterates with the "d" in disguise, just as the "-cy" of Lucy alliterates with the "s" phoneme of “sky.” Additionally, "With Glasses" is a sort of deliberate devaluation of "With Diamonds" (glass being a sort of cheap imitation of a diamond).

Many websites are available that contain the lyrics to "Judy in Disguise (With Glasses)," but I'll present the following lyrics as being a faithful transcription--with one exception, clearly indicated. Highlighted words or phrases are glossed below:

Judy in disguise, well that’s what you are

Lemonade pies with your brand new car

So cantaloupe eyes come to me tonight

Judy in disguise with glasses

Keep wearin’ your bracelets, and your new Rara

And cross your heart, yeah, with your livin’ bra

A chimney sweep sparrow with guise [guys?]

Judy in disguise with glasses

Come to me tonight

Come to me tonight

Taking everything in sight

Except for the strings on my kite

Judy in disguise, hey that’s what you are

Lemonade pies, you got your brand new car

So cantaloupe eyes come to me tonight

Judy in disguise with glasses

Come to me tonight

Come to me tonight

Taking everything in sight

Except for the strings on my kite

Judy in disguise, what you aiming for

A circus of horror, yeah yeah,

Well that’s what you are,

You made me a life of ashes

I…guess…I'll…just…take…your…glasses

Lemonade Pies: At the very least, this phrase is a pastiche of "marmalade skies" of "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" (LSD), although the phrase may be a reference to the sheer size of Lucy's stylish (and presumably yellow) sunglasses, possibly large hooped (yellow) earrings, or perhaps even the characteristic color of her clothing.  An inevitable association, I'm somewhat hesitant to mention, is the word "Pie" with female genitalia. The slang phrase, "Hair Pie" (cf. Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band's Trout Mask Replica), is a slang term for female genitalia that one may "eat," that is, perform oral sex. The meaning of "lemonade" given the terms of this reading hardly needs to be made explicit.

An inevitable association, I'm somewhat hesitant to mention, is the word "Pie" with female genitalia. The slang phrase, "Hair Pie" (cf. Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band's Trout Mask Replica), is a slang term for female genitalia that one may "eat," that is, perform oral sex. The meaning of "lemonade" given the terms of this reading hardly needs to be made explicit.

Cantaloupe eyes: Again, a pastiche, this time of of the collocation "kaleidoscope eyes" of LSD. The word kaleidoscope is derived from the Greek words kalos, meaning beautiful, and eidos, meaning form, and hence does not refer to colors as such, although the child's toy referred to as a "kaleidoscope" often produces startling color combinations. Actually, the word "kaleidoscope" refers to the shifting colored shapes one can see at the end of the scope, not the colors themselves. "Cantaloupe eyes" therefore seems to be a surreal metaphor at its farthest reach, but in any case refers to the shape of her eyes (or perhaps her glasses) and not their color.

Your new Rara: "Rara" is a reference to a chic brand of women's clothing, particularly a stylish kind of sexy dress. Hence "new Rara" reiterates the "new car" of the previous stanza, suggesting the vast disposable income of the femme fatale's parents. The implication is that she is spoiled and pampered, like the "rich bitch girl" in Hall and Oates' "Rich Girl" ("You can rely on the old man's money").

Cross your heart, yeah, with your livin' bra: A reference to the "Playtex Living Bra," that is, a brand of brassiere introduced in the mid-60s employing an innovative "cross your heart" means of breast support (as the adman's slogan went), meaning a brassiere that could provide more comfortable and more shapely support. In 1968 this particular lyric was quite provocative, although it may be hard to believe now. My wife Becky and I both remember the "livin' bra" lyric to be the subject of sensational conversation when we (at the time) were still in junior high. As my friend Tim Lucas pointed out to me, John Fred ventured into territory with this lyric that The Beatles wouldn't tackle until "Ob La Di, Ob La Da" ("Life goes on...bra!") in late 1968. "Burn your bra," was a feminist slogan in the 1960s, the symbolic casting off of middle-class, bourgeoisie repression. Our femme fatale is not a feminist.

Chimney sweep sparrow with guise: Most sites containing the lyrics to this song have the word "guise"--but is it actually the homophone of "guise," guys? For me, this is probably the most elusive line in the entire song. If the word is "guise," then to what does the metaphorical phrase, "Chimney sweep sparrow," refer? But if the word is "guys," then the lyric is more intelligible, the swift, swooping, darting flight of a chimney sweep sparrow being the key image. "Chimney sweep sparrow with guys" would then be descriptive of her behavior, flitting from one "guy" (boy) to the next, the repetitive behavior of our femme fatale to "seduce and abandon" the boys who fall under her spell. She engages in "serial dating," but is loyal to no one boy--"guy." Mary Wells, in "My Guy," sings, "I'm stickin' to my guy like a stamp to letter/Like birds of a feather we stick together." Not so of our "Judy in disguise."

Except for the strings on my kite: Perhaps an oblique reference to The Beatles song, "Being For the Benefit of Mr. Kite" from Sgt. Pepper's. It seems more likely, however, that "the strings on my kite" is a metaphor for male sexual arousal, the erection our narrator has whenever he's near our femme fatale. Thus the utterance, "Taking everything in sight/Except the strings on my kite," means she's quite willing to "make out," indeed, is quite aggressive when doing so, but refuses to "put out," or engage in sex. Hence our narrator is turned on by her behavior, but complains of the lack of sexual fulfillment, of consummation. In other words, she's a "tease."

What you aiming for: Our narrator's admission that he's suspicious of her motives, that is, is fundamentally afraid of her. That she's a mystery to him is suggested by her (sun)glasses which disguise her, not her appearance, but what she actually desires "in her heart."

Circus of horror: Circus of Horrors was a British film released in 1960, a loose adaptation of Phantom of the Opera set within a circus. Interestingly, several of its characters figuratively wear masks: either disfigured or seeking a disguise, their visages are restored and/or modified by reconstructive surgery. Additionally, the film featured prominently the pop song Look for a Star on its soundtrack. The lyric, "A circus of horror...is what you are," is actually the most explicit lyric in the entire song in terms of its characterization of the femme fatale: she may be beautiful in appearance, but in reality she is a monster, hiding her real nature by means of her disguise.

You made me a life of ashes: The goal of the femme fatale may or may not be conscious, but in any case she initiates a series events that result in the complete destruction of the male--not his death, but the complete destruction of his world.  Her objective is not to destroy him, but rather his world, to initiate in the male a crisis of subjectivity, the ontological destruction of everything he believed to be certain. Hence the appropriateness of the metaphor, "life of ashes." While I cannot "prove" it--nor do I have any inclination to do so--I choose to believe that John Fred had in mind the famous image of Sue Lyon from Stanley Kubrick's Lolita (1962), which seems to me an image which sufficiently captures the femme fatale he was trying, impressionistically, to sketch.

Her objective is not to destroy him, but rather his world, to initiate in the male a crisis of subjectivity, the ontological destruction of everything he believed to be certain. Hence the appropriateness of the metaphor, "life of ashes." While I cannot "prove" it--nor do I have any inclination to do so--I choose to believe that John Fred had in mind the famous image of Sue Lyon from Stanley Kubrick's Lolita (1962), which seems to me an image which sufficiently captures the femme fatale he was trying, impressionistically, to sketch.

One final remark: "Judy in Disguise (With Glasses)" is referred to by some as "bubblegum," but I think this incorrect. Prior to recording the song, John Fred had worked with several prominent New Orleans musicians, including members of Fats Domino's band and Mac Rebennack (Dr. John). I agree with those who see the song as R&B with psychedelic features; its overt allusion to "Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds" also recommends it as an example of psychedelia.

Exergue: For those interested, "Judy in Disguise (With Glasses)" is one of the mid-60s Top 40 songs "covered" (as it were) on the Residents' album "The Third Reich 'n' Roll," apparently because the Residents were from Louisiana, as was John Fred.

Saturday, April 19, 2008

Mondegreen, Pt. 4: Lucy in Disguise With Diamonds

Friday, April 18, 2008

Whistle While You Read

Whistle [OE. hwistle] An act of whistling; a clear shrill sound produced by forcing the breath through the narrow opening made by contracting the lips; esp. as a call or signal to a person or animal; also as an expression of surprise or astonishment; rarely, the action of whistling a tune. [OED]

Whistle [OE. hwistle] An act of whistling; a clear shrill sound produced by forcing the breath through the narrow opening made by contracting the lips; esp. as a call or signal to a person or animal; also as an expression of surprise or astonishment; rarely, the action of whistling a tune. [OED]

TCM's screening a few months ago of several films in Columbia's Whistler series (eight films 1944-48, seven of them starring Richard Dix) prompted me to think about how whistling is used in movies and in music, the way it is employed and what it signifies when it is used. I've always very much enjoyed the Whistler series--several installments of which, incidentally, were directed by William Castle. The Whistler began as a CBS radio series in 1942 and ran until 1955 (during which time, additionally, were made the eight films mentioned above). Each episode began with the haunting opening theme--whistled, of course--while the slightly sinister narrator introduced himself, saying to the listener, "I am the Whistler and I know many things, for I walk by night. I know many strange tales hidden in the hearts of men and women who have stepped into the shadows. Yes, I know the nameless terrors of which they dare not speak."

The god-like omniscience of the Whistler has always vaguely suggested to me the mechanism of Fate or Destiny itself, since He (the voice was male) knows the secret desires (what is "hidden in the hearts") of men and women, what obsessive, overwhelming desire drives them and has distorted or deformed them--and hence will destroy them ("character is fate"). Although I haven't researched this topic in depth, the figure of the Whistler is most likely distantly related to the figure of the Pied Piper (a pipe is form of whistle), the mysterious musician dressed in many colors whose piping hypnotically lures the children of Hameln off to their doom (the Grimm Brothers' version). It is this association we have with whistling that Peter Gabriel, for instance, invokes in "Intruder" (Peter Gabriel, 1980).

In movies whistling is often associated with surprise (just about every World War II movie) but also a signal of attraction, a culturally symbolic gesture made by an American male to proclaim (without the use of speech) his approval, erotically speaking, of a particular dame. In music, whistling can also signify contentment or happiness ("Don't Worry, Be Happy"), solitary, melancholy contemplation ("(Sittin' on) The Dock of the Bay"), self-absorbed autoeroticism ("Centerfold"), pleasant, relaxing idleness ("I Love to Whistle"; also, the theme from The Andy Griffith Show), or even merely a way to pass the time, to avoid monotony when speech is either impossible or forbidden ("Colonel Bogey March"; "Whistle While You Work" from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs), but it is always is associated with a solitary individual alone with his thoughts, even if that individual is within a crowd. A popular "crooner" such as Bing Crosby frequently whistled in his songs, an act often signifying self-contentment but also an unrestrained joie de vivre.

Ten Representative Recordings Featuring Whistling:

“Colonel Bogey March”—A song popularized by British soldiers during World War I. In the game of golf, a “bogey” is, of course, a designation for being one stroke over par. Legend has it that the tune was inspired by two golfers, known to the song’s composer, who preferred to whistle two descending notes rather than shouting “Fore!” Although written in 1914, “Colonel Bogey March” later became, famously, the theme song to the highly successful World War II movie, The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). Widely known as an avid golfer, Bing Crosby may have been inspired to adopt his frequent practice of whistling because of this song (long before the 1957 film, of course).

The Bangles, “Walk Like an Egyptian”

Bobby Bloom, “Montego Bay”

Bing Crosby, “Moonlight Becomes You”

Peter Gabriel, “Intruder”

Peter Gabriel, “Games Without Frontiers”

J. Geils Band, “Centerfold”

Kay Kyser and His Orchestra, “I Love to Whistle” (Sully Mason, vocal)

Bobby McFerrin, “Don’t Worry, Be Happy”

Otis Redding, "(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay"

Virtually all of these songs were huge hits, incidentally. Is the fact that they all contain whistling simply coincidental, or do most people enjoy songs with whistling as much as I do?

Wednesday, April 16, 2008

Hazel Court, 1926-2008

The sad news arrived yesterday that British actress Hazel Court died at age 82. I never met her, although she was very supportive of my and David's forthcoming book on the Roger Corman Poe Cycle (1960-64), Nevermore (link is on the right), to be published by Tomahawk Press. Indeed, Hazel's own autobiography is forthcoming--very soon--from Tomahawk Press, and it saddens me that she never lived to see it in print. Hazel had expressed great interest to David about our Nevermore book, and had agreed to read the relevant chapters on the films in which she had appeared and contribute additional relevant information to our discussion. Sadly, that will never happen, but it only reaffirms the urgency with which David and I must complete the work, as many of the surviving individuals involved in the Poe films are also in their 80s. An overview of Hazel's career can be found here, while Tim Lucas wrote a brief eulogy that I found quite touching.

The sad news arrived yesterday that British actress Hazel Court died at age 82. I never met her, although she was very supportive of my and David's forthcoming book on the Roger Corman Poe Cycle (1960-64), Nevermore (link is on the right), to be published by Tomahawk Press. Indeed, Hazel's own autobiography is forthcoming--very soon--from Tomahawk Press, and it saddens me that she never lived to see it in print. Hazel had expressed great interest to David about our Nevermore book, and had agreed to read the relevant chapters on the films in which she had appeared and contribute additional relevant information to our discussion. Sadly, that will never happen, but it only reaffirms the urgency with which David and I must complete the work, as many of the surviving individuals involved in the Poe films are also in their 80s. An overview of Hazel's career can be found here, while Tim Lucas wrote a brief eulogy that I found quite touching.

Monday, April 14, 2008

Making Cottage Cheese Out of the Air

You never know what’s going to turn up at a Goodwill Store. While running a few quick errands late yesterday morning I thought I’d stop by and check out the Goodwill store’s music bins, a weekly habit of mine (more or less) for the past several years, just to see if by chance anything interesting might have shown up since the last time I visited. While browsing through the vinyl records—an antiquated form of musical storage in this digital age, most always in terrible shape and not worth buying, even for the price of $1—I happened across a well-preserved copy of the soundtrack to the AIP release Hell’s Angels ’69 (Capitol Records) actually autographed on the front cover by Sonny Barger, at the time of the film head of the Oakland chapter of the Hell’s Angels and later a key player in the Rolling Stones’ infamous concert at Altamont Speedway in December 1969.

You never know what’s going to turn up at a Goodwill Store. While running a few quick errands late yesterday morning I thought I’d stop by and check out the Goodwill store’s music bins, a weekly habit of mine (more or less) for the past several years, just to see if by chance anything interesting might have shown up since the last time I visited. While browsing through the vinyl records—an antiquated form of musical storage in this digital age, most always in terrible shape and not worth buying, even for the price of $1—I happened across a well-preserved copy of the soundtrack to the AIP release Hell’s Angels ’69 (Capitol Records) actually autographed on the front cover by Sonny Barger, at the time of the film head of the Oakland chapter of the Hell’s Angels and later a key player in the Rolling Stones’ infamous concert at Altamont Speedway in December 1969.

I’ve never seen Hell’s Angels ‘69, although I’ve read a few on-line reviews of Media Blasters’ 2004 DVD release of the film (none of which compelled me to purchase the DVD). Having listened, now, to the soundtrack (about 28 minutes or so in length), I’m still not inclined to see the film, although as a result of the inevitable process of mental association, I began thinking about so-called “biker music” and, consequently, the band Blue Cheer (initially formed by Bruce Stephens, Dickie Peterson, and Paul Whaley).

Certainly Blue Cheer--perhaps best known for its riotous metal version of Eddie Cochran’s “Summertime Blues,” a Top 20 hit in 1968--has to be considered the biker band, not necessarily because they played louder than everybody else (although the band’s volume is legendary), but because early on, at least, their manager was a Hell’s Angel nicknamed “Gut,” mentioned several times throughout Hunter S. Thompson’s book, Hell’s Angels (1966):

At that time [1965], Gut was not technically a Hell’s Angel. Several years earlier he had been one of the charter members of the Sacramento chapter—which like the Frisco chapter, began with a distinctly bohemian flavor. (127)

Thompson also notes that Gut had completed a year of junior college and “wanted to be a commercial artist.” Apparently he got the chance by hooking up with Blue Cheer sometime in 1967. He received co-credit for the artwork of Blue Cheer’s first album, Vincebus Eruptum (1968, pictured above), along with John Van Hamersveld (Van Hamersveld took the cover photograph, but the now famous cover design is Gut’s). Gut is also credited with the LP album cover design (not cover painting) for Blue Cheer’s second album, Outsideinside (1968), which opens into an “L” shape when fully unfolded. He is not explicitly connected with any album artwork on the third or subsequent albums, so I assume by that time his relationship with the band had ended. (The group itself subsequently disbanded around 1971, but re-formed in the late 1980s.) Gut is also credited with some producing some poster art in connection with Blue Cheer concerts as well.

Donald Clarke’s The Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music (Penguin paperback, 1990), contains a quotation by Gut that I’m compelled to reproduce here.  Gut said of Blue Cheer: "They play so hard and heavy they make cottage cheese out of the air" (124). I take this as a psychedelicized form of compliment, but clearly Blue Cheer’s appeal was more than the fact that they simply played loud. Although the band members had hippie credentials--the band was supposedly named in homage to a form of LSD, plus they had long hair, bell bottoms, in short, all the appropriate attire--the association of Blue Cheer with “biker music” has to have its origins in that curious, improbable relationship the Hell's Angels had with the hippie counterculture. In his autobiography, Hell's Angel, Sonny Barger says that "The sixties were the best thing that ever happened to the Hell's Angels" (p. 130). The Hell's Angels liked hippies (in contrast to Berkeley radicals), he says, because it was understood that women were always to be the means of exchange: he claims that a hippie would let him screw his girlfriend in return for a ride on his motorcycle (130). Moreover, some members of the Hell's Angels, such as Gut, weaved their lives "into the hippie scene." Certainly both groups saw themselves in the broadest sense as rebels, and both groups saw themselves as unsuited to the demands of a conventional, middle-class life, and held deep disdain for genteel, bourgeoisie sexual morality. Interviewed in 2006, Dickie Peterson tends to confirm what Sonny Barger wrote in his autobiography:

Gut said of Blue Cheer: "They play so hard and heavy they make cottage cheese out of the air" (124). I take this as a psychedelicized form of compliment, but clearly Blue Cheer’s appeal was more than the fact that they simply played loud. Although the band members had hippie credentials--the band was supposedly named in homage to a form of LSD, plus they had long hair, bell bottoms, in short, all the appropriate attire--the association of Blue Cheer with “biker music” has to have its origins in that curious, improbable relationship the Hell's Angels had with the hippie counterculture. In his autobiography, Hell's Angel, Sonny Barger says that "The sixties were the best thing that ever happened to the Hell's Angels" (p. 130). The Hell's Angels liked hippies (in contrast to Berkeley radicals), he says, because it was understood that women were always to be the means of exchange: he claims that a hippie would let him screw his girlfriend in return for a ride on his motorcycle (130). Moreover, some members of the Hell's Angels, such as Gut, weaved their lives "into the hippie scene." Certainly both groups saw themselves in the broadest sense as rebels, and both groups saw themselves as unsuited to the demands of a conventional, middle-class life, and held deep disdain for genteel, bourgeoisie sexual morality. Interviewed in 2006, Dickie Peterson tends to confirm what Sonny Barger wrote in his autobiography:

Gut liked our band and came on as our manager. Now through Gut we played a lot of the earlier Hell's Angels parties, along with Big Brother and the Holding Company. There would be Angels coming over to our house, we always had plenty of chicks around and we were always in a party mode, and at the time that's basically what the Angels were. We didn't have a big affiliation with the club, we just knew some of these guys that were friends of Gut's and they would come over to the house and we would party around. These people were all very nice to us, they were the ones that first put me on a Harley. To me it was sort of a childhood dream come true, because when I was growing up in San Francisco sometimes I would cut school to get down to Frederick's street by two o'clock in the afternoon, because these guys would come roaring by on their way out to Playland by the ocean where they hung out at the funhouse. Me and my friends didn't want to miss this, and I wanted to grow up to be like that. So how this all tied in and how it all came together was always a mystery to me, but I'm glad it did. Gut, the Angel that was managing us then, he was a mentor to me.

But how did the music of a power trio serve as the common ground between these groups? Perhaps the lyrics of "Summertime Blues" provide a clue:

I'm gonna raise a fuss, I'm gonna raise a holler

About a-workin' all summer just to try to earn a dollar

Every time I call my baby, and ask to get a date

My boss says, "No dice son, you gotta work late"

Sometimes I wonder what I'm a gonna do

But there ain't no cure for the summertime blues

Well my mom and pop told me, "Son you gotta make some money"

If you want to use the car to go ridin' next Sunday

Well I didn't go to work, told the boss I was sick

"Well you can't use the car 'cause you didn't work a lick"

Sometimes I wonder what I'm a gonna do

But there ain't no cure for the summertime blues

In retrospect, these lyrics suggest a countercultural sensibility avant le lettre, a deep frustration with the prospect of a banal, middle-class existence. But what, precisely, was Blue Cheer's particular innovation? The band made this (by 1968) decade-old song sound new and contemporary; the band brought it "up to date," not simply by covering its lyrics but by altering its sound. The thunderous roar of a heavy metal guitar mimics not only the roar of a Harley-Davidson motorcycle with the exhaust mufflers removed; it also mimics the drone of the factory. It represents not the polished technique of a trained professional, but instead the rough playing of an inspired amateur: it is a blue collar, working class sound, one that is perceived by its listeners as authentic, "hard" as in "hard-working," but equally important, visceral. Regarding Gut's comment about Blue Cheer's sound making "cottage cheese out of the air," Peterson said:

At the time when we first started music was solely an audio sensation that you got with your ears. After standing in front our our amps and feeling the vibration from the speakers, we said, "Wait a minute. This is what people gotta feel, this is what they gotta experience, they gotta experience the air, the wind, the waves hitting them from these speakers. That's what they've gotta experience in order to really experience music." This is what prompted us to keep crankin' it up! That's why he used the term "they turn the air into cottage cheese." Because we would, we would make the air thick with the vibration of those cabinets to where it was quite a physical experience.

Which band took the same approach as Blue Cheer but had far greater success? Grand Funk Railroad. They were also loud, long-haired, sweaty, and shirtless, with a working-class sensibility (We're An American Band"). What happened to Grand Funk once they dropped their metal edge and became more "pop" sounding ("Some Kind of Wonderful")? They were dropped by their constituency, and didn't survive the 1970s, either.

Friday, April 11, 2008

Grease For Peace

Joe Sasfy, who created Time-Life’s 50-album, 1, 100 song, Rock 'n' Roll Era series some years ago, emailed me in connection with my March 13 blog entry, in which I discussed Art Laboe’s Oldies But Goodies series of compilation albums. I’m quite sure that Time-Life’s Rock 'n' Roll Era is the biggest and biggest-selling oldies series of all time.

Joe Sasfy, who created Time-Life’s 50-album, 1, 100 song, Rock 'n' Roll Era series some years ago, emailed me in connection with my March 13 blog entry, in which I discussed Art Laboe’s Oldies But Goodies series of compilation albums. I’m quite sure that Time-Life’s Rock 'n' Roll Era is the biggest and biggest-selling oldies series of all time.

Mr. Sasfy reports that Time-Life has just inked a deal with Art Laboe and will issue a new, 10-CD collection titled The Ultimate Oldies But Goodies Collection, to be sold primarily as an infomercial. The host of the infomercial will be Bowzer (Jon Bauman, pictured) of the group Sha Na Na. Readers are invited to review my earlier blog entry, in which I linked Art Laboe and the Mothers of Invention album Cruising With Ruben & the Jets (1968) to the formation of Sha Na Na in the late 60s, an “oldies” act that very early in its performing history appeared, somewhat improbably, at the Woodstock Festival (August 1969).

Like many people did, I first saw Sha Na Na in Warner Brother’s documentary of the Woodstock Festival, Woodstock (1970), performing "At the Hop." For some reason, although my parents primarily listened to swing music, they always seemed for some reason to have on Sha Na Na’s television variety show (1977-81) at the appropriate time--episodes of which, surprisingly, have never appeared on DVD. During those same years, in 1978, Sha Na Na appeared in the hugely successful motion picture version of the musical Grease, under the name of Johnny Casino and the Gamblers; their songs can be heard on that movie’s very popular soundtrack. The group still performs to this day.

Regarding the Ultimate Oldies But Goodies Collection, Mr. Sasfy says, “You might say that, as we teeter here at the edge of rock ‘n’ roll history, all the remaining players in the oldies 'game' have joined together for one last un-ironic nostalgia fest.” I have written Mr. Sasfy asking him to keep me posted regarding the availability of the forthcoming Ultimate Oldies But Goodies Collection; I will let you know as soon as I hear something.

In the meantime, to quote Bowzer's parting message that closed each Sha Na Na television show: “Grease for Peace!”

Thursday, April 10, 2008

University of Nebraska at Kearney student Grant Campbell responded to an observation I made in my previous (April 9) blog entry, “Rock History and How It’s Made,” prompting me to expand on some comments I made in that post. In response to my previous entry, he made the following comment:

University of Nebraska at Kearney student Grant Campbell responded to an observation I made in my previous (April 9) blog entry, “Rock History and How It’s Made,” prompting me to expand on some comments I made in that post. In response to my previous entry, he made the following comment:

The technology aspect is most certainly a driving force behind the change in “style” of the era’s [the 1960s] music. However, wouldn't it be genealogical for a certain era’s musicians to find their own way of utilizing that technology? I know you aren't taking ALL the credit away from musicians and giving it to technology. But if technology is going to advance anyway, I still think that it is the artists who need to be primarily recognized for their creative genius.

I should add that he’s responding to an observation I made at the end of my post, that most histories of rock ‘n’ roll focus on influence understood rather narrowly as artistic influence, rather than on the influential role of technological innovation, an “invisible” factor driving popular musical change. While I was by no means trying to diminish the role of the musician, I should say that what is meant by “artistry” might well in fact mean, in part, how the musician exploits the potential of a new technology, meaning on that point I'm in agreement with Grant when he talks about a musician’s finding his “own way of utilizing” a specific technology. But I would add that technological changes continue to challenge and modify what we mean by "artist" in the first place.

Since I suspect there are many who share his thoughts (or rather, hesitations), perhaps I ought to provide some examples of what I meant by my earlier assertion about the role of technology in popular music in order to illustrate my general point (not an entirely original one, I might add):

--Frank Sinatra responded to the development of the LP (long-play) record by creating albums unified by a sense of mood or tone, e.g., In the Wee Small Hours (1955). With an entire side available consisting of roughly twenty minutes, he was no longer restricted by the limitations of one side of a 78, or roughly five minutes. The second side of The Beatles’ Abbey Road (1969) exploits the length of a side of the LP in a similar way. Remember that the word “album” used to refer to a heavy cardboard portfolio that consisted of several 78s tucked inside separate sleeves, not a single 12" LP record.

--In the 1960s, rock musicians responded to the potential of the LP by “stretching out” or “jamming”—the “jam session,” which sometimes took up the entire side of an LP. While I certainly don’t wish to get into a simple “chicken-or-egg” dialectical argument, one wonders whether the storage capacity of one side of an LP didn’t in fact prompt musicians to stretch out or jam in the first place. A case in point is a band such as the Grateful Dead, a band that made records attempting to duplicate the ambiance of their live concerts, a practice in flat contradiction to that of most bands at the time, which tried to make their concerts sound like their records.

--The development of multitrack recording, among other engineering innovations, enabled the development of psychedelic music, the aural equivalent of an hallucinogenic trip. As Jim DeRogatis observes:

Musicians couldn’t specifically reproduce any of these [hallucinogenic] sensations, but drug users also talked about a transfigured view of the everyday world and a sense that time was elastic. These feelings could be invoked—onstage [synaesthesia, the “psychedelic light show”] but even more effectively in the recording studio—with circular, mandala-like song structures; sustained or droning melodies; altered and effected instrumental sounds; reverb, echoes, and tape delays that created a sense of space, and layered mixes that rewarded repeated listening by revealing new and mysterious elements. (Turn On Your Mind, Hal Leonard Corporation, 2003, p. 12)

The “altered and effected” instrumental sounds to which DeRogatis refers are technically known as “non-linear synthesis,” meaning that the sound that goes in to a particular electronic device is not the sound that comes out—think, for example, of the use of the Leslie (see my earlier entry) or the ring modulator. In this sense, I suppose, the use of technology to approximate a drug trip is an example of the banal insight that technology follows the path of ideology.

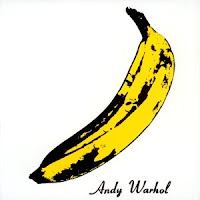

--After a live concert, the Velvet Underground--the band which I specifically mentioned in my last post--frequently left the stage leaving their plugged-in guitars behind, thus enabling a self-sustaining feedback effect (the amplifiers would generate sound waves that in turn would vibrate the guitars' strings, thus creating a loopiness, or self-sustaining feedback). Jimi Hendrix often did the same thing, exploiting electronic technology’s potential to operate independent of any conscious (human) control. Lou Reed's later Metal Machine Music (1975) is an entire album consisting of self-sustained feedback, pushing the point of technology's ability to operate autonomously of human control to the extreme--see below.

--In a further development since the 1960s, digital sampling enables one to make a record by combining fragments of songs compiled entirely from previous recordings—yet another challenge to what is traditionally meant by the word artist. Certainly the Velvet Underground was—in the traditional sense of the word—influenced by Andy Warhol’s notion of the pop artist, since he was at the time the VU formed using found photographs for the making of prints.  Remember that Warhol referred to his studio as the Factory, suggesting the potential for “art” to be a mass-produced item just like any other, or perhaps, no different than any other. Think of Duchamp's "Fountain," a urinal to which he applied the signature "R. Mutt" and placed in an art gallery.

Remember that Warhol referred to his studio as the Factory, suggesting the potential for “art” to be a mass-produced item just like any other, or perhaps, no different than any other. Think of Duchamp's "Fountain," a urinal to which he applied the signature "R. Mutt" and placed in an art gallery.

The larger point, I think, is that the language we use to talk about popular music is itself problematic, for as the practice of digital sampling reveals, terms such as "artist" and "musician" no longer really function. The question we need to consider seriously is whether they were terms antiquated decades ago, when rapid changing technologies began to profoundly change popular music.