The shift from the single to the album in the 1950s and 1960s represented a shift from music for dancing to music for listening. As a result, the album, designed for listening, became the basic material artifact of rock culture. (It's no coincidence that the music most strongly associated with the Sixties, psychedelia, was designed for listening on stereo systems.) One consequence of this shift in patterns of music consumption was the rise of the rock critic. Nowadays, of course, rock critics are ubiquitous, but back in those days, there were very few. As an illustration of the rise of rock music criticism, consider the number of journals that were established in the late 1960s:

Crawdaddy! - February 1966

Rolling Stone - November 1967

Creem - February 1969

The problem, though, was that while rock criticism rather quickly became a recognized profession, what was the rock music critic's precise function? Was he simply a means to free promotion and publicity, or did he provide good and true insights into the music? If the latter, what were the criteria for judgement? The rock critic also had an additional problem: If he wanted to be read, he had to have the proper bohemian credentials (a member of the counterculture, or at least sympathetic to it), and therefore to the Left politically. Criticism thus became oppositional, as critics saw their primary function as counteracting commercialism ("hype"), the dominant discourse of the popular press. But how was the critic to go about recognizing The Real Thing? The approach developed at the time was to distinguish the authentic from the commercial, with the idea of authenticity determined negatively, that is, structured by what it was not: for example, Rock was not Pop, Soul was not White. Thus was established the fundamental myth of rock criticism: authenticity vs. commercialism.

That's not all. Like any cultural critic since the time of Matthew Arnold, the critic's authority was premised on his having a keener judgement (in this case, a more discerning ear) than the broader, untrained population. In a way, the critic was the ideal listener, presumably in full position of rock's history: its major figures, moments, themes, contours, its codes, paradigmatic shifts, and its innovators. But how did the critic rescue or recover those albums released prior to the formation of rock criticism in 1966-67? Retroactively, of course, by means of the list, an old Victorian parlor game used to pass the idle hours.

In his Divine Comedy, Dante assigned the virtuous pagans (such as Homer and Virgil) to Limbo, denying them access to salvation because they did not have knowledge of Christ. By way of analogy, we might call Limbo Rock (with all due respect to Chubby Checker) those unaccountably neglected, but nonetheless historically important, albums released prior to the establishment of journals publishing rock criticism such as Rolling Stone in 1967.

Consider Rolling Stone's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. The list is heavily composed of albums released after 1967 A.C. (After Critics). Of course, a few towering figures make the list, those whose B.C. (Before Critics) musical careers could not be ignored--for instance, Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Hank Williams, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, and James Brown--but also, improbably, Phil Spector, who wasn't known as a musician, and John Coltrane, whose 1964 classic jazz album A Love Supreme is in this context (re)considered as a monumental rock album, revealing how fluid and open-ended the category "rock" actually is. Moreover, several of the putative "albums" appearing on the Rolling Stone All-Time list are really singles compilations, assembled on CD decades after the fact, such as Spector's Back to Mono (1958-1969), released in 1991, and Hank Williams' 40 Greatest Hits, released in 1988.

Consider Rolling Stone's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. The list is heavily composed of albums released after 1967 A.C. (After Critics). Of course, a few towering figures make the list, those whose B.C. (Before Critics) musical careers could not be ignored--for instance, Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Hank Williams, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, and James Brown--but also, improbably, Phil Spector, who wasn't known as a musician, and John Coltrane, whose 1964 classic jazz album A Love Supreme is in this context (re)considered as a monumental rock album, revealing how fluid and open-ended the category "rock" actually is. Moreover, several of the putative "albums" appearing on the Rolling Stone All-Time list are really singles compilations, assembled on CD decades after the fact, such as Spector's Back to Mono (1958-1969), released in 1991, and Hank Williams' 40 Greatest Hits, released in 1988.

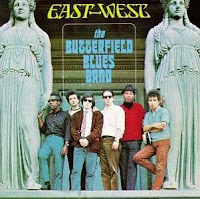

As an example of a profoundly important album not appearing on this list and hence doomed to exist as Limbo Rock, consider the Butterfield Blues Band's East-West, released in August 1966 B.C. (True, it was released a few months after Paul Williams established Crawdaddy! However, at the time, Crawdaddy! was still in limited circulation to college students in mimeographed format.) I fully recognize that the Rolling Stone list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time includes (at #468) the Paul Butterfield Blues Band's eponymous first album, but it is included for entirely the wrong reasons, among them the utterly facile claim that "white kids got the notion they could play the blues." (Underlying this assertion, of course, is the idea of authenticity, that only black men can play authentic blues. Apparently the editors haven't yet read Chapter 3, "Mastering the Cult of Authenticity: Leonard Chess, Willie Dixon, and the Strange Career of Muddy Waters," in Benjamin Filene's essential critical work published in 2000, Romancing the Folk: Public Memory & American Roots Music.) Dave Marsh claims that "East-West can be heard as part of what sparked the West Coast's rock revolution, in which such song structures with extended improvisatory passages became a commonplace." Hence, if importance is measured by influence, as on the Rolling Stone list, then East-West is certainly that. Additionally, according to Mark Naftalin, a member of the Butterfield Blues Band when East-West was recorded, the album's signature piece, "East-West," "was an exploration of music that moved modally, rather than through chord changes." Naftalin goes on to explain:

This song was based, like Indian music, on a drone. In Western musical terms, it "stayed on the one." The song was tethered to a four-beat bass pattern and structured as a series of sections, each with a different mood, mode and color, always underscored by the drummer, who contributed not only the rhythmic feel but much in the way of tonal shading, using mallets as well as sticks on the various drums and the different regions of the cymbals. In addition to playing beautiful solos, Paul [Butterfield] played important, unifying things in the background--chords, melodies, counterpoints, counter-rhythms. This was a group improvisation. In its fullest form it lasted more than an hour."

While the editors of the 500 Greatest Albums list include Miles Davis' Kind of Blue (1959), championing it because Miles Davis turned his back "on standard chord progressions" and for using "modal scales as a starting point for composition and improvisation," they ignore "East-West" for doing the same thing in a rock context. West Coast bands such as Jefferson Airplane are included on the list (Surrealistic Pillow is listed at #146), as is Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young's Déja vu (listed at #147). Still, the album which provided the sonic foundation for much of West Coast rock's success is omitted.

For Dante, those in Limbo do not suffer. However, they endure an even worse fate, to "live in desire without hope." So, too, with those works considered Limbo Rock, recognized by some, but without any hope of canonization.

While the editors of the 500 Greatest Albums list include Miles Davis' Kind of Blue (1959), championing it because Miles Davis turned his back "on standard chord progressions" and for using "modal scales as a starting point for composition and improvisation," they ignore "East-West" for doing the same thing in a rock context. West Coast bands such as Jefferson Airplane are included on the list (Surrealistic Pillow is listed at #146), as is Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young's Déja vu (listed at #147). Still, the album which provided the sonic foundation for much of West Coast rock's success is omitted.