For some reason, I awoke this morning thinking about the role of the recording engineer in rock and pop music. The best analogy I can think of to understand the role of the recording engineer is that the engineer is to a record what the cinematographer is to a movie. If the latter makes artifice and theatricality seem “natural,” the recording engineer makes sounds seem “captured,” not created. It is therefore not surprising that the contributions of the recording engineer and the cinematographer are recognized within their professional disciplines by prestigious awards (e.g., the Grammy and Academy Awards). There have been, and are, many revered engineers in the history of popular music, many of them known for their contributions to the success of various groups, for instance, Dave Hassinger (early Rolling Stones), Roger Nichols (Steely Dan), Hugh Padgham (Peter Gabriel, The Police), Alan Parsons (Pink Floyd), and Bill Szymczyk (The James Gang, The Eagles). A lesser-known engineer whose career has always interested me, primarily because of his association with the experimental, avant-garde band Pere Ubu, is Kenneth (Ken) Hamann, who began his career at the Cleveland Recording Company in 1950. According to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History website, Ken Hamann was named the chief engineer of Cleveland Recording Co. in 1956,

For some reason, I awoke this morning thinking about the role of the recording engineer in rock and pop music. The best analogy I can think of to understand the role of the recording engineer is that the engineer is to a record what the cinematographer is to a movie. If the latter makes artifice and theatricality seem “natural,” the recording engineer makes sounds seem “captured,” not created. It is therefore not surprising that the contributions of the recording engineer and the cinematographer are recognized within their professional disciplines by prestigious awards (e.g., the Grammy and Academy Awards). There have been, and are, many revered engineers in the history of popular music, many of them known for their contributions to the success of various groups, for instance, Dave Hassinger (early Rolling Stones), Roger Nichols (Steely Dan), Hugh Padgham (Peter Gabriel, The Police), Alan Parsons (Pink Floyd), and Bill Szymczyk (The James Gang, The Eagles). A lesser-known engineer whose career has always interested me, primarily because of his association with the experimental, avant-garde band Pere Ubu, is Kenneth (Ken) Hamann, who began his career at the Cleveland Recording Company in 1950. According to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History website, Ken Hamann was named the chief engineer of Cleveland Recording Co. in 1956,

and over the next decade, in addition to engineering award-winning remote broadcast recordings of the yearly Bach Festival and Oberlin College Contemporary Music Festivals, helped build the studio into a state-of-the-art recording and mastering facility in which many regional and national hit records were produced. These included the Outsiders’ “Time Won't Let Me,” the Human Beinz’ “Nobody But Me,” the Lemon Pipers’ “Green Tambourine,” and albums by the James Gang and Grand Funk Railroad.

The encyclopedia entry goes on to say that in 1970 Hamann and production engineer John Hansen purchased the Cleveland Recording Co. from original owner Frederick C. Wolf. I discovered that a few years later, in 1977, they sold the company, and Hamann moved to Painesville, where he set up Suma Recording Studio. According to this site, Hamann died in January 2003, but his son Paul Hamann continues the family tradition of engineering and recording as the owner and chief engineer of Suma. While by no means definitive (it’s a work-in-progress), here are a few rock albums engineered by Ken Hamann over the years. The problem with compiling a definitive list is that the engineer wasn’t always acknowledged in an album’s credits, but I have done my best.

Tiffany Shade – Tiffany Shade (1967)

Yer’ Album – The James Gang (with Bill Szymczyk) (1969)

Smooth as Raw Silk – Silk (with Bill Szymczyk) (1969)

On Time – Grand Funk Railroad (1969)

Damnation – The Damnation of Adam Blessing (1969)

Grand Funk – Grand Funk Railroad (1969)

Closer to Home – Grand Funk Railroad (1970)

Bloodrock 2 – Bloodrock (1970) (“D.O.A.”)

Survival – Grand Funk Railroad (1971)

E Pluribus Funk – Grand Funk Railroad (1971)

Live–The 1971 Tour – Grand Funk Railroad (issued 2002)

Thirds – The James Gang (with Bill Szymczyk) (1971)

Mom’s Apple Pie – Mom's Apple Pie (1972)

Bloodrock Live – Bloodrock (1972)

Bang – The James Gang (1973)

Wild Cherry – Wild Cherry (1976) (“Play That Funky Music”)

Jesse Come Home – The James Gang (1976)

For me, though, Ken Hamann’s most interesting work is for the self-proclaimed “avant garage” band from Cleveland, Pere Ubu. I’m not quite sure about Ken Hamann’s age when he began working with Pere Ubu, but I remember reading (or being told by someone) that he was nearing retirement when the band approached him about recording their music. My memory may be incorrect, but this fact seems intuitively correct since he had been in the U. S. Navy during World War II, and hence would have been around sixty years old when he was introduced to the band in 1976—just a few years from retirement. In any case, according to The Hearpen Singles, a box set containing reissues of the first four 7” singles released by Pere Ubu in the 1970s, Ken Hamann engineered all of the band’s first singles except the very first (“30 Seconds Over Tokyo”/”Heart of Darkness”), released in December 1975. The band began recording at Cleveland Recording Co. in February 1976 (“Final Solution” and “Cloud 149”). Hamann is also credited as producer on the single “The Modern Dance”/“Heaven” (1977). He is credited as engineer and co-producer of the band’s first three studio albums as well:

The Modern Dance (1978) (Three songs recorded at Cleveland Recording Co.; the remainder at Suma Recording in Painesville in 1977)

Dub Housing (1978)

New Picnic Time (1979)

For whatever reason (retirement?), he ceased working with Pere Ubu after 1979’s New Picnic Time, but he later engineered Variations On A Theme by David Thomas and the Pedestrians, released in 1983. His son, Paul, engineered all subsequent Pere Ubu albums beginning with The Art of Walking (1980) through Cloudland (1989), and continued to engineer various tracks on subsequent albums thereafter, while also remastering and mixing live tapes from the 1970s and early 1980s for release on CD (e.g., One Man Drives While The Other Man Screams, 1989). Ken Hamann’s contribution to Pere Ubu’s sound is acknowledged by David Thomas in this article from 2006. Moreover, Hamann’s work also inspired one doctoral dissertation. According to this article, Susan Schmidt Horning, who met Hamann in 1968 and marveled at his ability to manipulate sound, was later inspired to investigate the relationship of music and technology in sound recording studios. She authored Chasing Sound: The Culture and Technology of Recording Studios in America, 1877-1977 (Ph.D. dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, 2002), which won the Ohio Academy of History’s 2003 Outstanding Dissertation Award.

Below is a list of books exploring the link between technology and music. If anyone can contribute to my on-going list of records engineered by Ken Hamann, or additional information, please feel free to send me an email.

Additional Readings:

Michael Chanan, Repeated Takes: A Short History of Recording and Its Effects on Music. Verso, 1997.

Mark Katz, Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music. University of California Press, 2004.

David L. Morton, Jr., Sound Recording: The Life Story of a Technology. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Paul Théberge, Any Sound You Can Imagine: Making Music/Consuming Technology. Wesleyan/University Press of New England, 1997.

Saturday, June 27, 2009

Avant Garage

Thursday, June 25, 2009

Jacksonism: Michael Jackson, 1958-2009

I think it was Greil Marcus who observed that Michael Jackson was a god who became a mere celebrity, and there is a terrible truth to this observation. For the last quarter century of his life—that is, the second half—Michael Jackson’s career seemed like nothing so much as an apocalyptic spiral that served as an illustration of the Platonic allegory of the consequences of the inevitable deviation from the Good. He resembles no rock star so much as Elvis, for reasons, I suspect, that will emerge in those inevitable biographies sure to be published, controversial and otherwise, in the coming years. Who shall be to Michael Jackson what Albert Goldman was to Elvis? Jacksonism’s biggest year, arguably, was 1984, the year during which the tidal wave crested and broke, but by then he could claim a world record no one, not even Elvis or the Beatles, had managed to achieve: he had made one monumental, colossal LP—THRILLER, produced by Quincy Jones—which was the source of more hit singles in the Top Ten (seven) than any other record, rock or otherwise, in history. He even trumped that claim to immortality by marrying, briefly, King Elvis’s only child, Lisa Marie Presley, in 1994.

I think it was Greil Marcus who observed that Michael Jackson was a god who became a mere celebrity, and there is a terrible truth to this observation. For the last quarter century of his life—that is, the second half—Michael Jackson’s career seemed like nothing so much as an apocalyptic spiral that served as an illustration of the Platonic allegory of the consequences of the inevitable deviation from the Good. He resembles no rock star so much as Elvis, for reasons, I suspect, that will emerge in those inevitable biographies sure to be published, controversial and otherwise, in the coming years. Who shall be to Michael Jackson what Albert Goldman was to Elvis? Jacksonism’s biggest year, arguably, was 1984, the year during which the tidal wave crested and broke, but by then he could claim a world record no one, not even Elvis or the Beatles, had managed to achieve: he had made one monumental, colossal LP—THRILLER, produced by Quincy Jones—which was the source of more hit singles in the Top Ten (seven) than any other record, rock or otherwise, in history. He even trumped that claim to immortality by marrying, briefly, King Elvis’s only child, Lisa Marie Presley, in 1994.

THRILLER contained “Billie Jean,” a tremendous single and perhaps the best song he ever recorded. Michael Jackson’s future career could be read in that song, not only in its lyrical substance (about the perils of stardom), but in what he did with the song, subsequently transforming it into “You’re a Whole New Generation,” that is, a Pepsi commercial jingle. (He did the same thing with other of his songs as well.) The anger and indignation of “Billie Jean” was transformed into a mere soda pop advertisement, but his legions of fans forgave him—as they always did. For THRILLER sold so many copies in its first year and a half of release that its significance was not only measured in total sales, but in terms of its social impact and in its implications. Elvis and the Beatles did that, too, of course, but the phenomenal popularity of that album even surpassed their vast sales.

Michael Jackson’s fascination with the Peter Pan myth became a well-known and idiosyncratic fact of his biography; he even built Neverland Ranch, a juvenile’s attempt (not a juvenile attempt) to equal Hearst Castle. But since Michael Jackson died a celebrity and not a god, it’s unclear whether Neverland Ranch will be named a National Historic Landmark like Hearst Castle was; it may even be torn down. Nor is it clear whether Neverland will be transformed into the shrine to Jackson that Graceland is to Elvis. While Elvis spent compulsively, lavishly, and extravagantly, he never built a shrine to himself remotely like Neverland: compared to the other homes of the rich and famous, Graceland is a very modest home. Elvis never well understood the American myth that he represented; he wore sideburns, for instance, because he thought they made him look like a truck driver. Michael Jackson, likewise, misread the myths he embodied; while he may have had a fascination with the Peter Pan myth, he didn’t understand the myth very well at all. For Michael Jackson reminds me of no one so much as Tennyson’s Tithonus, the mere mortal who fell in love with Aurora, immortal Goddess of the Dawn. Because he had fallen in love with an immortal goddess, Tithonus asked the gods for Eternal Life. His critical mistake, though, was that he forgot to ask for Eternal Youth: only a fool tries to negotiate with the gods, that is, Fate. Tithonus, as Tennyson tells his story, just grew older and older, more and more decrepit, enjoying the blessings of Eternal Life but not that of Eternal Youth, until he haunted the woods alone, afraid to show himself to other mortals, while his body slowly, but not quite, disintegrated. His blessing was a singular curse, one that no one, not even Peter Pan himself, would ever have to suffer. Even late his career, just before the train was about to run off the tracks, Elvis could laugh, and laugh heartily, perhaps most deeply, at himself. I don’t remember Michael Jackson that way, and perhaps that makes all the difference.

Tuesday, June 23, 2009

Garage

“Garage rock” is meant to invoke a “tradition” in rock music, but it is a tradition that has been created only in retrospect. For it is a fact that no group of amateurs, inspired by the Beatles to pick up a guitar and do covers of British Invasion songs, ever imagined themselves as a “garage band.” The difference between a so-called “garage band” and a “rock band” is that the latter achieved stardom, while the former did not. Limited largely by economics and by technical deficiencies, garage bands never broke free of the local scene, and failed—although not, presumably, by choice. No doubt they would have preferred to have been successful. A local band may have a local hit, but very few local bands are able to transform a local hit into a national hit; there are exceptions to this rule, of course, but as always, the exception proves the rule.

“Garage rock” is meant to invoke a “tradition” in rock music, but it is a tradition that has been created only in retrospect. For it is a fact that no group of amateurs, inspired by the Beatles to pick up a guitar and do covers of British Invasion songs, ever imagined themselves as a “garage band.” The difference between a so-called “garage band” and a “rock band” is that the latter achieved stardom, while the former did not. Limited largely by economics and by technical deficiencies, garage bands never broke free of the local scene, and failed—although not, presumably, by choice. No doubt they would have preferred to have been successful. A local band may have a local hit, but very few local bands are able to transform a local hit into a national hit; there are exceptions to this rule, of course, but as always, the exception proves the rule.

Jack Holzman and Lenny Kaye’s NUGGETS collection, issued in 1972, invented the faux tradition within rock culture named “garage.” What they were really doing was celebrating the abject, that which had been ignored and forgotten. Although that wasn’t its explicit purpose, the NUGGETS anthology served to remind fans of the sacrifices, largely personal, that those who failed made in order to maintain rock music as a significant cultural value. By the mid-1970s, a decade after the Beatles’ annus mirabilis of 1964 and by which time the Beatles no longer existed as a band, the cultural ruin created by the Beatles—rather like a massive tsunami destroys the cities built too close to the shore—could be surveyed, catalogued, and celebrated. NUGGETS did just that. But like any historical reconstruction that attempts to make the past intelligible, such ruins can only be assembled from fragments, which is precisely what the first NUGGETS collection is, an assemblage of abject fragments, of proverbial “diamonds in the rough.” So what, precisely, is meant by “garage”? Michael Hicks conveniently provides us a set of features:

A garage is a rougher, dirtier place than where humans typically reside; a place to store heavy machinery and marginally useful possessions. It is a place of noise of alienation, a psychological space as much as a physical one. In this light “garage band” implies a distancing from more respectable bands (and from more respectable social enterprises in general). The Clash put it well in the chorus to one of their early songs: “We are a garage band/We come from a garage land.” (Sixties Rock: Garage, Psychedelic, and Other Satisfactions, p. 25.)

Garage is perhaps the only “tradition” in rock that is defined strictly by economics and by the professional stature of the band members. But as Hicks reveals, the values celebrated by 1970s punk transformed music that had been marginal in an earlier era into an “authentic” form of rock music in a later one. But if it was so obviously authentic, why had it been marginalized? Collections such as NUGGETS are premised on the assumption that they rescue masterpieces from undeserved neglect, and while that is a powerful myth, it is just that, a myth. The fact that it is just another “sales pitch” goes unremarked. I suppose I’m jaded, because the discourse of popular music has always pitted the “authentic” (The Real) against the “conventional” (The Popular) for the purpose of selling records to a broad (as opposed to a narrow few) audience. It is an old ploy. Listeners are encouraged to find “authenticity” in the marginal (“alternative,” once “underground” rock), the canonical (“classic” rock), or the unfamiliar (e.g., Delta blues). The same holds true for “garage” rock, a faux tradition where listeners are told they may also find the “authentic.” Am I “anti-garage”? Not at all: the NUGGETS collection contains perhaps nine great songs, but what a great nine they are. Not everything is genius, or the word has no meaning. And a great song is a great song, regardless of its putative “tradition.”

Sunday, June 21, 2009

Progressive Rock Redux

I’ve blogged on the subject of so-called “Progressive Rock” (or “Art Rock,” a collocation presumably derived from the phrase “high art,” as in “high art pretensions”) previously, but since yesterday’s entry on Ali Akbar Khan, I’ve been thinking again about the subject. My earlier rumination on the subject of progressive rock argued that its development is inseparable from developments in recording technology, i.e., studio engineering. By the early 1970s (and possibly sooner), the recording engineer began to be listed on an album’s credits right along with band members, suggesting his essential role in the recording process. The trouble with writing about something like prog rock is that the bands normally associated with this kind of music (e.g., King Crimson) were stylistically adventurous, and hence did not consciously identify themselves with one style of music: the term has been applied only retrospectively, in order to explain a certain stylistic direction in rock music that developed during the late 1960s. By way of analogy, think of the history of “Punk Rock.” Punk, as a term used to describe the culture around a type of rock music, had no currency until 1975. Soon after, the word punk gained currency, people identified themselves and their culture with the term and they started piecing together a history, memorializing certain figures that preceded them and ascribing to those figures their own desires, which these predecessors could not have fully known. Thus, some punks memorialized the MC5 and The Stooges, while others memorialized the Velvet Underground, and so on. The point is, historical narratives were formed around punk rock, the function of which was to create predecessors for the music (and hence legitimate it), but these predecessors could not have fully understood the future they supposedly authored.

I’ve blogged on the subject of so-called “Progressive Rock” (or “Art Rock,” a collocation presumably derived from the phrase “high art,” as in “high art pretensions”) previously, but since yesterday’s entry on Ali Akbar Khan, I’ve been thinking again about the subject. My earlier rumination on the subject of progressive rock argued that its development is inseparable from developments in recording technology, i.e., studio engineering. By the early 1970s (and possibly sooner), the recording engineer began to be listed on an album’s credits right along with band members, suggesting his essential role in the recording process. The trouble with writing about something like prog rock is that the bands normally associated with this kind of music (e.g., King Crimson) were stylistically adventurous, and hence did not consciously identify themselves with one style of music: the term has been applied only retrospectively, in order to explain a certain stylistic direction in rock music that developed during the late 1960s. By way of analogy, think of the history of “Punk Rock.” Punk, as a term used to describe the culture around a type of rock music, had no currency until 1975. Soon after, the word punk gained currency, people identified themselves and their culture with the term and they started piecing together a history, memorializing certain figures that preceded them and ascribing to those figures their own desires, which these predecessors could not have fully known. Thus, some punks memorialized the MC5 and The Stooges, while others memorialized the Velvet Underground, and so on. The point is, historical narratives were formed around punk rock, the function of which was to create predecessors for the music (and hence legitimate it), but these predecessors could not have fully understood the future they supposedly authored.

On albums such as RUBBER SOUL (1965) and REVOLVER (1966), which incorporated Eastern music and instruments (the incorporation of novel timbres) uncommon in rock music at the time, the influence of Khan is somewhat easier to trace, although certainly this influence doesn’t explain the actual songs themselves, nor does it explain the use of the symphony orchestra or orchestral instruments, or songs with large sectional forms distinguished by textural contrast between the sections, certain stylistic features of progressive rock. In addition, prog rock characteristically employs what Charlotte Smith calls linear through-composition:

. . . the text is generally divided into short phrases that are introduced and imitated. As each phrase ends in the imitating voice, a new theme is entering in the other voice, overlapping the conclusion of the previous phrase. The overlapping, or dovetailing, technique makes it possible for the melodic flow to continue, as it would not if both voices rested at the same moment. As each theme is imitated, the original text setting is repeated, and the voices, after the imitation is dropped, continue toward a cadence. The same procedure is then repeated for successive phrases, the cadence interrupted each time with the new theme in one voice overlapping the conclusion of the previous phrase in the other voice. This style of through-composition, each interior phrase knit to the preceding phrase, is made more convincing by having the linear emphasis reinforced by the devices of imitation. (A Manual of Sixteenth-Century Contrapuntal Style, pp. 65-66).

My candidate for an excellent (very) early example of this songwriting technique in rock music would be the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations” (October 1966), which also happened to be heavily dependent on studio technology. Certainly “Good Vibrations” qualifies as an instance of prog rock: novel timbres (orchestral instruments; the Theremin), sectional forms distinguished by textual contrast, and linear through-composition (“each interior phrase knit to the preceding phrase,” as well as the way each theme is successively imitated). (Youtube video here.) According to Paul McCartney, the Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “A Day in the Life” (both on SGT. PEPPER’S, June 1967) were inspired by Brian Wilson. And in November 1967, the Moody Blues released DAYS OF FUTURE PASSED, which virtually codified prog rock, particularly with the songs “Tuesday Afternoon” and “Nights in White Satin.” (Given my definition, memorable songs from this period such as Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale” don’t really qualify.) Thus it seems to me to understand thoroughly the stylistic development in rock music known as progressive rock, the late 1966 - late 1967 period is key.

Saturday, June 20, 2009

Ali Akbar Khan, 1922-2009

The Los Angeles Times reported this morning that Ali Akbar Khan, the master Indian musician and composer who was a key figure in introducing the music of India to the United States, has died at age 87. Khan was born 14 April 1922, in Shivpur, East Bengal (now Bangladesh), and began playing the sarod (a 25-stringed instrument that is similar to the Middle Eastern oud) and other instruments as a boy. He became a legendary sarod player and music teacher, but for many his greatest significance was in the popularization of Indian music to the West. Remarkably, he recorded more than 95 albums, was nominated for five Grammy Awards, and composed scores for both Indian and Western films, including Satyajit Ray’s DEVI (1960), Merchant-Ivory’s THE HOUSEHOLDER (1963), and Bernardo Bertolucci’s LITTLE BUDDHA (1993). The L. A. Times obituary said:

The Los Angeles Times reported this morning that Ali Akbar Khan, the master Indian musician and composer who was a key figure in introducing the music of India to the United States, has died at age 87. Khan was born 14 April 1922, in Shivpur, East Bengal (now Bangladesh), and began playing the sarod (a 25-stringed instrument that is similar to the Middle Eastern oud) and other instruments as a boy. He became a legendary sarod player and music teacher, but for many his greatest significance was in the popularization of Indian music to the West. Remarkably, he recorded more than 95 albums, was nominated for five Grammy Awards, and composed scores for both Indian and Western films, including Satyajit Ray’s DEVI (1960), Merchant-Ivory’s THE HOUSEHOLDER (1963), and Bernardo Bertolucci’s LITTLE BUDDHA (1993). The L. A. Times obituary said:

“He was instrumental in transforming Indian music into an international tradition in a way that was unprecedented,” said David Trasoff of Los Angeles, a senior student of Khan’s who has studied north Indian classical music and sarod performance for the last 36 years. “What he attempted to do and, I believe, succeeded in doing was to transplant this very deep musical tradition by committing himself to a level of teaching that resulted in a number of protégés who have gone on to present this music throughout the world,” Trasoff said.

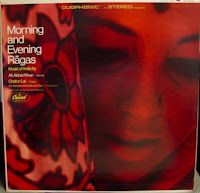

Khan’s earliest record in the West was issued on the Angel label in 1955; Odeon began issuing his records in the early 1960s (available in the U. S. as imports), followed by a series of records issued in the United States by the Connoisseur Society beginning in 1965. Additionally, Khan’s duets with Ravi Shankar were a key factor in introducing the latter musician to rock culture. By the late 1960s, the music of the sarod became frequently associated with the psychedelic experience, that is, with transcendence and transformation, and while Khan recorded very few pieces for films in the West, his influence can be heard, for instance, in soundtracks such as that of Jack Nitzsche’s for PERFORMANCE (1970). As I indicated earlier, Khan recorded many dozens of albums, but here are few of them that had some influence on the rock music of the 1960s:

Morning & Evening Ragas (Angel, 1955)

Music of India (with Ravi Shankar) (Odeon, 1960)

Classical Music of India (Odeon, 1961)

Ali Akbar Khan (Odeon, 1965)

Master Musician of India (Connoisseur Society, 1966)

Predawn to Sunrise Ragas (Connoisseur Society, 1967)

Flowers of Evil: Six Poems By Baudelaire narrated by Yvette Mimieux (Connoisseur Society, 1968)

Shree Rag (Connoisseur Society, 1969) (1970 Grammy Award Nomination)

Concert for Bangla Desh (with Ravi Shankar) (Apple, 1971)

In Concert 1972 (with Ravi Shankar) (Apple, 1972)

Although there many sites on the web featuring Khan playing the sarod, for convenience I've made a link to one of them here.

Tuesday, June 16, 2009

Now In Its 20th Year

Today, over on his WatchBlog, Tim Lucas announced that Donna had informed him VIDEO WATCHDOG has officially entered its twentieth year of publication. Donna remembers receiving the copies of VW #1 from the publisher on June 15, 1990, nineteen years ago yesterday. That bit of news prompted me to think about my and Becky’s long association with the venerable magazine, and I realized that our association with VIDEO WATCHDOG has now entered its twelfth year: our first reviews for the magazine were published in VW #45 (May/June 1998), eleven years ago last month (cover pictured). We have therefore been involved with the ‘DOG for over half of its life. Becky and I have cherished our association with the magazine, primarily because it has been one of the happiest and more fulfilling activities of our professional lives.

Today, over on his WatchBlog, Tim Lucas announced that Donna had informed him VIDEO WATCHDOG has officially entered its twentieth year of publication. Donna remembers receiving the copies of VW #1 from the publisher on June 15, 1990, nineteen years ago yesterday. That bit of news prompted me to think about my and Becky’s long association with the venerable magazine, and I realized that our association with VIDEO WATCHDOG has now entered its twelfth year: our first reviews for the magazine were published in VW #45 (May/June 1998), eleven years ago last month (cover pictured). We have therefore been involved with the ‘DOG for over half of its life. Becky and I have cherished our association with the magazine, primarily because it has been one of the happiest and more fulfilling activities of our professional lives.

I remember sending an email to Tim very early in 1998 saying Becky and I would love the opportunity to review for the magazine, and asking if he would be both interested, and willing, to have us send our reviews of the Criterion Collection laser discs of THE NIGHT PORTER (1974) and VICTIM (1961), issued by Criterion at the same time in December 1997. As I recall, he responded to my email rather quickly, saying sure, he would be happy to consider publishing our reviews of these discs—but they would be considered merely as “spec” reviews, meaning there was no guarantee they would be accepted for publication. I wrote back saying I was delighted that he had agreed to consider reading our reviews, and also that I perfectly well understood that he, as editor, had the right to reject them. But secretly I was very sure he wouldn’t.

And he didn’t. A couple of weeks after I first initiated contact, I sent him our reviews of those discs, and happily, he accepted them for publication, thus beginning our long association with the magazine. In his email accepting them, he asked me if there were any feature articles we might be interested in writing for VW. I wrote back telling him that we would love to write a piece on the EVIL DEAD trilogy, a proposal that he thought was a great idea, and one we later wrote for the magazine. Moreover, given the fact that the “blood red” edition of EVIL DEAD 2 had been recently issued on laser disc, he asked us to review that LD as well. So those three laser discs—the “blood red” LD issue of EVIL DEAD 2: DEAD BY DAWN, THE NIGHT PORTER, and VICTIM, were our first unholy three published in VIDEO WATCHDOG. We still have those laser discs, but they are now, a mere eleven years later, artifacts of a now moribund era of home video. They are not without a little monetary value, of course, especially for collectors, despite being a form of déclassé technology. But I strongly suspect that Becky and I will always hold on to those discs, because they represent our very first association with VIDEO WATCHDOG. I remember times, early on, when the VHS and LD reviewers for VW were Tim, longtime contributor John Charles, Kim Newman, and Becky and me, with Douglas E. Winter doing soundtrack reviews and, as I recall, Anthony Ambrogio writing the book reviews. Soon after, by the next year, I think, Richard Harland Smith had joined on, and The Kennel continued to grow from there. We have learned and profited from the writing of all the contributors to VIDEO WATCHDOG, and are delighted to be among such esteemed company. Through our association with VW, Becky and I were able to meet some people who would later help us considerably with our book on Donald Cammell, including David Del Valle and Brad Stevens. Just a few years ago, I was able to meet Richard Harland Smith in Los Angeles, when he stopped by to see the Drkrm.com exhibition of art from the Corman Poe films that David Del Valle had arranged and curated. Thus, my and Becky’s association with VIDEO WATCHDOG has been to our great professional advantage, among other benefits, including allowing us the opportunity to meet new friends.

We didn’t actually meet Tim and Donna until several years later, in July of 2006, when we swung through Cincinnati on our way back from Montreal, where we’d attended the official North American release of our book, DONALD CAMMELL: A LIFE ON THE WILD SIDE. Accompanied by our young son John, Becky and I enjoyed a memorable evening of laughter and conversation with Tim and Donna, the kind of evening that made me wish we lived closer together, a sentiment that I know Tim has expressed as well. (You can read all about our meeting in his WatchBlog entry of July 17, 2006.) Tim and I are very close to the same age, although I’ve always prided myself in being the oldest (“senior”) member of the current VW Kennel—and how often does a person brag about being older than his peers?

So here’s to you, Tim and Donna, and the first nineteen years of VIDEO WATCHDOG! Becky and I have thoroughly enjoyed our association with you and your venerable magazine, thank you for the opportunities you have given us, and look forward to its continuation as long as you wish to pursue publishing it. We also look forward to spending another evening or two (or ten) of conversation and laughter with you, accompanied by fine food and wine, of course, and the pleasure of the company of friends we just don’t see often enough. Alas. And here’s to all of our fellow Kennel members as well, with whom we’ve often disagreed, but always learned, and been frequently astonished by the range and scope of your erudition.

Friday, June 12, 2009

Take Your Girlie to the Movies

“Take Your Girlie to the Movies” was originally a hit in 1919 by famed vocalist Billy Murray, the most popular male singer in America before Al Jolson. The song reveals how quickly the movie theater became a popular setting for the courtship ritual, and includes references to popular movie stars of the Teens (for instance, Billie Burke, perhaps best known to modern audiences as Glinda, the Good Witch of the North, in The Wizard of Oz), as well as social mores of that earlier era. According to journalist Jim Walsh, Billy Murray sold more records than any other pop singer in America between 1910 and 1920. Prior to the era of the compact disc, Murray’s legacy was kept alive by acoustic era record collectors and students of the early history of the phonograph. They exchanged discs and cylinders as well as dubs on open reel tape and cassettes. Because Murray spent much of his professional time in the studio rather than performing live, his recordings comprise the bulk of his legacy.

“Take Your Girlie to the Movies” was originally a hit in 1919 by famed vocalist Billy Murray, the most popular male singer in America before Al Jolson. The song reveals how quickly the movie theater became a popular setting for the courtship ritual, and includes references to popular movie stars of the Teens (for instance, Billie Burke, perhaps best known to modern audiences as Glinda, the Good Witch of the North, in The Wizard of Oz), as well as social mores of that earlier era. According to journalist Jim Walsh, Billy Murray sold more records than any other pop singer in America between 1910 and 1920. Prior to the era of the compact disc, Murray’s legacy was kept alive by acoustic era record collectors and students of the early history of the phonograph. They exchanged discs and cylinders as well as dubs on open reel tape and cassettes. Because Murray spent much of his professional time in the studio rather than performing live, his recordings comprise the bulk of his legacy.

Murray was an extremely popular singer as early as 1905. By June 1906, Murray’s recording of “The Grand Old Rag” was the biggest-selling record in the Victor Company’s history. Songs recorded by Murray in 1905, such as “In My Merry Oldsmobile” and “Everybody Works But Father,” remained in record catalogs until the early 1920s, suggesting their popularity. In 1909 Murray formed the American Quartet (known as the Premier Quartet on Edison cylinder releases), best known for its interpretations of ragtime and novelty songs. Among the group’s early bestsellers were “Casey Jones,” “It’s A Long, Long Way to Tipperary,” “Moonlight Bay,” and “Oh, You Beautiful Doll.” By the 20s, Murray wasn’t quite as popular as he had been (his “old-fashioned” music was being displaced by jazz), but he still had hits with “(Down by the) O-H-I-O (I’ve Got the Sweetest Little O, My! O!)” (with Victor Roberts), “Strut, Miss Lizzie,” “That Old Gang Of Mine” (with Ed Smalle), and “Don’t Bring Lulu.” The latter song, “Don’t Bring Lulu,” was re-recorded by Kay Kyser’s band in 1935, although the song had been part of his band’s repertoire for at least a year. At the same time, Kyser also recorded Murray’s earlier hit, “Take Your Girlie to the Movies” (Sully Mason, vocal), and likewise had a minor hit from it. Hence from the Teens on, the movies had been a subject of popular music.

A Few Pop Songs Referencing the Movies:

The Beatles – Act Naturally

Jimmy Buffett – Grapefruit Juicy Fruit

Johnny Cash – Ballad of a Teenage Queen

Cher – Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)

Dennis Yost & The Classics Four – Spooky

The Drifters – Kissin’ in the Back Row of the Movies

The Drifters – Saturday Night at the Movies

The Everly Brothers – Wake Up Little Susie

Bertie Higgins – Key Largo

Alan Jackson – Here in the Real World

Kay Kyser and His Orchestra – Take Your Girlie to the Movies

Buck Owens – Act Naturally

Stan Ridgway – Beloved Movie Star

Yes – Cinema

Tuesday, June 9, 2009

Cathedrals Are Not Built By The Sea

I’ve mentioned a few times previously on this blog my customary habit of scouring the bins for used records at my local Goodwill Store. The store is located a mere four blocks from my home, which I suppose encourages my weekly routine, and while I seldom find anything significant, an occasional gem sometimes can be uncovered. I found nothing during my visit today, but I did notice this time that there were an unusually high number of Christian music LPs. These sort of records, many of them pressed by small and obscure labels, can always be found in the bins there, but this time they comprised the majority of the records, and I don’t mean a simple majority, but perhaps comprising two out of three of all the records there (perhaps 70-80 total).

I’ve mentioned a few times previously on this blog my customary habit of scouring the bins for used records at my local Goodwill Store. The store is located a mere four blocks from my home, which I suppose encourages my weekly routine, and while I seldom find anything significant, an occasional gem sometimes can be uncovered. I found nothing during my visit today, but I did notice this time that there were an unusually high number of Christian music LPs. These sort of records, many of them pressed by small and obscure labels, can always be found in the bins there, but this time they comprised the majority of the records, and I don’t mean a simple majority, but perhaps comprising two out of three of all the records there (perhaps 70-80 total).

I’ve noticed this fact for as long as I’ve shopped there. Perhaps the percentage hasn’t been has high as it was today, but these types of records are nonetheless a noticeable and persistent presence in the bins. These Christian records—spoken-word recordings of books of the New Testament, collections of hymns by obscure gospel groups, traditional hymns sung by unfamiliar husband and wife duos (and families), and so on—have always been abundant in the used record bins. Sometimes I’ve found up to eight sealed copies of the same record, as if someone had dumped off the whole pile simply in order to get rid of them. There are more of these records in number than soundtracks to dreary old movies (e.g., Exodus, Dr. Zhivago) and albums by Montovani, Ferrante & Teicher, and The 101 Strings. Far fewer of these latter kinds of records show up than Christian LPs. People don’t seem to want to hold on to their old, once cherished religious records—why?

Elvis, for instance, recorded some great gospel records, but I’ve seldom come across these albums in the used bins. Of course most any record by Elvis is collectible and it is quite likely that some other collector may have grabbed them before I did, but I think the only used gospel record by Elvis I’ve ever come across at the Goodwill store is He Touched Me (1972), but I visually graded it poor, and since I already had an early pressing of the record, I didn’t pick it up. But a gospel record by Elvis is one thing, and a record by an anonymous gospel group consisting of four white nerds garbed in garish polyester is another. If I may speculate, I think these Christian records are dumped by the score at the local Goodwill Store because they just don’t have anything to offer. There’s nothing remotely “inspirational” or aesthetically interesting about them; they are empty signifiers drained of any transcendent meaning. They are dull and uninspiring, eerie and morose, the aural equivalent of a flickering neon cross attached to a rusting metal building alongside the highway.

Or rather, a roadside neon cross on a beautiful, star-filled summer night. The tawdriness of the manufactured symbol is rendered insignificant by the sheer magnificence of the universe itself. The neon symbol says: I’m a cheaply produced, short-lived, and profane object. The night sky says: Behold something greater and more magnificent than yourself. The title for this entry is inspired by a poem by Wallace Stevens:

Cathedrals are not built along the sea;

The tender bells would jangle on the hoar

And iron winds; the graceful turrets roar

With bitter storms the long night angrily;

And through the precious organ pipes would be

A low and constant murmur of the shore

That down those golden shafts would rudely pour

A mighty and a lasting melody.

And those who knelt within the gilded stalls

Would have vast outlook for their weary eyes;

There, they would see high shadows on the walls

From passing vessels in their fall and rise.

Through gaudy widows there would come too soon

The low and splendid rising of the moon.

Stevens suggests that churches aren’t built by the sea because the sound of the sea would overpower any sermon that could possible be recited—the attention of the weary churchgoers would be drawn outside, to the overpowering sound and sight of the sea, not to the paltry words that make up the (familiar) sermon. The wind, the occasional storm, the moonlight, the primordial sound of the waves lapping the shore—all phenomena of the natural world—spiritually satisfy the tired parishioners much better than does the church itself. No wonder the records I saw today are dumped off by the dozen.

Sunday, June 7, 2009

A Dirty Mind Is A Terrible Thing To Waste

It is an error to believe that the Hollywood Production Code prohibited sexual content—it did not. Rather, it simply codified its ciphered expression (e.g., the pan out the window, with the curtain gently flapping in the breeze, to indicate the sex that was about to take place off-camera and out of sight). As Slavoj Zizek has shown, the Hollywood Production Code of the 30s and 40s “was not simply a negative censorship code, but also a positive (productive, as Foucault would have put it) codification and regulation that generated the very excess whose direct depiction it hindered” (The Art of the Ridiculous Sublime, p. 6). Stated in another way, the role of censorship is far more ambiguous than it seems. Prohibition does not simply function in a negative way, but in fact generates the excessive, all-pervasive sexualization of everyday experience. Edgar Allan Poe referred to this unintended by-product of prohibition as “the imp of the perverse,” the obscene underpinning that supports systems of symbolic domination. In other words, prohibition encourages the subject to develop a “dirty little mind”: without the prohibition, the perverse impulse remains dormant, inactive.

It is an error to believe that the Hollywood Production Code prohibited sexual content—it did not. Rather, it simply codified its ciphered expression (e.g., the pan out the window, with the curtain gently flapping in the breeze, to indicate the sex that was about to take place off-camera and out of sight). As Slavoj Zizek has shown, the Hollywood Production Code of the 30s and 40s “was not simply a negative censorship code, but also a positive (productive, as Foucault would have put it) codification and regulation that generated the very excess whose direct depiction it hindered” (The Art of the Ridiculous Sublime, p. 6). Stated in another way, the role of censorship is far more ambiguous than it seems. Prohibition does not simply function in a negative way, but in fact generates the excessive, all-pervasive sexualization of everyday experience. Edgar Allan Poe referred to this unintended by-product of prohibition as “the imp of the perverse,” the obscene underpinning that supports systems of symbolic domination. In other words, prohibition encourages the subject to develop a “dirty little mind”: without the prohibition, the perverse impulse remains dormant, inactive.

Hence the best marketing strategy, the best way to sell something, is to hint at the existence of some transgressive image or form of expression while maintaining a socially acceptable decorum at the same time: you must be able to activate the spectator’s dirty little mind while nonetheless adhering to standards of decency. The asterisk, for instance, is a stigmatic mark that both conceals, and yet signifies, profanity, e. g., in the word mother*****r.  A famous use of the asterisk is in the title of the Rolling Stones song, “Starfucker,” which became “Star Star” on Goat’s Head Soup (1973). In the audio-visual realm, bleeping is to the audio track what the asterisk is to print media: the bleep interferes in the aural reception of the offensive word while also pointing out that it was actually uttered. The bleep and the asterisk (and the “Parental Warning: Explicit Lyrics” sticker) are therefore censoring devices that prompt and encourage in the mind of the subject the very “dirty” thoughts they presumably function to prevent. I suspect that the placing of the “Parental Warning” sticker has had the unintentional effect of selling far more units of a particular album than would have happened without it (yet another instance of what Foucault means by “productive” codification leading to excessive expenditure).

A famous use of the asterisk is in the title of the Rolling Stones song, “Starfucker,” which became “Star Star” on Goat’s Head Soup (1973). In the audio-visual realm, bleeping is to the audio track what the asterisk is to print media: the bleep interferes in the aural reception of the offensive word while also pointing out that it was actually uttered. The bleep and the asterisk (and the “Parental Warning: Explicit Lyrics” sticker) are therefore censoring devices that prompt and encourage in the mind of the subject the very “dirty” thoughts they presumably function to prevent. I suspect that the placing of the “Parental Warning” sticker has had the unintentional effect of selling far more units of a particular album than would have happened without it (yet another instance of what Foucault means by “productive” codification leading to excessive expenditure).

The censorship of rock and rock music began with Elvis, who, famously, in September 1956, was censored when he appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show: when Elvis began to sing and dance to Little Richard’s “Ready Teddy,” the camera moved in so that the television audience saw him only from the waist up. Here are a few other examples in the history of rock:

Jimi Hendrix – Electric Ladyland (1968) (for the album’s U. S. release, the twenty nude women were replaced by a close-up of Hendrix performing live)

John Lennon and Yoko Ono – Unfinished Music No. 1—Two Virgins (1968) (sold in the U. S. in a plain wrapper in order to cover the couple’s full frontal nudity)

Blind Faith – Blind Faith (1969) (for the U. S. release, a nude young girl holding a phallic model airplane was replaced by a picture of the band)

Alice Cooper – Pretties For You (1969) (on some copies a sticker was placed over the drawing of the girl on the right in order to conceal her exposed white panties)

Santana – Abraxas (1970) (cover had a sticker with an excerpt from a review of the band covering the black woman’s exposed genital area)

Alice Cooper – Love It to Death (1971) (RCA record club issue printed only the top half of the front cover, with the bottom half left blank)

Pink Floyd – Wish You Were Here (1975) (early copies of the album in the U. S. were issued with dark blue cellophane in order conceal the cover picture of the man in flames)

Nirvana – Nevermind (1991) (the genitalia of the male baby were airbrushed away)

Chumbawamba – Anarchy (1993) (cover depicting childbirth in close-up was sold in the U. S. in a plain white sleeve)

While Zombie – Supersexy Swingin’ Sounds (1996) (nude girls on the cover and interior booklet are given bikinis in the “clean” version)

Wednesday, June 3, 2009

Rocky Mountain Way

We’re heading off this morning the Rocky Mountain way, planning to spend a couple of days or so with Becky’s niece and her family, who live in an A-frame home 10,000 feet up in the Rocky Mountains. I couldn’t help but think of two of the more famous songs about the Rockies, Joe Walsh’s “Rocky Mountain Way” and (of course) John Denver’s “Rocky Mountain High.” But there’s also Gene Autry’s “Blue Canadian Rockies” (written by Cindy Walker), later covered by The Byrds on Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968), and Lightnin’ Hopkins “Rocky Mountain.” For movies, there’s Errol Flynn’s Rocky Mountain (1950) and the Three Mesquiteers’ Rocky Mountain Rangers (1940), which has absolutely nothing to do with the Rocky Mountains. Likewise, the Randolph Scott western, Rocky Mountain Mystery (1935), has nothing to do with the Rockies as it was filmed in Big Bear Valley, California. At any rate, we’re off for a real Rocky Mountain high, not a stand-in: a little hiking (I’m not up for more than a little), cold, crisp air (and, I hope, cold, crisp beer), a lot of beautiful scenery, and a little sight-seeing. I’m told, since their home is so isolated, to prepare for a brilliant night sky, as the stars at night are something to see. Apparently there will be some requisite Milky Way gazing as well, which is fine with me. Sing it, Joe.

We’re heading off this morning the Rocky Mountain way, planning to spend a couple of days or so with Becky’s niece and her family, who live in an A-frame home 10,000 feet up in the Rocky Mountains. I couldn’t help but think of two of the more famous songs about the Rockies, Joe Walsh’s “Rocky Mountain Way” and (of course) John Denver’s “Rocky Mountain High.” But there’s also Gene Autry’s “Blue Canadian Rockies” (written by Cindy Walker), later covered by The Byrds on Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968), and Lightnin’ Hopkins “Rocky Mountain.” For movies, there’s Errol Flynn’s Rocky Mountain (1950) and the Three Mesquiteers’ Rocky Mountain Rangers (1940), which has absolutely nothing to do with the Rocky Mountains. Likewise, the Randolph Scott western, Rocky Mountain Mystery (1935), has nothing to do with the Rockies as it was filmed in Big Bear Valley, California. At any rate, we’re off for a real Rocky Mountain high, not a stand-in: a little hiking (I’m not up for more than a little), cold, crisp air (and, I hope, cold, crisp beer), a lot of beautiful scenery, and a little sight-seeing. I’m told, since their home is so isolated, to prepare for a brilliant night sky, as the stars at night are something to see. Apparently there will be some requisite Milky Way gazing as well, which is fine with me. Sing it, Joe.

Tuesday, June 2, 2009

Private Parts

Near the end of the half-time show of Super Bowl XXXVIII, Justin Timberlake reached across Janet Jackson’s chest in order to remove a cup from her black leather bustier. In doing so, he happened to reveal her right breast to millions of viewers. Predictably, in the aftermath of the event, many Washington lawmakers invoked the rhetoric of moral outrage. A few months after this particular Super Bowl, Congress approved a measure allowing the FCC to increase the maximum fine from $27,500 to $275,000 for violations of decency on television and radio. In fact, the measure was later inserted into the 2005 defense authorization bill, revealing the control of televised images is on par with national security.

Near the end of the half-time show of Super Bowl XXXVIII, Justin Timberlake reached across Janet Jackson’s chest in order to remove a cup from her black leather bustier. In doing so, he happened to reveal her right breast to millions of viewers. Predictably, in the aftermath of the event, many Washington lawmakers invoked the rhetoric of moral outrage. A few months after this particular Super Bowl, Congress approved a measure allowing the FCC to increase the maximum fine from $27,500 to $275,000 for violations of decency on television and radio. In fact, the measure was later inserted into the 2005 defense authorization bill, revealing the control of televised images is on par with national security.

In a world in which decorum is the only morality left, the exposure of Janet Jackson’s breast on national television was a fundamental breach of etiquette. American culture obviously believes the censorship of body parts is a deep, fundamental value worth preserving at any cost. If a black woman’s breast (don’t they always come in pairs?) can be revealed to millions on national television, what could be next? It would seem the proper covering of body parts is as equally important as national security. However, just so the point can’t be conveniently neglected, Jackson’s breast was not totally exposed—she was wearing a nipple shield big enough to cover completely the areola. This curious fact led many conspiracy-minded critics to conclude that the event was not accidental but a tasteless stunt, engineered to revitalize the aging pop star’s fading career.

The Timberlake-Jackson event is yet another instance of the problematic nature of pop music in American society: inevitably, it would seem, pop music generates controversy. In any case, censorship and proscription lead to counter-strategies and evasive tactics, among them being the use of slang and euphemism, as the lyrics to many pop songs, so linked to vernacular expression, attest. As might be expected, sex organs are highly fetishized body parts in pop lyrics, but so too are breasts, legs, and gluteal muscles. But where’s William Burroughs when you need him? I know of no pop song featuring a Talking Asshole.

Infernal Organs And Body Parts:

Chuck Berry – My Ding-A-Ling

The Black Eyed Peas – My Humps

Jackson Browne – Red Neck Friend

The Commodores – Brick House

Sheena Easton – Sugar Walls

Peter Gabriel – Sledgehammer

Iggy Pop – Cock In My Pocket

K.C. and the Sunshine Band – (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty

Led Zeppelin – The Lemon Song

LL Cool J – Big Ole Butt

Mojo Nixon – Stuffin’ Martha’s Muffin

Primus – Winona’s Big Brown Beaver

Reverend Horton Heat – Wiggle Stick

Salt-N-Pepa – Shoop

Bob Seger – Night Moves

Rod Stewart – Hot Legs

Wreckx-N-Effect – Rump Shaker

Frank Zappa – G-Spot Tornado

ZZ Top – Tube Steak Boogie

Monday, June 1, 2009

“More Popular That Jesus”

The way the story goes, John Lennon’s infamous remark about the Beatles being “more popular than Jesus” was printed in an interview that appeared in the London Evening Standard in early March 1966. Lennon is quoted as saying, “Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue with that; I’m right and I will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first—rock ‘n ‘ roll or Christianity.” Apparently, so the story goes, his remark created nary a stir in Britain upon the publication of the interview.

The way the story goes, John Lennon’s infamous remark about the Beatles being “more popular than Jesus” was printed in an interview that appeared in the London Evening Standard in early March 1966. Lennon is quoted as saying, “Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue with that; I’m right and I will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first—rock ‘n ‘ roll or Christianity.” Apparently, so the story goes, his remark created nary a stir in Britain upon the publication of the interview.

Things went differently in the United States. Roughly five months after the aforementioned interview was published in England, some of Lennon’s remarks from the earlier interview were excerpted and reprinted in the 29 July 1966 issue of Datebook, a teen magazine, apparently to coincide with the release of Revolver on August 8. Within days of the magazine’s appearance on the newsstands, the American backlash against the Beatles began. It took a few days for the remark to circulate in the media, of course, but by 11 August, or right around that date, rock music, at the very least an annoyance, became a full-blown “social problem.” The vast popularity of the Beatles led many adults to conclude that the band’s influence on teenagers was immense, on the assumption, I suppose, that young people would accept their messages uncritically, the personal beliefs of the Beatles being like scripture. The first edition of Bob Larson’s Rock & Roll: The Devil’s Diversion, the subject of which he called “the moral and religious significance of rock and roll music,” was published in January or February of 1967, that is, about five months after Lennon’s remark was reprinted in Datebook. A second edition of Larson’s book followed in 1968, and a third in 1970. However, in a footnote in the third edition (1970) of his book, Larson claims that Lennon’s remark, “Christianity will go. We’re more popular than Jesus now,” appeared in the 21 March 1966 issue of Newsweek. I haven’t confirmed that reference, but I’ll take his word for it. If so, one wonders why the remark didn’t prompt such controversy in the American media until it was reprinted in Datebook in July later in the year.

Peter Watkins’ film Privilege (1967), about the trials and travails of an influential British pop star, was probably being filmed when Lennon’s remark was first published in Britain. But Lennon’s remark, “We’re more popular than Jesus,” was re-deployed and spoken by a character in AIP’s Wild in the Streets (1968), a satirical allegorical fantasy about the political dangers posed by a charismatic rock star. Written by Robert Thom (Death Race 2000, 1975), the film draws on a wide variety of themes, including, perhaps most importantly, the Oedipal romance. It features a weak father (Bert Freed) and a terrible (castrating) mother (Shelley Winters). The mother’s character was probably inspired by the Angela Lansbury figure of 1962’s The Manchurian Candidate, and like the Angela Lansbury character, the Shelley Winters character is shown to be politically ambitious once she learns that her runaway son has become rich and famous. The film’s anti-hero is Max Frost (born Max Flatow, Jr.), played by Christopher Jones, whose lack of proper maternal love is the implied motivation for his desperate need for adulation and affection. Precociously intelligent but also highly self-centered, Max escapes his unhappy home life to become a multi-millionaire by age twenty-two, by forming a hugely successful rock band and by hiring a fifteen-year-old financial genius as a band member. In order to suggest his fundamental immorality, we learn that Max has fathered several illegitimate children with whom he has no contact, literally and emotionally neglecting them in the same way his mother did him. Oddly, he likes to sleep with children, and encourages his band members to use LSD. He does nothing to discourage being seen as a Christ-like figure; in one scene, his hook-handed and slightly stoned band member, played by Larry Bishop, asks Max if he has the power to restore his missing hand.

After learning that 52% of the U. S. population is under twenty-five, Max uses his celebrity status to hijack the proceedings at the youth-oriented political rally of Senatorial candidate Johnny Fergus (Hal Holbrook, sharing a family resemblance to John F. Kennedy, in the same way that Millie Perkins, who plays Fergus’s wife, is meant to suggest Jackie Kennedy). Revealing that he is fundamentally a demagogue rather than an entertainer, Max presents a platform to reduce the voting age in the United States to fourteen (“Fourteen or Fight”) and initiates a covert plan to gain control of the Senate, first by engineering the successful Senatorial bid of drug-addled band member Sally LeRoy (Diane Varsi). Eventually, by lowering the voting age, he is elected President of the United States. In his Oedipal struggle for control over his figurative father, Johnny Fergus, Max lures away Fergus’s son Jimmy (Michael Margotta), “brainwashing” him to his way of thinking and turning him against his parents. Throughout, during his speeches Max has called his youthful minions “troops” and “babies,” and once he is President, he enacts laws imprisoning those over thirty, requiring them to ingest large quantities of LSD. Not only does the film want to suggest the demagoguery of rock stars, but American youth are shown to be terribly misguided, mindlessly throwing support behind an individual who is fundamentally a self-serving tyrant, able to use the power of the media to shape his image for his own ends. The film also invokes the hippie hysteria of the late Sixties, an hysteria that was in part spurred by the counterculture’s embrace of non-Christian (largely Oriental) religion. I suspect that one of the sources of inspiration for Robert Thom’s script was the “CBS Reports” documentary hosted by Harry Reasoner, titled The Hippie Temptation, that aired on 22 August 1967. Indeed, in general the film seems heavily influenced by the media depiction of the counterculture in the late 1960s. The film is one instance of the widespread reaction to Lennon’s remark, and perhaps one of the earliest films to do so.